Marshall - The Reformation: a very short introduction

Here you can read online Marshall - The Reformation: a very short introduction full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Europa;Oxford etc, year: 2009, publisher: Oxford University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Reformation: a very short introduction: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Reformation: a very short introduction" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Marshall: author's other books

Who wrote The Reformation: a very short introduction? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Reformation: a very short introduction — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Reformation: a very short introduction" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Reformations

It starts in a thunderstorm in the summer of 1505. On the road near Erfurt, in the Germany principality of Saxony, a young law student is caught in the downpour, and fears for his life amidst the ferocious strikes of lightning. He prays to St Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary, offering a bargain: if she will spare his life, he will become a monk. A fortnight later, he bangs on the door of the Erfurt house of the reformed Augustinian friars, one of the strictest of all the religious orders.

Martin Luther told the story about himself, decades later, and it may not have happened that way. But everything about the tale is significant: the intensity of the medieval cult of the saints, the combined quest for material and spiritual salvation, the setting in Germany. Asking why the Reformation started in Germany is a bit like asking why the Communist Revolution started in Russia, or the telephone was invented in America it happened there because it happened there. Some important preconditions seem absent. In contrast to Hussite Bohemia, or Lollard-flecked England, Germany was pretty much a heresy-free zone in the decades around 1500, with little formal challenge to the authority of the Church. What was distinctive was its political structure. Unlike the emergent national monarchies of France, England, and Spain, Germany was politically fragmented a patchwork of petty princedoms, ecclesiastical territories, and self-governing cities, under the nominal suzerainty of the grandly named Holy Roman Emperor. The office was elective, the emperor chosen by seven territorial Electors (including three archbishops). At the time of Luthers entry into the monastery the throne was occupied by the Habsburg dynasty, in the person of Maximilian I. Imperial business was conducted at meetings of the Reichstag, or diets of the imperial estates, at which electors, princes, and towns were all represented, and took the opportunity to formulate their grievances, often about the need for reform in the Church.

Germans compensated for political weakness with a passionate cultural and linguistic nationalism. The international scholarly movement for the revival of ancient learning known as humanism (not to be confused with modern secular humanism) had a German limb, which found in the writings of the Roman historian Tacitus descriptions of a free and vigorous Germanic people, underlining a contemporary sense of subjugation. The nasty side of German nationalism was an intense Italo-phobia. The far side of the Alps was a source of moral and cultural corruption and, with one brief exception, all 15th- and 16th-century popes were Italians. There was a political context for this prejudice; Germany was the one important part of Western Europe outside Italy itself where the papal aspiration to direct monarchical government of the Church still had some real purchase. The kings of France, Spain, and England were dutiful sons of Rome. But in a quiet way they had been nationalizing the Church in their territories, securing the right to nominate bishops, for example, and using that power to reward loyal servants. The vacuum of centralized control in Germany meant that popes retained greater power to appoint to ecclesiastical offices, and, via the prince-bishops, to extract taxation from the populace always a fertile source of bitterness. Anticlericalism an antipathy to the political power of the clergy does not equate to rejection of Church teachings. All the evidence suggests that early 16th-century Germany was a pious and orthodox Catholic society. But national and anticlerical resentments abounded, and they found their voice in Luther.

On 31 October 1517, Luther nailed a long list of points for disputation Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the church near the castle in the Saxon capital of Wittenberg. It is a moment that has reverberated in history, the day on which the Protestant Reformation was born and the Middle Ages suddenly dropped dead. The reality is more prosaic. Some scholars have denied that the Theses were ever posted at all. It seems likely that they were, but this was hardly a world-shattering act. Luther was now a professor at the recently founded University of Wittenberg, and the conventional method of initiating academic debate within the theology faculty was to post theses in advance. Because of its handy location, the door of the Castle Church served as the universitys bulletin board, and Luthers gesture has been seen as no more dramatic than pinning up a lecture list in a modern college. The Theses themselves were not particularly revolutionary: they did not reject the authority of the pope, or call for the founding of a new church, and they addressed a fairly minor and obscure point of theology. There was in 1517 no blueprint to reform the Church, no foreseeable outcome. Political circumstances, combined with Luthers stubbornness and eventual willingness to think the unthinkable, allowed it all to get out of hand.

