Introduction

MEMORIAL ADDRESS

delivered by Max von Laue

in the Albani Church in Gttingen

on October 7, 1947

My Fellow Mourners:

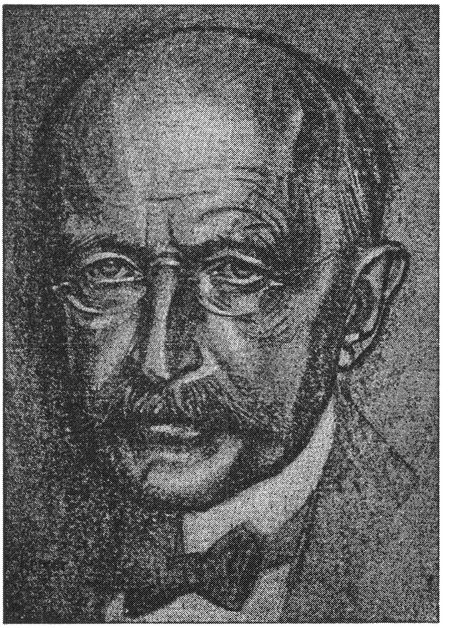

We stand at the bier of a man who lived to be almost four-score-and-ten. Ninety years are a long life, and these particular ninety years were extraordinarily rich in experiences. Max Planck would remember, even in his old age, the sight of Prussian and Austrian troops marching into his native town of Kiel. The birth and meteoric ascent of the German Empire occurred during his lifetime, and so did its total eclipse and ghastly disaster. These events had a most profound effect on Planck in his person, too. His eldest son, Karl, died in action at Verdun in 1916. In the Second World War, his house went up in flames during an air raid. His library, collected throughout a whole long lifetime, disappeared, no one knows where, and the most terrible blow of all fell when his second son, Erwin, lost his life in the rule of terror in January, 1945. While on a lecture tour, Max Planck, himself, was an eye-witness of the destruction of Kassel, and was buried in an air raid shelter for several hours. In the middle of May, 1945, the Americans sent a car to his estate of Rogtz on the Elbe, then a theatre of war, to take him to Gttingen. Now we are taking him to his final resting-place.

In the field of science, too, Plancks lifetime was an epoch of deep-reaching changes. The physical science of our days shows an aspect totally different from that of 1875, when Planck began to devote himself to itand Max Planck is entitled to the lions share in the credit for these changes. And what a wondrous story his life was! Just thinkA boy of seventeen, just graduated from high school, he decided to take up a science which even its most authoritative representative whom he could consult, described as one of mighty meager prospects. As a student, he chose a certain branch of this science, for which even its neighbor sciences had but little regardand even within this particular branch a highly specialized field, in which literally nobody at all had any interest whatever. His first scientific papers were not read even by Helmholtz, Kirchhoff and Clausius, the very men who would have found it easiest to appreciate them. Yet, he continued on his way, obeying an inner call, until he came face to face with a problem which many others before him had tried and failed to solve, a problem for which the very path taken by him turned out to have been the best preparation. Thus, he was able to recognize and to formulate, from measurements of radiations, the law which bears and immortalizes his name for all times. He announced it before the Berlin Physical Society on October 19, 1900. To be sure, the theoretical substantiation of it made it necessary for him to reconsider his views and to fall back on methods of the atom theory, which he had been wont to regard with certain doubts, And beyond that, he had to venture a hypothesis, the audacity of which was not clear at first, to its full extent, to anybody, not even to him. But on December 14, 1900, again before the German Physical Society, he was able to present the theoretic deduction of the law of radiation. This was the birthday of the quantum theory. This achievement will perpetuate his name forever.

This is why on this day innumerable scientific bodies have expressed their sympathy and grief over his death, in telegrams, or by sending their representatives here. Thus, we have with us now the President of the Academy of Berlin, and the Rector of the University of Berlin, two bodies with which Max Planck was especially closely affiliated. He taught at the University for more than forty years, and he was a member of the Academy for more than half a century; in fact, most of that time he held the office of one of its four Permanent Secretaries. Likewise, the Academies of Munich and Gttingen are represented here by their Presidents, the University of Gttingen by its Rector, and the School of Engineering of Hannover by its Faculty delegate. Furthermore, wreaths have been placed on the bier in behalf of the State Government of Lower Saxony.

I would like to mention, in particular, some of the many wreaths lying here. One of them was sent by the German Museum in Munich, which is just about to place Max Plancks bust in its Hall of Fame. Next to the respects paid by the Academy of Munich, this wreath is the last salute from Bavaria, where Planck grew up, and where he would spend his vacation every year, to seek and find pleasure and relaxation.

Another wreath is inscribed: The German Physical Societies to their Honorary Member. These Societies remember the fifty-eight years of Plancks membership, his selfless work in the most diverse administrative posts; for the major part of his membership he was a member of the Board, and also held its chairmanship several times. They remember, in particular, the great many enlightening lectures which he delivered at their scientific meetings, and above all, that address in 1900 when, as mentioned before, he made his first disclosure of his law of radiation and its deduction. A bright ray of his brilliant fame was thus reflected on the German Physical Society, too.

And here is a plainer wreath, without any streamers. It was placed here by me in behalf of all his pupils, among whom I count myself, as a perishable token of our never-ending affection and gratitude.

A Scientific Autobiography

My original decision to devote myself to science was a direct result of the discovery which has never ceased to fill me with enthusiasm since my early youththe comprehension of the far from obvious fact that the laws of human reasoning coincide with the laws governing the sequences of the impressions we receive from the world about us; that, therefore, pure reasoning can enable man to gain an insight into the mechanism of the latter. In this connection, it is of paramount importance that the outside world is something independent from man, something absolute, and the quest for the laws which apply to this absolute appeared to me as the most sublime scientific pursuit in life.

These views were bolstered and furthered by the excellent instruction which I received, through many years, in the Maximilian-Gymnasium in Munich from my mathematics teacher, Hermann Mller, a middle-aged man with a keen mind and a great sense of humor, a past master at the art of making his pupils visualize and understand the meaning of the laws of physics.