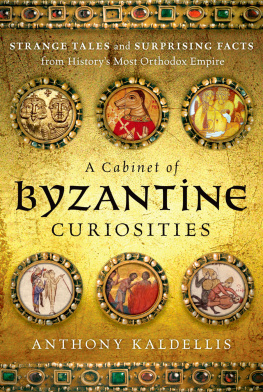

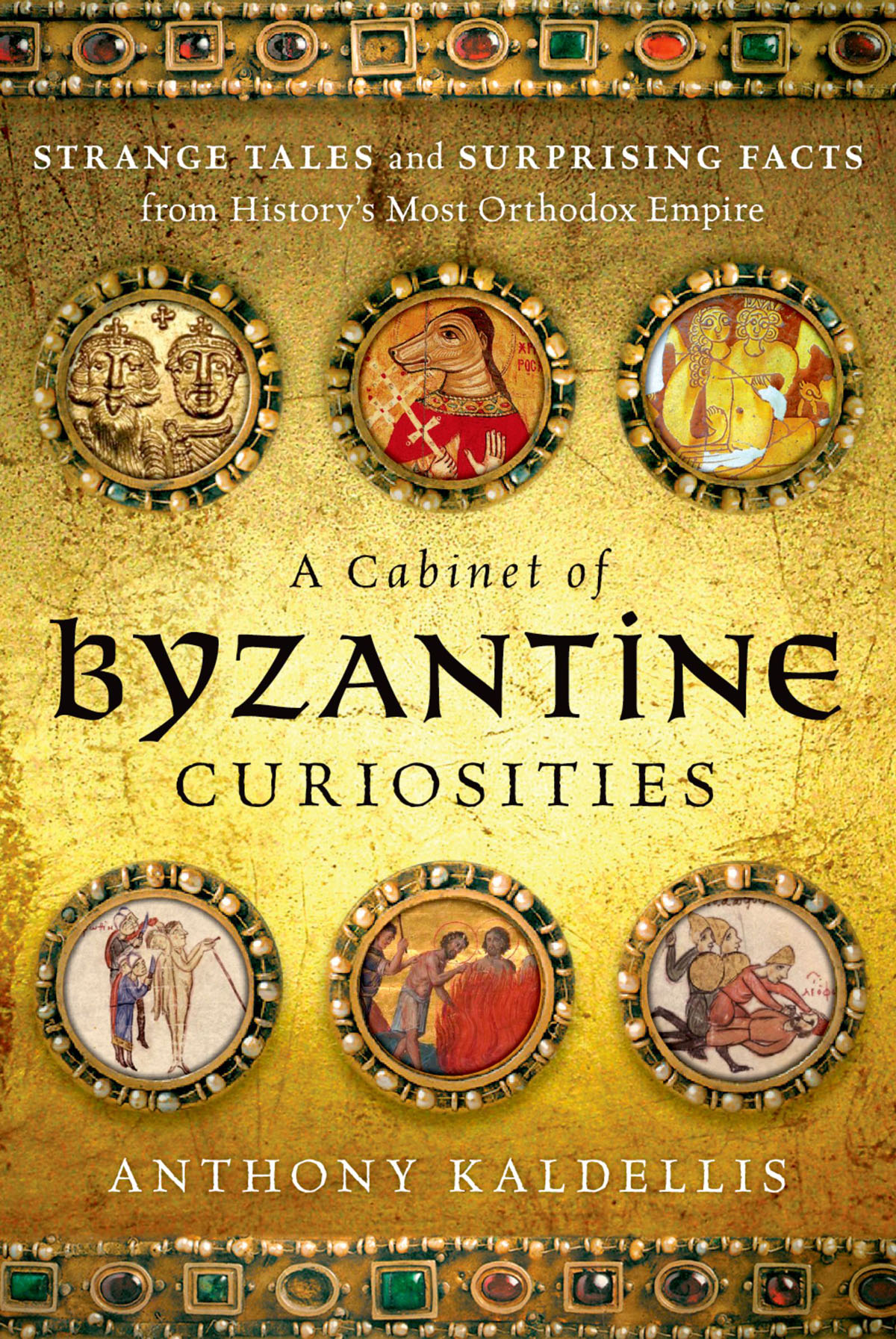

A CABINET

OF

BYZANTINE CURIOSITIES

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kaldellis, Anthony, author.

Title: A cabinet of Byzantine curiosities : strange tales and surprising

facts from historys most orthodox empire / Anthony Kaldellis.

Description: Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2017. |

Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017018263 | ISBN 9780190625948 (hardback) |

ISBN 9780190625955 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190625962 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Byzantine EmpireSocial life and customs. | Byzantine

EmpireSocial conditions. | Byzantine EmpireForeign relations. |

Orthodox Eastern ChurchChurch history.

