Embattled

Saints

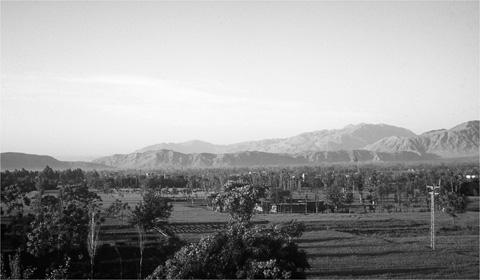

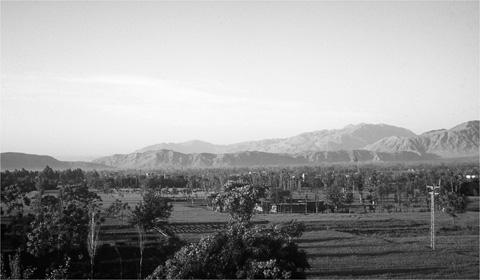

View of the Bara Valley looking southeast toward Pakistan.

Embattled

Saints

My Year with the Sufis of

Afghanistan

Kenneth P. Lizzio

Theosophical Publishing House

Wheaton, Illinois * Chennai, India

Learn more about Kenneth P. Lizzio and his work at www.questbooks.net

Find more books like this at www.questbooks.net

Copyright 2014 by Kenneth P. Lizzio

First Quest Edition 2014

Quest Books

Theosophical Publishing House

PO Box 270

Wheaton, IL 60187-0270

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Cover images:

Afghan village: karssar/iStock/Thinkstock.

Fresco: Edward Kim/Bigstock.com

Cover design by Kirsten Hansen Pott

Typesetting by Datapage, Inc.

appeared in different form in Central Asian Survey and the Muslim World, respectively.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lizzio, Kenneth P.

Embattled saints: my year with the Sufis of Afghanistan / Kenneth P. Lizzio.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-8356-0923-4

1. NaqshabandiyahAfghanistan. 2. Naqshabandiyah membersAfghanistan. 3. SufismAfghanistanHistory21st century. 4. SufisAfghanistanBiography. 5. Lizzio, Kenneth P. I. Title.

BP189.7.N35L59 2014

297.4'8dc23 2013040038

ISBN for electronic edition, e-pub format: 978-0-8356-2169-4

5 4 3 2 1 * 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

Contents

T ransliteration of words in Arabic, Persian, and Pashtu generally follows the conventions of the International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. Thus, I have omitted diacritical dots and long vowel markings. For the sake of simplicity I have shortened nisba endings so that, for example, the term Naqshbandiyyah is instead Naqshbandi. When quoting another writer, I have been obliged to use his or her system. I have tried to remain consistent in the spelling of personal names but did not feel justified in rewriting an authors name for that purpose. I have also made an exception in transliteration of personal names where it would have substantially altered the manner in which it is pronounced in the subcontinent. Generally, this applies to names in which the Arabic article al is elided; thus, while the name Saif ur-Rahman properly transliterated is Saif al-Rahman or ar-Rahman, I have retained the spoken form of the name.

Map of Afghanistan and Northwest Pakistan

I nterest in Islam has intensified in the West since the attacks of 9/11 and the uprisings of the Arab Spring. In the media, an array of think-tank specialists, academics, policy analysts, journalists, military strategists, and even Evangelical preachers have all expounded on the true nature of Islam. Books have proliferated on Islamic radicalism, Muslim terrorists, Middle East history and politics, tensions between Sunni and Shia, and dozens of related topics.

Behind this torrent of information are many competing agendas that are more likely to confuse than enlighten; some portrayals are informed and accurate while others amount to little more than partisan attacks. On balance, the image of Islamand of the complex civilization that it inspiredemerges as alien, exotic, conflicted, and prone to violence. Islam has replaced Communism as the new bugbear.

Other distortions are created less by what is said and written than by what is overlooked. In the public discourse on Islam, very little has been said about Sufism, the mystical dimension of Islam. Perhaps this omission is because Sufism, like all mysticisms, is perceived as ethereal and otherworldly. Or it may simply be dismissed out of hand as nonsense, the delusions of an irrational and backward people. Either way, it has little to do with real-world concerns of national security, access to oil, and political stability that any mention of Islam tends to evoke.

This book is an attempt to correct such misperceptions. It is an account of the history of a major branch of the Naqshbandi order of Sufism in South Asia, the Mujaddidi, and the year I spent living and studying with the then head of the order. At the time, these Sufis, primarily Afghans, were based in Pakistans unruly rural tribal region. As violence has increased there, they have been forced in recent years to relocate to the safety of the urban sprawl of the ancient city of Lahore.

The Naqshbandis, like other schools of Sufism, maintain that in addition to sensory and intellectual modes of cognition, a third mode exists: gnosis. Based on the principle that modes of knowing and being are linked, gnosis is attained when the disciple follows a path (tariqa) of moral purification and mental contemplation under the initiation and guidance of a spiritual master. The process is intended to undermine narcissistic and exclusive identification of consciousness with self. With the aid of the shaikh, the disciple progresses through more advanced stages and states of consciousness, culminating in realization of the disciples conscious identity with spirit as the fundamental ground of existence.

Though I did not fully appreciate it at the time, the Naqshbandi way of life I observed is facing threats to its very existence. Such threats are nothing new. The British and Russian empires, for instance, in their Great Game of colonial rivalry that once included central Asia, each tried to subdue them but failed in the end. Today, the Naqshbandis face new perils that are less overt but just as lethal.

One peril lies in the creeping secularization of Islamic society, a process set in motion more than a century ago by colonization and industrialization. Another is emerging from within Islam itself as one radical fundamentalist sect after another morphs into existence to assert, often forcibly, its own exclusive and narrow interpretation of Islam in which there is no place for Sufis.

Amid the welter of competing claims for Islamic truth, Sufis may provide the key to resolving the differences. Historically, Sufism has been the well from which Islam has drawn for spiritual revival during troubled or irreligious times. Whatever other roles they choose to playand they are diversemystics are essentially technicians of the transcendent. And because Sufis traffic in matters that are timeless and cross-cultural, they help outsiders understand not only the true nature of Islam but the deeper meaning of all religions.