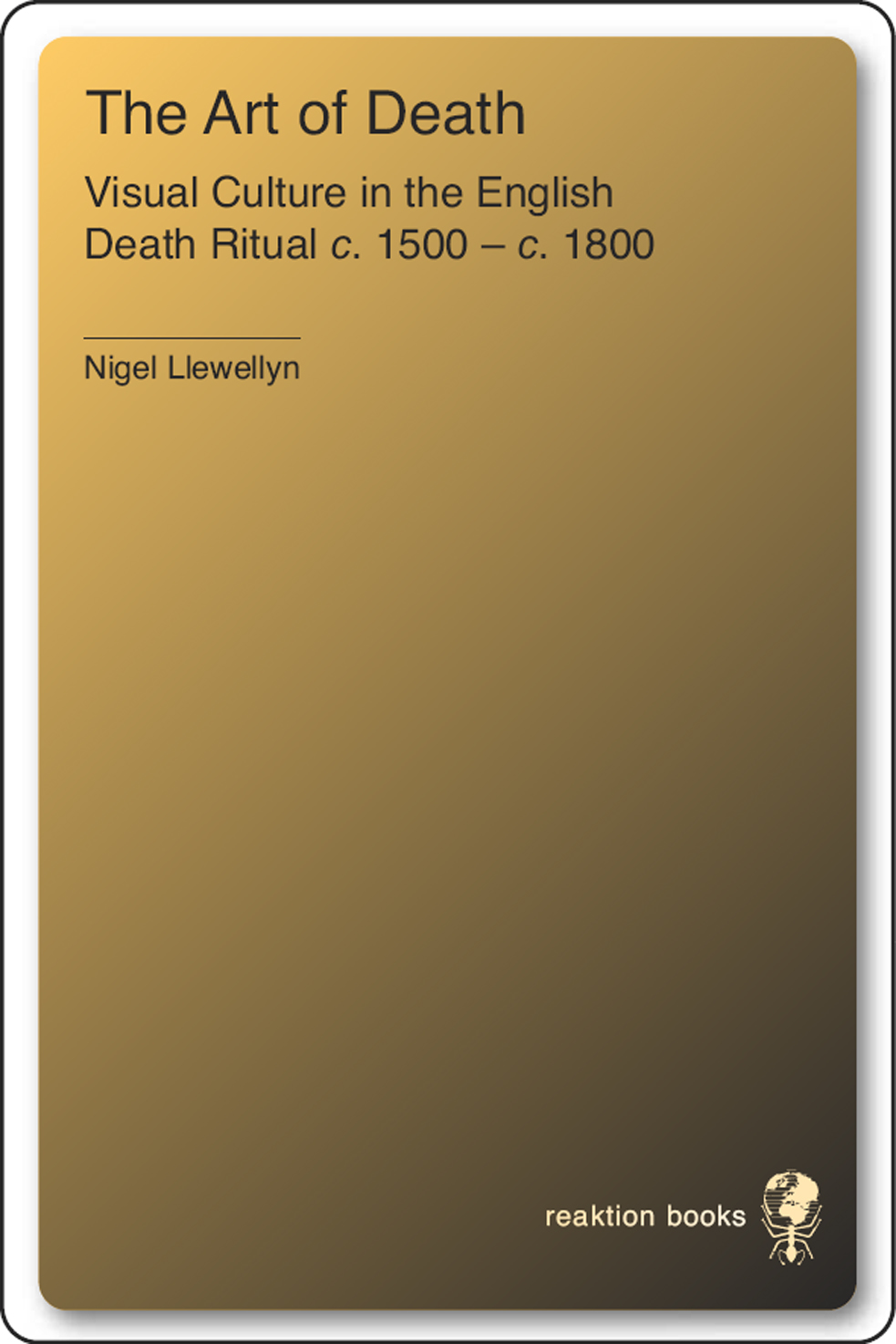

THE ART OF

DEATH

VISUAL CULTURE IN

THE ENGLISH DEATH RITUAL

c. 1500 c. 1800

NIGEL LLEWELLYN

PUBLISHED IN ASSOCIATION WITH

THE VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM

BY REAKTION BOOKS LONDON

For Clare

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum

Distributed throughout the world to the booktrade

by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

First published 1991, reprinted 1992, 1997

Copyright 1991 the Board of the Trustees of the

Victoria and Albert Museum and Nigel Llewellyn

All rights reserved

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Designed by Humphrey Stone

Jacket design by Ron Costley

Photoset by Rowland Phototypesetting Ltd,

Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by BAS Printers Ltd,

Over Wallop, Stockbridge, Hampshire

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Llewellyn, Nigel

The art of death: visual culture in the English death

ritual c. 1500 c. 1800

1. Visual arts. Special subjects. Death

I. Title

704.9493069

eISBN: 9781780231518

CONTENTS

1. Robert Walker, John Evelyn, oil on canvas, 1648.

INTRODUCTION

H ow did our ancestors die? Biographers, demographers and historians of medicine can provide some answers to this question, but the full cultural complexity of death eludes conventional historical methods. Death is both a moment in time and a ritualized process; it also refers to a physical transformation and a social phenomenon. Such a complex picture demands flexibility in historical discourse; for example, all of what was meant by dying cannot be disclosed by data on death rates plotted on a graph.

