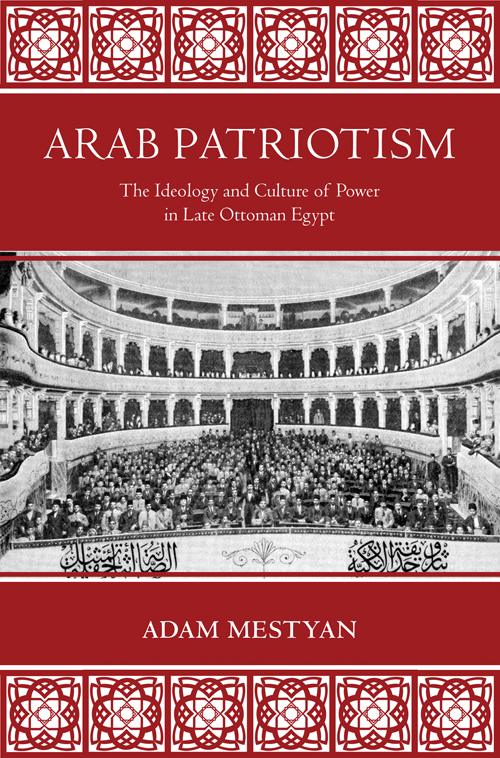

ARAB PATRIOTISM

ARAB PATRIOTISM

T HE I DEOLOGY AND C ULTURE OF P OWER

IN L ATE O TTOMAN E GYPT

Adam Mestyan

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket image: Postcard of the Azbakiya Garden Theater. Courtesy of the Rare Books and Special Collections Library, The American University in Cairo

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-17264-4

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Charis SIL

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

Illustrations

Tables

Notes on Transliteration, Names, Titles, and Currency

Arabic words are transliterated following the system of the International Journal of Middle East Studies (IJMES) without the initial hamza . Colloquial Egyptian Arabic expressions are transcribed according to their pronunciation in todays Cairo. Ottoman Turkish is transliterated according to the modern Turkish alphabet and pronunciation. Arabic or Turkish words found in the Oxford Dictionary of English are used accordingly (Koran, not Qurn ; sheikh, not shaykh ). Muslim months and days are transliterated according to Arabic vocalization, following the IJMES standard ( Rajab and not Turkish Receb or Raceb ; juma , not cuma ).

Where a person gave his or her name in Latin script consistently, I have respected that practice (e.g., Fahmy); however, I have made some exceptions (Khayy, not Kaat; Qard, not Cardahi) to maintain consistency with the earlier literature. In the case of elite Ottomans in Egypt, I transcribe their names according to the Ottoman Turkish conventions (Khedive Ismail, not Isml; Said, not Sad). The names of those, like Isml iddq, who are remembered as Egyptians are transcribed according to the Arabic. Where a military or administrative title has an English equivalent I have used it (Pasha and not Pacha, Paa, or Bsh ; Bey, not Bk ). Efendi, after Ryzova, is written without the double f.

In this period, 1 Egyptian pound ( ghin , LE = livre gyptienne) was 100 piasters ( qirsh/ghirsh , qurush/ghursh ), and 1 piaster was equivalent to 40 paras . Currency exchange rates vary. In 1875, 1 British pound (sovereign) was equivalent to 195 piasters (1.95 LE); 1 French franc was 7 piasters 20 paras. (Murray, A Handbook , 89.) In 1878, 1 French franc was 3.8 piasters (). In 1885, 1 LE was 26 francs ( Baedekers Lower Egypt [1885], 5).

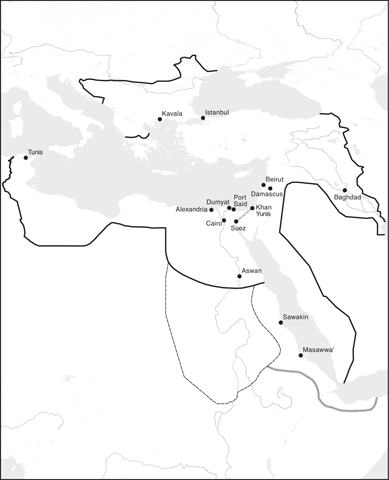

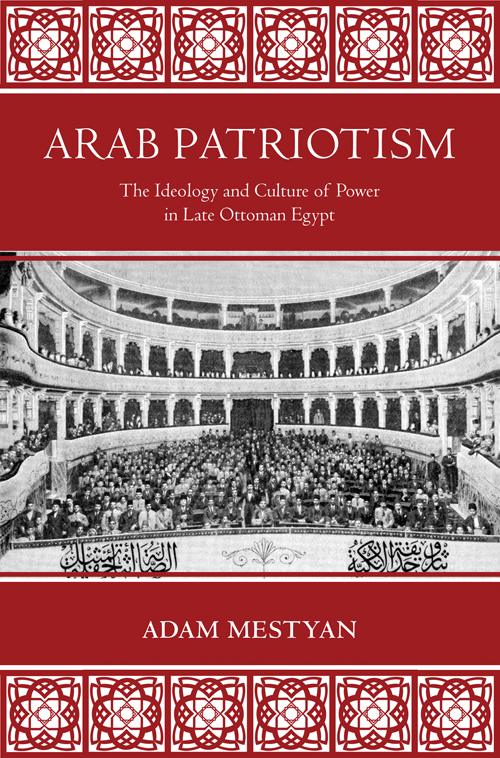

F IGURE I.1. The Ottoman Empire, 1860s

T HE solid black line indicates the approximate boundaries of the Ottoman Empire in the early 1860s. The dashed line indicates the approximate boundaries of the Ottoman-Egyptian sphere of the Sudan after the conquests of Mehmed Ali and his descendants. The double-dashed line indicates the boundary of the Egyptian province in the Sinai according to the 1841 firman. The shaded-dotted line indicates the approximate additions in Africa to Ottoman-Egyptian sphere of interest in the mid-1860s.

