Acknowledgments

EVERY BOOK IS THE PRODUCT of an immense effort. This book would never have been begun, and could not have been completed, without the support, encouragement, and involvement of many people.

I owe an immense debt to my (now former) colleagues at Xerox PARC, with whom and from whom I learned so much about documents, work practice and life. Brian Smith, Geoff Nunberg, Lucy Suchman, John Seely Brown, Dan Brotsky, Cathy Marshall, Richard Southall, and Ken Olson were wonderful co-conspirators in the quest to make sense of documents. The members of the Work Practice and Technology Area (WPT) Jeanette Blomberg, Gitti Jordan, Susan Newman, Julian Orr, Lucy Suchman, and Randy Trigg gently tutored me in matters anthropological and taught me how a research group could operate democratically and compassionately

Thanks too to the many people who read portions of this manuscript in various stages of its development: Allyson Carlyle, Ewan Clayton, Paul Duguid, Margaret Hedstrom, Carl Lagoze, Marc Lesser, Cathy Marshall, Andreas Paepcke, Richard Southall, Lucy Suchman, Nancy Van House, David Weinberger, Zari Weiss, and Alice Wilder-Hall (who also provided editorial assistance).

Many thanks to my agent, Eileen Cope, for her encouragement and tireless efforts; to my editor and publisher, Dick Seaver, for his patient and gentle stewardship; to Greg Comer for his patience and meticulous attention to detail; and to Peter Finkelstein, Jack Lawrence, Jim Neafsey and Paul Roy for their masterful coaching.

I must also thank the two institutions that supported me during the researching and writing of this book: Xerox PARC and the Information School of the University of Washington. I am grateful to John Seely Brown (former director of PARC) and to Mike Eisenberg (dean of the Information School) for providing the space, literally and figuratively, in which the work could be done.

Finally, I have no adequate words to thank two people Ewan Clayton and Zari Weiss for their efforts in support of this book and their contributions to it. If selfless giving is a condition of entry into the world to come, they are both assured palaces in heaven.

1

Meditation on a Receipt

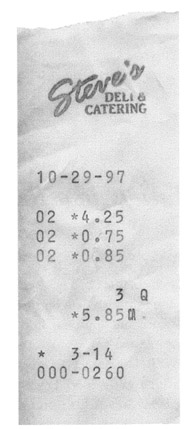

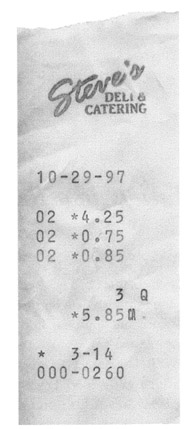

WHAT CAN DOCUMENTS TEACH US? Lets begin by looking at one, close up. The one I have in mind is a cash register receipt, a small strip of paper, 1% inches in width and approximately 4 inches in length, marked in light blue ink. At the top it reads Steves Deli & Catering. Immediately below is a sequence of numbers, 10-29-97, and near the bottom is a decimal value, 5.85. From the look of it, someone bought something from Steves Deli on October 29, 1997, and paid $5.85 for it.

This might seem like an odd place to begin a discussion of documents. Why not begin with a more magnificent specimen, perhaps something beautiful, such as the Book of Kells? Or something more reverently ancient, a Sumerian clay tablet or the Rosetta stone? Or something with an aura of power about it, the U.S. Constitution or an international treaty? This little receipt is so plain and ordinary, so manifestly uninteresting. There are millions and billions of receipts just like it. Every financial transaction at the supermarket, the newsstand, the florist, the drugstore, produces one. You can see peoples attitude toward them in the way theyre handled. They are often left on the counter refused or even handed back with a vague air of displeasure. (I cant be bothered with this.) Or they are stuck away in a grocery bag or stuffed in ones pocket or purse, only to be discarded later. Surely receipts like this are the bottom of the bin.

A receipt for the purchase of a tuna-fish sandwich, a bag of chips, and a bottle of water

But this is exactly the point. If we are going to see into the nature of documents, we would do well to deal directly with the most abundant and ordinary of them. It is easy enough to be transported to heights of ecstasy by the most magnificent specimens. Indeed, we may be spellbound by their beauty and power. The bigger challenge is to look closely and respectfully at the lowest and homeliest of them. And should we find beauty, depth, and power in these, we will surely have accomplished something.

This little receipt is a historical document. Although hardly of the magnitude or the permanence of the Rosetta stone, it is a snapshot of something that happened at another time and place. Embedded in it physically, through the absorption of blue dye into processed tree pulp, is the record of a moment when someone (in fact it was me) bought a tuna sandwich, a bag of chips, and a bottle of water in a deli on El Camino Real in Burlingame, California.

The receipt is historical in another sense as well. If it serves as a reminder of a minor transaction in late October 1997, it simultaneously carries within its form the memory of thousands of years of human struggle and development. That receipts like this one are so readily printed and so casually tossed away is due in large measure to the availability of cheap, high-quality paper. This wasnt always so.

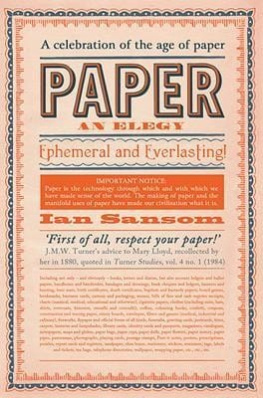

Paper was invented in China in the second century c.e. and made its way to Europe in the twelfth century, carried by Arab traders. We tend to think that brilliant new inventions explode onto the scene and are immediately embraced by all (making fortunes in stock for the founders of companies that produce them). But that isnt usually the way it works. There is more typically a slow process of diffusion and adaptation, and this is certainly what happened with paper.

People have always made writing surfaces from the natural materials immediately around them. Some, like clay, require little preparation to be usable. Others, most notably papyrus and animal skins, need to be manufactured. Papyrus, from which the word paper is derived, is a rush or grasslike plant that grows in the Nile river delta. To make a writing surface, the plant is sliced lengthwise into long strips. These strips are laid in rows and allowed to dry in the sun, resulting in a highly durable surface that will accept marks on one side.

The process of turning animal skins into writing surfaces is more extensive: it involves raising the animals, skinning them and removing the hair, then stretching and sanding the skins. But the resulting product can be marked on both sides, and while papyrus can only be cultivated in limited regions of the world, livestock is raised in most climates as a source of food and clothing as well. The resulting surface can be remarkably thin, smooth, soft, and pliable. It is also extremely durable: pieces of vellum (from the same Latin root that gives us veal) have survived, with their marks intact, for a thousand years or more.

Medieval monasteries typically had to maintain extensive herds for food, of course, as well as books. The invention of paper provided a vegetarian alternative that could be made locally Instead of killing and skinning animals, plant fibers could be mashed into a pulp, spread out in thin layers, and dried. With proper treatment the resulting surfaces could accept forms written with a quill or brush.

The main advantage of medieval paper over animal skins was its lower price. Paper was actually more fragile and had a rougher surface than animal skins. It didnt accept inks and pigments nearly as well, and was harder to correct. It wasnt until the fourteen or fifteenth century, several hundred years after its introduction into Europe, that paper began to supplant animal skins. Initially this was due to its improved quality and availability. But with the invention of the printing press in the middle of the fifteenth century, which produced better results on paper than on most skins, the demand for paper increased dramatically.