For one reason or another, everyone finds death difficult; as the seventeenth-century poet Henry Vaughan wrote: Yet by none art thou understood. Society expects historians, like scientists, to reveal the truth about contradictory phenomena; but death resists such an interpretation. The whole subject is simply too complex to be treated in one single history. Rather, there are many histories of death, of which this an essay on the visual culture of the post-Reformation ritual is but one.

In later sixteenth-century England, and beyond into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a sophisticated ritual was developed in response to death, accompanied by a rich culture of visual artefacts. The role that such images and objects played has never been investigated; but their part, I would suggest, was central in establishing and sustaining all the processes of the English death ritual over this post-Reformation period. I hope that the complexities of this ritual do not make my arguments impossible to follow. The structure or narrative I have adopted does, however, need a few words of explanation.

The objects will be discussed in a sequence which will be unfamiliar to readers used to the traditional pattern of art-historical literature. The chapters are neither on chronological themes nor are they studies of topics such as medium, artist and patron, subject-matter or genre. What has determined the structure of the book is the course that was taken by the death ritual, which, I argue, was directly responsible for producing this particular set of cultural artefacts. The story commences with the role of prints and pictures in preparing the spirit prior to the moment of physical death; another topic taken in the opening section describes how representations of the moment of death were expected to teach the living how to die. This is followed by a discussion of the visual culture associated with the decaying natural body and further sections on the funeral rites, mourning, commemorative art and, finally, illustrations of the poetic and historical topoi of the contemplation of the ancient tomb. Despite the span of time suggested by the subtitle, I have not set out to survey the whole period with equal attention. The Reformation had some immediate effects on the visual culture of the English death ritual; other aspects of the problem took many generations to resolve. This inconsistency is reflected in the examples given and the objects discussed and illustrated, which tend to favour the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. However, I would not want to suggest that many of the most important themes in the book could not have been illustrated by eighteenth-century objects and, as is well known, there was a spectacular visual culture of death in the nineteenth century.

In planning this book I have had to decide how to juxtapose the theories about death held by anthropologists, sociologists, psychologists and others with discussions about objects. This is a standard dilemma for the art historian and I have decided not to section off theory in an opening apologia but rather to feed regularly into the text questions such as how visual artefacts emphasised continuity; what kind of visual representations were suddenly required in the face of death; why was the human person conceived both as a body and a personality not homogeneous but imagined in diverse ways; and why were there tensions and conflicts between the private and public aspects of death, grief and mourning.

Throughout, I have juxtaposed discussions of this kind with the objects to which they relate. It is, of course, not a perfect solution. Some might argue that it is important to know about the theory of the Two Bodies before considering a single picture or image. Such a strategy would, however, have set up the kind of theoretical ghetto which might all too easily be isolated from the artefacts themselves. So, I have decided to follow the overall narrative shape of the exhibition itself and introduce theoretical material rather more organically. Should the reader reach the final page, all the main themes will have been made available.

Some of the sub-headings refer to groups of objects and are self-explanatory; others introduce sections which treat more abstract ideas and may appear obscure and even irrelevant. In the process of labelling, years of study of epitaphs and printed ephemera associated with death have left their mark: I seem quite unable to resist terrible puns.

I THE OBJECT OF COMMEMORATION

A few embroidered words worked on a sampler dated 1736 illustrate the cultural complexity of the ritual that followed a death in post-Reformation England:

When I am dead, and laid in grave,

And all my bones are rotten,

By this may I remembered be

When I should be forgotten.

In one sense this simple artefact is clearly intended to be commemorative. The author is imagining the world after her death. Yet the consistent use of the first person and the confused array of tenses reveals a more complex sense of time and purpose in these verses. The I suggests that the embroiderer was party to the writing of the text and, we assume, to the making of the sampler itself. Today, commemorative art is made for other people; it is rarely by artists about themselves. So what precisely is it that the sampler will commemorate? We might imagine the person in a gruesome future state, as a physical body in a state of transition the rotten bones referred to by the author. But there are other aspects of the person besides. Though their author exists in the present and has a living, functioning body, the words address a future reader who, in that time to come, will be contemplating the past. Several bodies can be inferred in this short rhyme. Nearest to us is the living body holding the needle and responsible for the embroidery. Further away, in the future, there is the dead body, divided in turn into two aspects. The first, the social body after death, is sustained in our memories by artefacts such as this very sampler; the second, the natural body after death, is lifeless, alien and used up. One of the most problematic aspects of the visual culture made to accompany the English death ritual is its habit of obscuring precisely which of these several bodies is its concern.