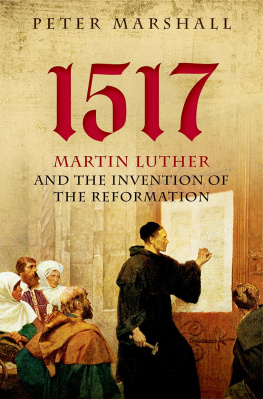

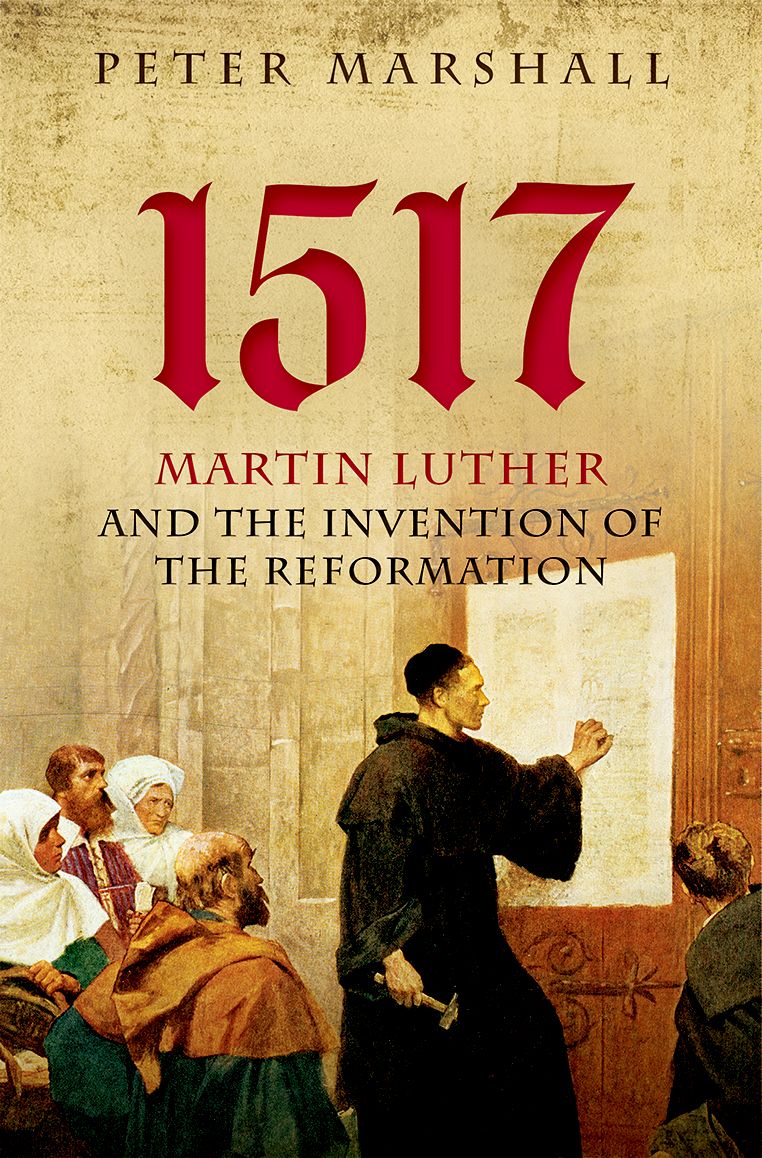

1517

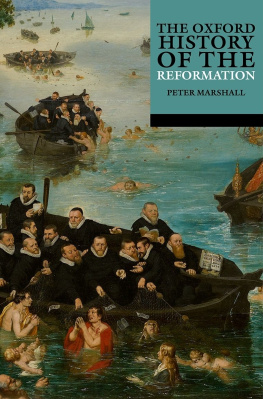

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Peter Marshall 2017

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2017

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016963351

ISBN 9780199682010

ebook ISBN 9780191504617

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For Bernard Capp

Acknowledgements

A number of institutions and individuals have helped in the writing of this book, which was made possible by a timely grant of research leave from the University of Warwick and some welcome financial assistance from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Among various scholarly supporters, I am particularly indebted to Scott Dixon, who not only offered me an advance viewing of his seminal forthcoming article on the Ninety-five Theses, but read my entire manuscript with great care and kindness, and saved me from several blunders. David Whitford similarly brought the skills and sensibilities of a seasoned Luther expert to drafts of the early chapters, and reassured me I was not chasing my own tail. I am also grateful to Tal Howard, for allowing me access before publication to his important book on Remembering the Reformation, and to Barry Stephenson for answering my queries about Wittenberg and directing me to some rich visual sources. Some of the material in this book was first aired at a conference at St Patricks College, Maynooth, in the spring of 2015: I am indebted to Declan Marmion and Salvador Ryan for the invitation to that event, and to other participants, particularly David Bagchi, for lively and encouraging discussion. I must also thank Angela McShane for alerting me to the existence of the splendid Luther beaker in the Victoria and Albert Museum, and Charlotte Methuen and Christoph Mick for assistance with the translation of some tricky German passages. At OUP, Matthew Cotton has been an outstanding editor, ever cheerful, patient, and supportive, and I am equally grateful to Luciana OFlaherty and Kizzy Taylor-Richelieu for steering me smoothly through the final stages of the manuscripts preparation and submission. My loved onesAli, Bella, Maria, and Kithave, as always, helped me in innumerable ways, not least by providing much-needed IT support. The dedication, to a Warwick colleague, represents an inadequate recompense for many years of warm friendship and wise counsel.

Peter Marshall

Leamington Spa

October 2016

Contents

Document

It is one of the greatest remembered moments in western history. With one action, lasting no more than a few minutes, a solitary monk sets in motion a chain of events which will change forever the religious, political, and cultural development of Europe, and of the wider world beyond. It is the moment, many people have thought, when the middle ages come suddenly to an end, and modernity commences. A moment which asserts the rights of individual conscience against unquestioned ancient authority; of public probity against corruption and venality; of reasoned faith against