Source: Map prepared prepared by Fei Carnes, Harvard Center for Geographical Analysis.

Copyright Fei Carnes.

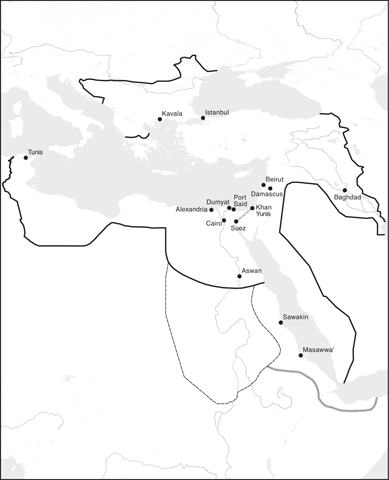

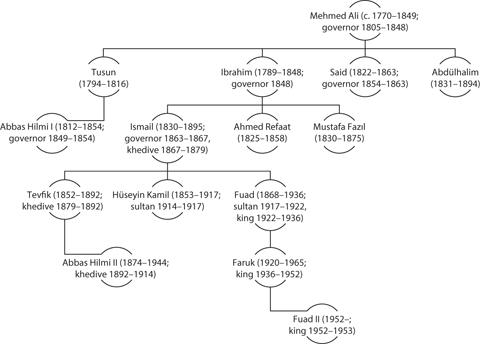

F IGURE I.2. The Rulers of Egypt

ARAB PATRIOTISM

INTRODUCTION

T his book is a study of patriotism in the Egyptian province of the Ottoman Empire. What can we learn by re-examining Egypts nineteenth-century history, not as the tale of progress towards a sovereign nation-state but as the saga of an Ottoman province? What are the consequences of reframing a national narrative in an imperial context?

I argue that the imperial context requires a new theory of national development. The imperial origins of patriotic ideas in provinces complicate standard accounts of how present-day nation-states came to be. Empires provide a fundamentally different structure of political power from that of national settings. The case of the Ottoman Empire is even more complex since the sultans were caliphs of Sunni Islam. Within the imperial system, the ideas and practices specific to provinces reveal the hidden architecture of the empires networks. By retelling Egypts nineteenth-century history as an Ottoman province, we follow the ways in which ideas, practices, and power struggles were enacted and constituted through these networks and imperial hierarchies.

In order to understand this complex story, we have to put aside the standard views of nationalism and religion. In the nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire, including the Egyptian province, two historical trajectories of political thought converged: Muslim concepts of just rule commingled with European notions of homeland framed by a centralizing imperial system. This discursive matrix manifested itself as patriotism . This book offers a new definition of this concept, based on the Ottoman Egyptian example.

Patriotism in Arabic ( waaniyya ) became manifest in two aspects. Firstly, it was an empire-wide ideology of power that provided a tactical vocabulary for Arabic-speaking elites to negotiate co-operation among themselves and with the Ottoman system. In the Egyptian province, it served the goal of achieving a tacit compromise with the semi-independent governor. Secondly, patriotism was a communal emotion, a physical experience of togetherness, constituted in and through public occasions. Such experiences allowed elite and ordinary individuals to imagine themselves as part of a community. Importantly, these were not just any experiences, but experiences that were made possible by new, public practices, institutions, and technologies.

This book, therefore, focuses on performance culture as a key aspect of patriotism. Stages and theater buildings were new public spaces, and going to the theater was a new public ritual in the nineteenth-century Ottoman Arab world. Arabic journalism and theater were intertwined enterprises and together built up a fragile public sphere. Arabic musical theater was connected to patriotism in Arabic journals. Prewritten musical plays performed on stages, involving women, in front of a seated audience, were innovations that creatively absorbed earlier practices like Arabic poetry, singing, and popular mimetic performances. Language was made compatible with the new spaces. The study of performance culture is crucial to understand what being public , hence being a patriot , meant in the changing Ottoman urban world.

Moreover, plays provide access to plural, often opposing, definitions about what exactly the community of the homeland is. Plays were written by learned and talented individuals; and their ideas often served political and business interests. Plays could also function as petitions. In general, during a performance, ideas are translated into experience and, vice versa , experience influences ideas. Plays, their performances, and reception can convey the change in the realm of subversive ideas before such change manifests itself in political action, but plays can also represent and serve official doctrine. Importantly, entertainment and journalism are commercial enterprises, and so the practices of patriotism also illuminate the history of Arab capitalism. Not only local or global but also imperial factors influenced the content, staging, and reception of plays. The Ottoman Egyptian elites, as we shall see, instrumentalized Western European opera for their own representation. Arab Patriotism therefore demonstrates the impure construction of nation-ness in the black box of culture.

Next page