This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1963 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

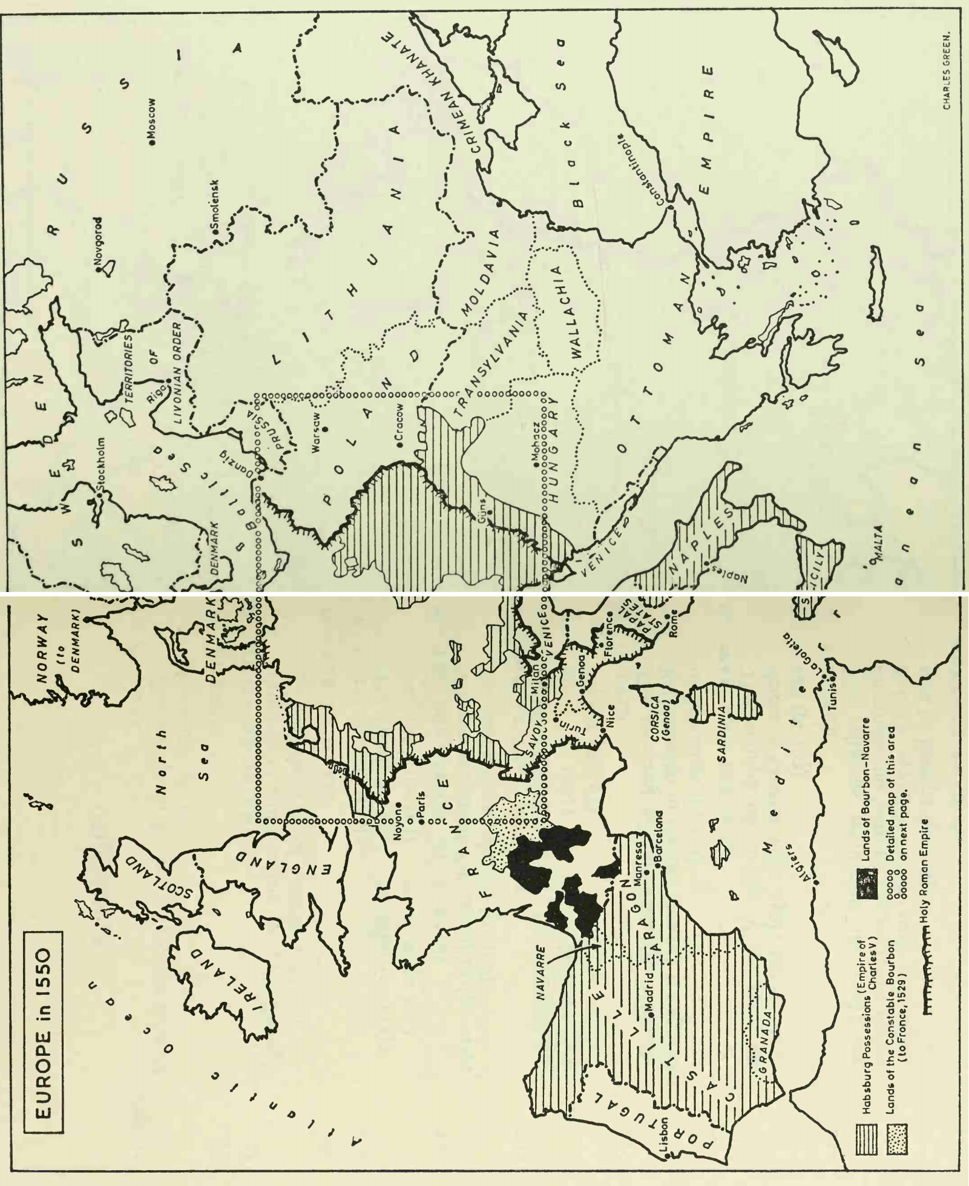

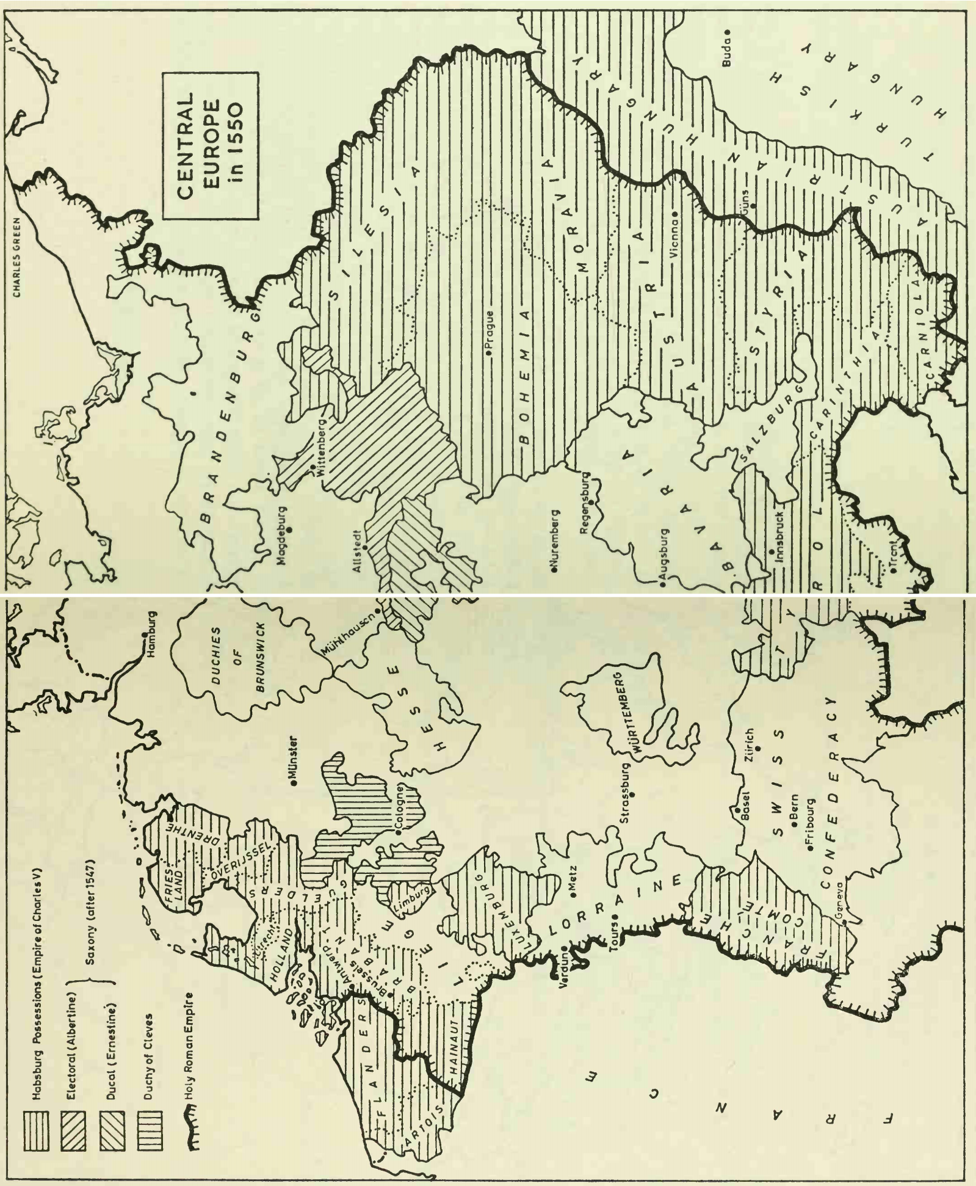

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

HISTORY OF EUROPE:

REFORMATION EUROPE, 1517-1559

BY

G. R. ELTON

Edited by J. H. Plumb

PREFACE

Europe in the early sixteenth century remains a magnet to student and reader alike. The continued flood of studies is one justification for this attempt to tell the story once more; the continued and lively interest in it of so many people is another. However, it is idle to hope that in a relatively short compass one could adequately deal with all aspects of the age, and I have thought best to centre the narrative on the religious upheaval. The Reformation as a movement in religion and theology, placed within its setting of politics, economics and society, is the theme of this book. This has involved me in passing judgement on some very controversial people and issues, and I must fear that I shall not always seem to have observed the impartiality which it has been my ambition to attain. However, if I cannot hope to have pleased all sides, I can at least suppose that I have in different places displeased them all equally.

My sincere thanks go to those whose counsel and encouragement have helped in the writing of this book: a pleasure in itself, rendered more pleasing by the interest of others. In particular, Dr. J. H. Elliott has generously saved me from error, and Professor G. R. Potter, in addition to performing the same service in other parts of the book, has added enormously to the pleasant burden of obligation by reading the proofs. My overriding debt is recorded in the dedication.