superstition and fear. The date is 31 October 1517. The place is Wittenberg, an unprepossessing town on the River Elbe in north-eastern Germany. The monk is Martin Luther, a thirty-three-year-old member of the Eremitical Order of Augustinian friars. The action is the nailing to the doors of the Schlosskirche, the church attached to Wittenberg Castle, of a single-sheet document. The document is a list of ninety-five thesesassertions or propositionsagainst papal teaching on indulgences. The result is a revolution.

Everyone, more or less, has heard of the Ninety-five Theses. They constitute one of the most famous written works of the last millennium. If a text can be iconic, then the Ninety-five Theses surely meets the criteria. Anthologies of Great Documents of Western Civilization, Milestone Documents in World History or 100 Documents That Changed the World regularly reprint them, alongside such works as Magna Carta, the American Declaration of Independence, The Communist Manifesto, and the Charter of the United Nations. A British daily newspaper recently ranked them, together with the 1833 Act abolishing slavery in the British Empire, the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, Maos Little Red Book of 1964, and Watson and Cricks 1953 detailing of the molecular structure of DNA, as one of 10 Documents that Changed the World.

The allegedly world-changing character of the Ninety-five Theses has ensured a place of honour in the mental library of European culture. Martin Luther wrote and published a great deal between 1517 and his death in 1546, but only those who have made some specialist study of his life and career can without difficulty recall the titles of any other of his works. For many people, the Ninety-five Theses are synonymous with Martin Luther, and Luther is synonymous with the Reformation, and everything which that word has come to represent in our understanding of the past. Admittedly, detailed knowledge of what the Ninety-five Theses actually say may be at something of a premium. Their numerical quantity certainly militates against easy rote learning of their contents. The compilers of a book of 101 Great Cultural Lists, beginning with the Seven Wonders of the World, have admitted that because we wanted to include only lists that could plausibly be memorized, we reluctantly excluded Luthers ninety-five theses.

But, in other ways, the sheer number of the Theses serves to reinforce their potency as a cultural point of reference. How could indulgences have been reputable or defensible when it was possible to think of so manyninety-five!good arguments against them? Ninety-five was in 1517 an entirely arbitrary number, without any previous mathematical or symbolic associations (and, as we shall see, it was not entirely clear to everyone in 1517 that the assorted Theses did add up to ninety-five). Yet, in modern times, the number has assumed a totemic significance for the definitive articulation of a compelling case. If Ten Commandments still represents the ultimate framing mechanism for any programme or manifesto, Ninety-five Theses arguably runs a close second.