The original issue was indulgences. These were an outgrowth of the Churchs teaching on sin and penance. Confession to a priest guaranteed forgiveness from God, but the legal-minded thinking of the Middle Ages maintained this still left a debt to be paid for sin. Some of this could be worked off in this life through performance of penances. The rest would be extracted in purgatory a place in the afterlife where the souls of all but the truly wicked and the excessively saintly would suffer for a while before being admitted, debt-free and purified, into heaven. Indulgences were a certificate remitting some of the punishment due in purgatory in exchange for performance of a good work (they were originally developed as an inducement for people to go on crusade) or giving money to a good cause. Popes argued that, as heads of the Church on earth, they could draw on the surplus good deeds of the saints to underwrite indulgences. The system had a coherent underlying logic, but it was open to abuse, and had been criticized by some thinkers, especially humanists, long before Luther. The papal indulgence issued in 1515 looked particularly dodgy from the viewpoint of moralists and reformers. It was designed to raise money for a prestige project, the building of the new Renaissance Basilica of St Peter in Rome. Its sale in Germany was arranged by one of the worst of the worldly prince-bishops, Albrecht of Brandenburg, who was to keep a share of the proceeds to pay back the bankers who had financed his purchase of the archbishopric of Mainz. Fronting the campaign was a Dominican friar, Johan Tetzel, who went about his business in an effective but crude and materialistic way, employing the advertising jingle, as soon as the coin in the coffer rings, a soul from purgatory to heaven springs. Luther was appalled by Tetzels methods, and by a popular response which seemed to show no understanding of the need for true repentance. There was also no love lost between the Dominicans and the Augustinians. When Pope Leo X first heard of the controversy, he dismissed it lightly as a quarrel among friars.

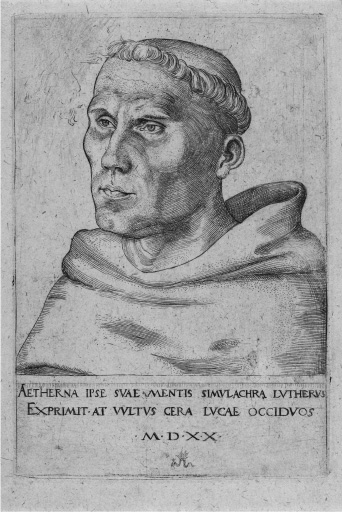

1. Lucas Cranachs 1520 portrait of Martin Luther depicts him as still very much the Catholic friar

Luther meanwhile was edging towards a momentous conclusion if the Church and pope could or would not reform an evident abuse like indulgences, then something must be wrong with the entire structure of authority and theology. For some years Luther had been nurturing doubts about the elaborate ritual mechanisms for acquiring merit in the eyes of God, and coming to the view that faith alone was sufficient for salvation. Luthers radicalization came into full view in the course of a 1519 debate staged in Leipzig, against a clever orthodox opponent, Johan Eck. Earlier, Luther had conventionally appealed against the pope to the authority of a general council. But by comparing Luther to Jan Hus, Eck manoeuvred him into declaring that the Czech heretic had been unjustly condemned by the Council of Constance, and that councils, like popes, could err in matters of faith. This left only the scripture as an infallible source of religious authority. After Leipzig, there was no going back. Luther was excommunicated by Leo X in 1520, and responded, characteristically, by publicly burning the papal bull of excommunication in Wittenberg. He also published a series of pamphlets castigating the Babylonian captivity of the Church, rejecting the necessity of obedience to the Churchs canon law, reducing the number of sacraments from seven to three, and calling on the emperor and German nobility to step in and reform the Church.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Reformation: a very short introduction»

Look at similar books to The Reformation: a very short introduction. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Reformation: a very short introduction and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.