Contents

Page List

Guide

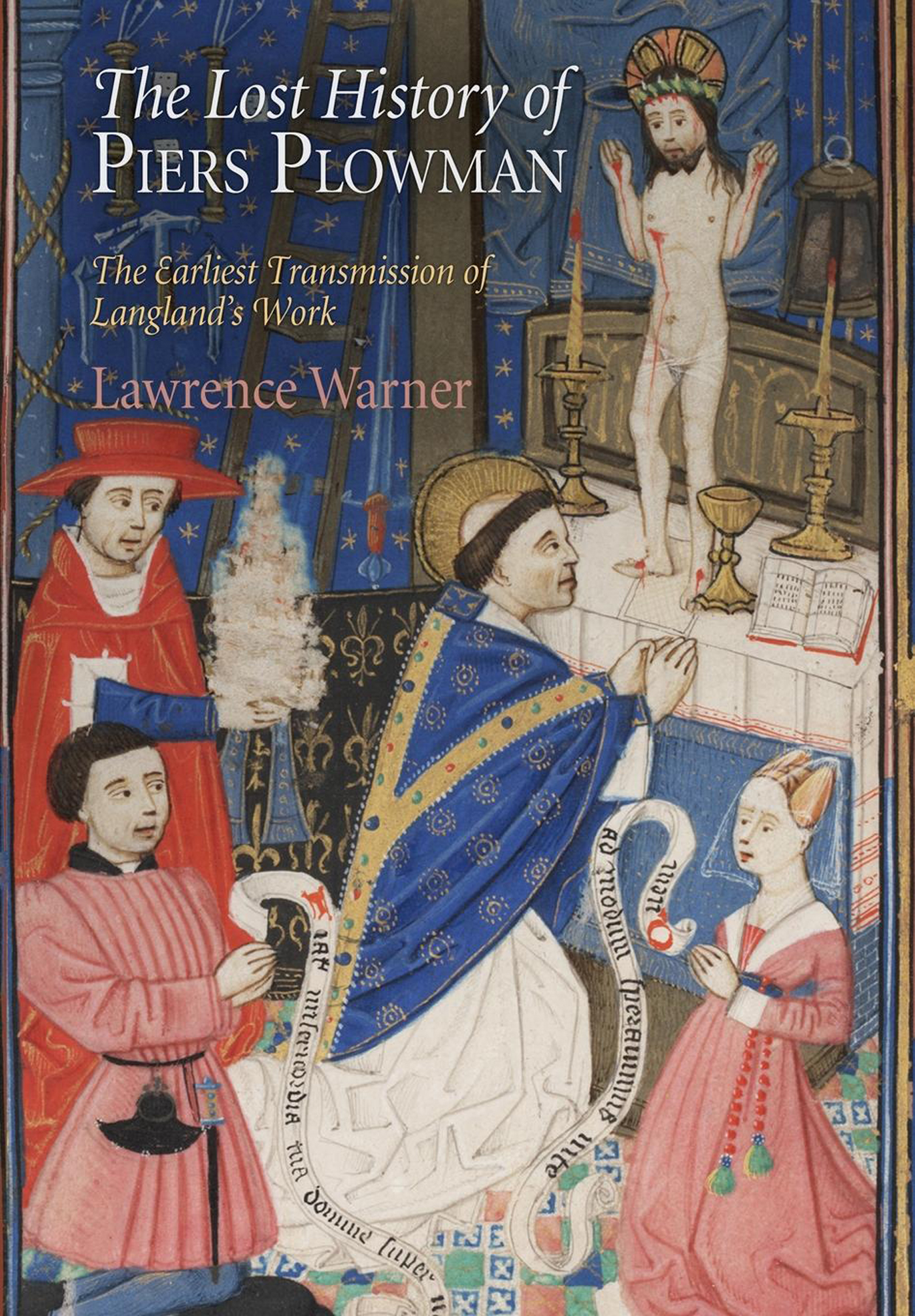

The Lost History of Piers Plowman

THE MIDDLE AGES SERIES

Ruth Mazo Karras, Series Editor

Edward Peters, Founding Editor

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

The Lost History of Piers Plowman

The Earliest Transmission of Langlands Work

Lawrence Warner

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA OXFORD

Copyright 2011 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 191044112

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Warner, Lawrence, 1968

The lost history of Piers Plowman / Lawrence Warner.

p.cm. (The Middle ages series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4275-1 (hardcover; alk. paper)