Classification: LCC DF521 .K295 2017 | DDC 949.5/02dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017018263

For Carolina,

ilusionadamente

CONTENTS

For those who want to lecture or write, this book is not without its uses.

Photios, Ten Thousand Books cod. 167

B YZANTIUM is enigmatic enough by itself, but its popular reputation these days is also a mystery. Undergraduate students at my Midwestern university enroll by the hundreds in introductory survey courses of its history and even attend academic lectures whose Byzantine-themed titles should give them ample warning to stay away. Still, they come. Why? Twenty-year-olds are more opaque to me than Byzantines who lived a thousand years ago. If their interest has deeper roots than the orientalist fantasy of Assassins Creed, I do not know what they are. On the first day of class, they often cannot name a single Byzantine emperor between Constantine I and Constantine XI (which should not be that difficult, when they are asked it that way). In more literate circles, including the mainstream media, Byzantine continues to be used in its pejorative sense, for unnecessarily complicated systems that work through intrigue, evasion of responsibility, obfuscation, and backstabbing. This usage results from centuries of Western prejudice.

In the Western Middle Ages, some Germanic warlords began to fancy themselves as Roman emperors and decided that the Byzantines were not really Romans, as they claimed, but something far, far worse: Greeks, an effeminate, cowardly, and treacherous lot, who ate with forks and liked to read and write. Later, some Catholics decided that the Greek Church was disobedient, even heretical, faithless, and in league with Islam. They ratcheted up the rhetoric. The Byzantine imperial mystique was dispelled when Constantinople was captured by the armies of the Fourth Crusade, in 1204, and then again by the Turks in 1453. In the eighteenth century, Enlightenment thinkers decided to make this long-extinct civilization their poster child for the worst imaginable society: theocratic, superstitious, and run by eunuchs and evil monks with no trace of civic virtue. Voltaire called it a worthless collection of miracles, a disgrace for the human mind, while for Hegel it was a disgusting picture of imbecility; wretched, insane passions stifle the growth of all that is noble. In the twentieth century, some political scientists attributed the totalitarian evils and dysfunctions of the Soviet Union to its Byzantine origins.

The move to rehabilitate this relatively harmless civilization began in earnest quite lateonly in the past generation. Yet despite hopeful claims that the nonsense is all behind us, in reality it continues to shape how Byzantium is discussed. Moreover, it is unclear what positive image has taken its place. Byzantine literature remains mostly inaccessible to the broader public, despite (or because of) the increasing sophistication of studies devoted to it. Byzantine art remains a strong draw, but is often promoted in a way that reinforces the orientalist image of an otherworldly spiritual civilization, and so still caters to Western anxieties and needs. And beyond literature and art, how might Byzantine history and politics find a voice in contemporary discussions and debates? What is Byzantium saying about itself these days?

This conundrum makes it trickier to identify what is strange and surprising about Byzantium. By what standard of normalcy? Greece and Rome have established and relatively coherent reputations to poke fun at. A scientific breakthrough is more curious in a Byzantine context than a Greek one, and, given the Byzantine reputation for mysticism, asceticism, and spirituality, so is the lewd, bawdy, indulgent, and forgiving attitude toward the body that we encounter in so many aspects of Byzantine life. Therefore, a flexible approach seemed best for this volume. I have included material that makes the Byzantines seem weird and alien along with material that highlights their down-to-earth, pragmatic, inventive, and rational sides. They could be a vulgar, worldly, and witty lot, even in their spiritual moments. They had admirable powers of description, a love of paradox, and a deep humanity that was independent of dogma.

A Cabinet of Byzantine Curiosities is primarily a work of entertainment. Each item is self-contained, so the whole can be read in snatches. My highest ambition, that the book should be ideal for bathroom reading, was driven home by the fact that the Greek derivative of French cabinet (kabins) means a toilet.

In another sense, I have written this book as a tribute to those Byzantine authors who have given me so much enjoyment and intellectual stimulation during the past decades. It would include, for example, the philosopher-monk who admitted in a letter to a love-sick friend that I too have fallen for the charms of a brown-eyed girl, and, elsewhere, that I saw a wonderfully-made icon in a church, and so I stole it, by hiding it under my cloak. I can only hope that such Byzantines would appreciate what I have done here under their names. Their culture, after all, produced many thematic anthologies, paradoxography, and collections of edifying tales and miracles, along with books of quotations. They might recognize this book as kindred to one of their own. They did, after all, produce almost all the material that it contains.

OF

OF