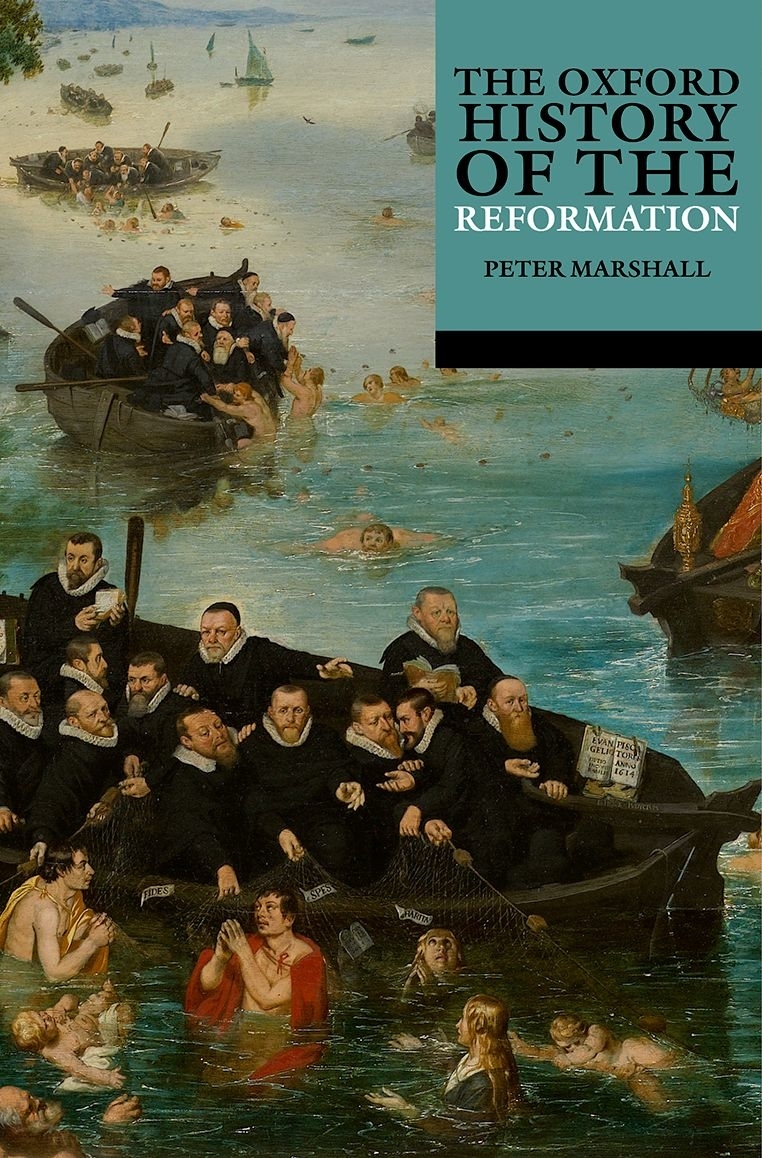

The Oxford History of the Reformation

PETER MARSHALL FBA was born and raised in the Orkney Islands, and educated at the University of Oxford. Since 1994, he has taught at the University of Warwick, where he has been Professor of History since 2006. A leading specialist in the history of the Reformation, particularly its impact in the British Isles, he has written nine books and over sixty articles on these themes. He is a two-time winner of the Harold Grimm Prize (for best article in Reformation Studies), and his account of the English Reformation, Heretics and Believers, won the Wolfson History Prize in 2018. Peter is married with three daughters, and lives in Leamington Spa.

The seven historians who contributed to the Oxford History of the Reformation are all distinguished authorities in their field.

simon ditchfield , University of York

carlos eire , Yale University

brad s. gregory , University of Notre Dame

bruce gordon , Yale University

peter marshall , University of Warwick

lyndal roper , University of Oxford

alexandra walsham , University of Cambridge

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Oxford University Press 2022. The text of this edition was first published in The Oxford IllustratedHistory of the Reformation in 2015.

