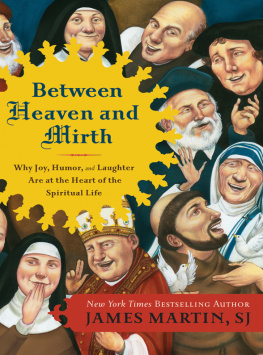

B ETWEEN H EAVEN AND M IRTH

Why Joy, Humor, and Laughter Are

at the Heart of the Spiritual Life

J AMES M ARTIN , S.J.

For my mother and father,

who taught me how to laugh;

for my sister and brother-in-law,

who laugh with me;

for my nephews,

who make me laugh;

and for my brother Jesuits and friends,

who remind me to laugh at myself.

Contents

Introduction

Excessive Levity

M IKE IS ONE OF the funniest people I know. A Catholic priest in his mid-sixties, he regales his friends with clever stories, boasts superb comic timing, and has perfected an inimitable deadpan look. Today Mike is a popular professor at Fordham, a Catholic university in New York City, where his lighthearted sermons attract crowds of students to Sunday Masses. Its nearly impossible to be downhearted or discouraged in his presence.

But Mikes contagious humor wasnt always valued. And forty years ago the Jesuitsthe Catholic religious order to which Mike and I belonghad an odd custom that made this clear. At the time, the young Jesuits in training were required to publicly confess their faults to the men in their community as a way of fostering their humility. This had been a long-standing practice in many religious orders, especially in monastic orders. (It sounds strange but, as the saying goes, the past is a different country. And the past in religious orders is a different world.)

So, for example, at a weekly gathering of the priests and brothers, a young Jesuit might confess that he hadnt said his evening prayers. Or that he had nodded off during a particularly dull homily. Or that he had said uncharitable things about another person in the community. This was supposed to help the young Jesuit become more humble, more attentive to his shortcomings, and more eager to correct them. On top of that, each young Jesuit was supposed to confess things privately, to the head of the community.

One day Mike, who was known for his high spirits, felt guilty. Earlier in the day, during Mass, he couldnt stop laughing about something that struck him as hilarious. He felt he had been acting silly and undignified. So Mike walked into the office of the head of the Jesuit community, an elderly priest with a well-earned reputation for seriousness.

Mike took his seat and prepared for his admission of guilt.

Father, he said, I confess excessive levity.

The priest glowered at Mike, paused, and said, All levity is excessive!

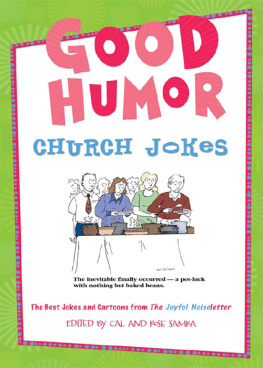

I N SOME RELIGIOUS CIRCLES joy, humor, and laughter are viewed the same way the crabby priest saw levity: as excessive. Excessive, irrelevant, ridiculous, inappropriate, and even scandalous. But a lighthearted spirit is none of those things. Rather, it is an essential element of a healthy spiritual life and a healthy life in general. When we lose sight of this serious truth, we cease to live life fully, truly, and wholly. Indeed, we fail to be holy. And thats what this book is about: the value of joy, humor, and laughter in the spiritual life.

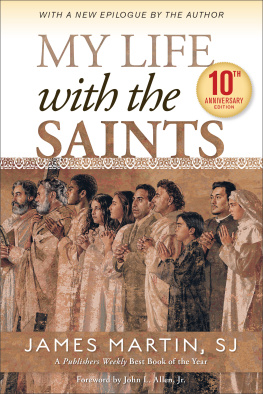

This book had its genesis a few years ago when I began to give talks based on a book called My Life with the Saints, a memoir telling the story of twenty saints who had been influential in my spiritual life. In a short while I noticed something surprising. Wherever I spokewhether in parishes, colleges, conferences, or retreat centerswhat people wanted to hear about most was the way the saints were joyful people, enjoyed lives full of laughter, and how their holiness led inevitably to joy. To a degree that astonished me, people seemed fascinated by joy. It was almost as if theyd been waiting to be told that its okay to be religious and enjoy themselves, to be joyful believers.

Still, many professional religious people (priests, ministers, rabbis, and the like) as well as some devout believers in general give the impression that being religious means being dour, serious, or even grumpylike Mikes superior. (Um, uptight, Mike said recently, when I asked what the guy was like.) But the lives of the saints, as well as those of great spiritual masters from almost every other religious tradition, show the opposite. Holy people are joyful. Why? Because holiness brings us closer to God, the source of all joy.

W HY AM I SO concerned with joy, humor, and laughter from a spiritual point of view? Why have I written an entire book on the subject? The reaction of those crowds is not the only thing that encouraged me to take up this topic. There was another phenomenon, equally persuasive, that I continually ran across: these virtuesyes, virtues are often sadly lacking in religious institutions and in the ideas that good religious people have about religion.

A little background may be in order. Ive been a Catholic and a Christian my whole life, a Jesuit for over twenty years, and a priest for over ten. So Ive spent a great deal of time living and working among those whom you could call professionally religious. Especially over the last twenty years Ive met men and women working in all manner of religious settingsin churches, synagogues, and mosques; retreat houses, religious high schools, colleges, and universities; rectories, parish houses, and chanceries; parish adult-education programs, interfaith meetings, and religious gatherings of every stripe. And I have known, met, or spoken to thousands of religious people from almost every walk of life. In the process I have come across a surprising number of spiritually aware people who are, in a word, grim.

Not that I expect believers to be grinning idiots every moment of the day. Sadness is a natural and human reaction to tragedy, and many situations in life require, even demand, a serious approach. But Ive met so many religious folks with sour faces that it makes me wonder why they seem to believe that the absence of joy is a necessary part of their spiritual lives.

Many years ago, for example, a friend of mine lived with a Jesuit finishing his doctoral dissertation. One morning, when my friend greeted him, he replied glumly, Please dont talk to me. I dont talk to anyone before lunchtime. My writing is just too stressful, and walked away. But being joy-challenged is not just the province of Jesuit priests and brothers (most of whom are cheerful sorts). Joylessness is nondenominational and interfaith. My minister is such a grump ! a Lutheran friend told me a few months ago, explaining what led her to search for another church. Last year I gave a talk to a large group of Catholics. After the talk someone said approvingly, You know, I actually saw our bishop laugh during your talk. Ive never seen that before. She had been working with the bishop for five years.

A certain element of such joylessness is probably related to personality types; some of us are naturally more cheerful, optimistic, and upbeat. But after encountering the same brand of dejection over and over for twenty years in a wide variety of settings, Ive reached the unscientific (but I think accurate) conclusion that underlying this gloom is a lack of belief in this essential truth: faith leads to joy.

Moreover, this morose spirit has wormed its way into the culture of too many religious institutions. That is, it goes beyond the personal and moves into the communal realm. Why has this happened? A few reasons come to mind.

First of all, our understanding of God is often one of a joyless judge. More about this later in the book, but suffice it to say that when you consider the grim spirit that pervades some church groups, its no surprise that one of the most influential American sermons is Jonathan Edwardss eighteenth-century tract Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God. In it, Edwards thunders, There is no want of power in God to cast wicked men into hell at any moment. Quite an image of Godenough to wipe the smile off any believers face.

Next page