G. R. ELTON

Cambridge

December 1962

CHAPTER ILUTHER

I

On 31 October 1517, Dr. Martin Luther, professor of theology in the recently founded Saxon University of Wittenberg, nailed a paper of Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the Castle Church in that town. There was nothing unusual about this. Any scholar who wished to defend any propositions of law or doctrine could invite learned debate by putting forth such theses, and church doors were the customary place for medieval publicity. Luthers Ninety-Five attacked the practice of selling indulgencesdocuments offering commutation of penance for money payments. Certainly Luther had no thought of starting a schism in the Church. These were not the first theses he had offered for public disputation, nor did they embody necessarily revolutionary doctrines. Nevertheless, the day continues to be celebrated in Lutheran countries as the anniversary of the Reformation, and justly so. The controversy over indulgences brought together the man and the occasion: it signalled the end of the medieval Church.

Martin Luther (1483-1546) was the son of a miner of Eisleben in Saxony. Since he early showed intellectual promise, his father intended him for the canon law, a profession of honour and profit; he was extremely angry when the boy instead found that his studies at the University of Erfurt inclined him to theology and contemplation. In 1505, Luther entered the order of the Austin Friars at Erfurt; in 1508, he was appointed a professor at Wittenberg. For nearly ten years he read and thought, wrestling with his humanity in his desperate search for salvation. This young friar and academic, obscure enough in all conscience, hid behind the heavy peasants face a mind exceptional in its passion, intensity, stubbornness and subtlety, a mind which could not rest at ease with the prospect of pastoral and professional success for which in other ways he seemed so well fitted. He was a solid scholar, trained and for a time sunk in the late-medieval scholasticism of Occamist nominalism, as transmitted by the pietist Gabriel Biel who taught that despite the Fall man had power to seek salvation of his own free will. These teachings soon ceased to satisfy Luther who was to revolutionise theology because in fact he found himself in a state of despair before God. He wanted the assurance of being acceptable to God, but could discover in himself only the certainty of sin and in God only an inexorable justice which condemned to futility all his efforts at repentance and his search for the divine mercy. In vain he tried to solve his difficulties by all the mortifications and other means advised by his Church and Order. When he found the answer, it grew directly out of his total sense of helplessness in the face of God ( coram Deo ), and out of his reading of St. Paul with the assistance of St. Augustine. He went back to the Fathers and finally to the Gospel, till he understood that the righteousness of God ( iustitia Dei ) meant not Gods anger at sin but His willingness to make the sinner just (free of sin) by the power of His love bestowed freely on the true believer. Luther held that man was justified (saved) by faith alone: the words sola fide came to be the watchword and touchstone of the Reformation. Man could do nothing by his own workswhether works of edification like prayer, fasting, mortification, or works of charityto compel justification. But if he believed, God of His grace would give him the gifts of the Holy Spiritsalvation and eternal life. The means of grace were in Jesus Christ; faith was created by abandoning oneself to the message of the gospel, to what Luther called the Word.

Of course, this doctrine was not new; it hardly could be in a religion which for 1500 years had explored every possibility within itself. Luther did not think it new: to him it was the truth of the gospel. The study of his lectures in the years before he became a public figure has shown the development of his theology and illuminated its close links with late-medieval teaching and mysticism, with views, that is, on the relationship of God and man which laid the stress not on institutional and sacramental expedients but on the search of the individual soul. Nevertheless, Luthers views proved revolutionary because they concentrated with such incisive singlemindedness on the total inability of man to help himself to his own salvation. He took seriously the accepted doctrine of Gods omnipotence and therefore (as it were) sole monopoly of free will. In consequence, as the event was to show, Luther had rendered superfluous the whole apparatus of the Church, designed to mediate between man and God. If mans justification depended solely on Gods infusion of grace into the believing soul, there was no need for a priesthood alone capable of performing the sacramental acts through which (as the Church taught) the way was opened for grace to enter man. Beside the doctrine of justification by faith alone there soon stood its companion, that of the priesthood of all believers. At first, Luther had no quarrel with the pope, the hierarchy or the Church, and he never lost his conservative sense of an order embodied in institutions. He proved in many ways a most reluctant revolutionary who never wished to abandon tradition, unless his reading of scripture compelled him to it. Thus, when a more radical disciple protested against the elevation of the host in the mass, asking, Where does Christ command it, Luther replied: Where does He forbid it? But he shared the widespread dissatisfaction with the standards of the clergy and in particular had been shocked by what he saw of the papal Curia when he visited Rome in 1510. He had his share of German nationalism and bigotry, with their violent dislike of all those subtle Italian devices which, prejudice alleged, were milking honest Germans and sending them to perdition. His own experiences had turned him against the futility of monkish asceticism as well as the indecency of its hypocrisy. Thus he was ready enough to give voice to the prevalent anticlericalism of the day.