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2015

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014941339

ISBN 9780192895264

ebook ISBN 9780192648389

Printed and bound in the UK by

Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Editors Foreword

Half a millennium has now passed since the Augustinian friar Martin Luther drew up a provocative set of questions for discussionhis Ninety-Five Theses against Indulgencesand may have nailed them to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. He did not intend it, and no one at the time foresaw it, but his action set in motion the momentous process of religious change which came to be called the Reformation, which gave birth to a new form of Christianity soon to be known as Protestantism, and which created bitter and lasting disharmonies in European (and later, global) social, cultural, and political lifedissonances whose echoes are still clearly audible today. Whether we like it or not, we are all children of the Reformation. But the nature of our collective inheritance has always been a contentious and disputed one.

As an object of historical study, the Reformation is an old topic with a new face. Recent scholarship has not sought to deny or refute some long-held assumptions: that the changes following from Martin Luthers protest in Germany were extremely important ones; that they ended up transforming numerous aspects of European culture and society; and that they mark a kind of boundary between the medieval and modern worlds. But the manner in which these changes were brought about, the roles assigned to particular individuals and groups, the length of time they took, and the question of whether they self-evidently represented progress or improvementthese have all been discussed and debated over the course of the last few decades in ways which would undoubtedly have puzzled or perplexed earlier generations of historians. The aim of the current volumewhich brings together a team of scholars at the very forefront of current Reformation researchis to bring out some of the ways in which over recent years our understanding of the Reformation has become more complicated (and therefore more interesting), while retaining a clear and coherent perspective on the balance between continuity and change. The chapters focus on particular themes, with individual stories to tell, and particular interpretative problems to discuss, but collectively they supply both a broad narrative of the key developments, and a cohesive overall assessment of how the Reformation looks from the vantage point of the third decade of the twenty-first century.

What readers will not find in these pages is much suggestion that the religious debates and conflicts of the Reformation era were merely a kind of codea necessary language (since that was all that was available to contemporaries) for conducting and resolving deeper clashes over political power and economic resources. Our approach is traditional to the extent that we believe that the actual content of ideas mattered, and had the power to motivate individuals to act in ways that were not always in their own material best interests. But, equally, each of the contributors here is fully aware that, in the period we are studying, religion was not what it has since become in much of the modern West: a narrowly defined, discrete realm of action and experiencethe occasional reflective column in the opinion pages of a newspaper, the declining habit of church on Sunday. Our subjects inhabited societies where it was (almost) universally believed that God had not only created the world, but continued to take a close, direct, and controlling interest in every aspect of its governance and workings. To study the impact of the Reformation, therefore, is necessarily to pursue the political, the social, the culturalquestions of relations between rulers and subjects, masters and servants, and between women and men, parents and children. Over the longer term, the emergence of something like the modern Western concept of religionan essentially private matter, the sincere adherence to which was compatible with other loyalties and obligations, and which might take acceptably plural formsmay have been one of the key outcomes of the Reformation. If so, it was a result few at the time foresaw and fewer still would have welcomed. That the Reformation represents a case study in the law of unintended consequences is one of the recurrent themes of this book.

Alongside a Reformation more unpredictable in its course and consequences than earlier generations supposed, we now also have one which was wider (theologically), bigger (geographically), and longer (chronologically) than in the days, not so very long ago, when textbooks on the Reformation largely confined themselves without embarrassment to developments in (western) Europe, to the followers of Luther and Calvin, and to the short period between 1517 and 1559. Luther and Calvin still matter, of course. Without them, and without the challenging and compelling religious ideas they formulatedjustification by faith alone, the doctrine of double-predestinationthe religious changes of the sixteenth century would have looked very different, and might well bear another name. The chapters by Lyndal Roper and Carlos Eire demonstrate how the spiritual, and physical, journeys of these key individuals, though they began in very traditional places, led and pointed to some truly new destinations. But Luther and Calvin, and the -isms to which they unwillingly lent their names, should certainly no longer define the character of the Reformation for us, as if in some pure and perfected essence. Brad Gregorys chapter highlights the importance of that loose network of reforming individuals and ideasknown variously as radicals or Anabaptistswho have nearly always been seen as marginal or exceptional, and as lying firmly outside a Reformation mainstream. But he warns that this perception owes much to uncritical hindsight, and he argues that those anti-Roman groups and individuals who rejected the interpretations of scripture supplied by Luther and the other magisterial reformers have as much right as anyone to be considered both founders and heirs of a quintessentially Reformation tradition.