1. Langland, William, 1330?1400? Piers PlowmanCriticism, Textual. 2. Langland, William, 1330?1400?Manuscripts. I. Title.

PR2016.W37 2010

For Genevieve, with all my love

Contents

Preface

Any history of Langland studies must for the most part tell the history of its textual controversies. Is Piers Plowman the work of one, or of five? How much emendation of the B archetype is justifiable? Is the Z text authorial, or scribal? Has the power of the alphabet blinded us to the true order in which the versions of the poem were composed? What is the value of John Buts testimony, in A 12, to William Langlands poetic career? Middle English scholars are intimately familiar with such questions, because they are so important in defining, not to mention interpreting, Piers Plowman. But a problem I take to be more important than any of these has barely registered in critical consciousness. It is deceptively simple: what is the date of the archetypal B manuscript? On its face the question might seem unduly technical and particular. Surely the real issue is when Langland had completed the B versionthat, at least, is what critics have focused on in attempting to determine the relation between Piers Plowman and, say, the Rising of 1381, or the ideas of John Wyclif. Most if not all offer 137778 as the date of that event. did not use Bx as an exemplar till, say, 1393, then the history of Piers Plowman needs to be rewritten, beginning to end. It would be difficult to maintain, for instance, that the C version was prompted by the publics reception of B, or that John Ball or Geoffrey Chaucer knew the B version by 1381, to take two major cases.

There are good reasons to pursue this possibility. One of those reasons inheres in the elegant program of textual affiliations, over the course of entire passages of up to forty lines long, between a C-character manuscript and the W~M group where the RF group has nothing or is spurious. Much of this book will present and analyze that and related programs, arguing that they are the result of contamination of Bx by the C text as now attested only in Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales MS 733B, a witness to the earliest stage of Piers Plowman C (sigil N2). No one has noticed this because the evidence, which can be presented in relatively simple charts, is dispersed over hundreds of lemmata spread over the three Athlone editions and thus published over a span of some thirty-eight years. Previous assumptions that nothing like this could have occurred had the effect of burying the evidence that undermines those very assumptions. But we do not need to go through all that material to assess the plausibility of the idea that Bx was contaminated by Cindeed, to see that it is likely, perhaps even as certain as the evidence will permit. This instance, while not nearly as complicated as the indications upon which this book focuses, has likewise flown entirely below critics radar, the reasons for which are as important as the indications themselves. The next few paragraphs will thus not only establish some important groundwork for my argument as a whole, but also serve as a miniature copy of that argument and of the phenomena that have rendered it so contrarian.

Both the local and large-scale cases reveal themselves upon examination of small items that just do not fit the usual narratives of Piers Plowmans production. We need to put on our Sherlock Holmes hats to figure them out. The clues to the local mystery did not become apparent until J. A. Burrows 2007 essay on the rubrics of the B-version manuscripts, in which, somewhat hidden beneath all the data presented there, we find this little gem: MS R lacks the whole of Passus XIX and the beginning of XX, but at the end of XX R has Passus iius de do best. Remarkably, L has the same heading (but in its guide only) also at the end of the poem, suggesting perhaps expectation of a further, twenty-first passus. Agreement between L and R here may imply that this anomalous heading was present in the B archetype.

But Burrow omits to mention a crucial piece of information that would have answered the question of how this bizarre rubric got into Bx in the first place: Almost certainly it was laterally imported, perhaps into an ancestor of R, wrote Adams, from a C manuscript (where an identical rubric occurs in the XU family at the beginning of the final passus and a very similar one at the end of the same passus in the majority of all C manuscripts). In light of his later work and the newly apparent presence of MS L in the picture, we need now to substitute into Bx for Adamss perhaps into an ancestor of R. The B archetype, in sum, was contaminated by the C tradition. Any other explanation for LRs agreement in this error would have an extraordinarily difficult row to hoe.

This conclusion incidentally undermines the argument in whose service Burrow had mentioned it, for if the earliest possible stage of the B-tradition rubrics took shape under the influence of the C tradition, and was erroneous at that, it becomes quite difficult to argue for their authorial nature except on purely literary grounds (and in fact only Burrow and, more recently, Hanna have attempted to do so). This should immediately prompt us to wonder, for instance, whether this mistaken rubric was the only item that came into B from the C tradition: might, say, the entire final two passus have been part of this contamination? And to what extent should we assent to the editorial assumption that this could not have occurred?

The Lost History of Piers Plowman follows up on these questions, answering with a resounding yes and not at all respectively. It has two major aims: to lay out the evidence leading to this conclusion, which is far more extensive than what is found in LRs final rubric, and to show that the previous silence about that possibility is not an index to its plausibility, but, rather, the product of the assumption that B was integral. That the only information regarding the LR situation offered by the Kane-Donaldson and Schmidt editions is that MS R has a distinctive rubric on its final folionothing about what the rubric says, or Ls roleshows that we need to go beyond their analyses and methodologies as we assess the earliest production and transmission of the poem. examines in some detail the claims made in the service of the beliefs that B was widely available by c. 1380 and its converse, that