Richard Killeen - A Short History of Dublin

Here you can read online Richard Killeen - A Short History of Dublin full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Gill & Macmillan, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

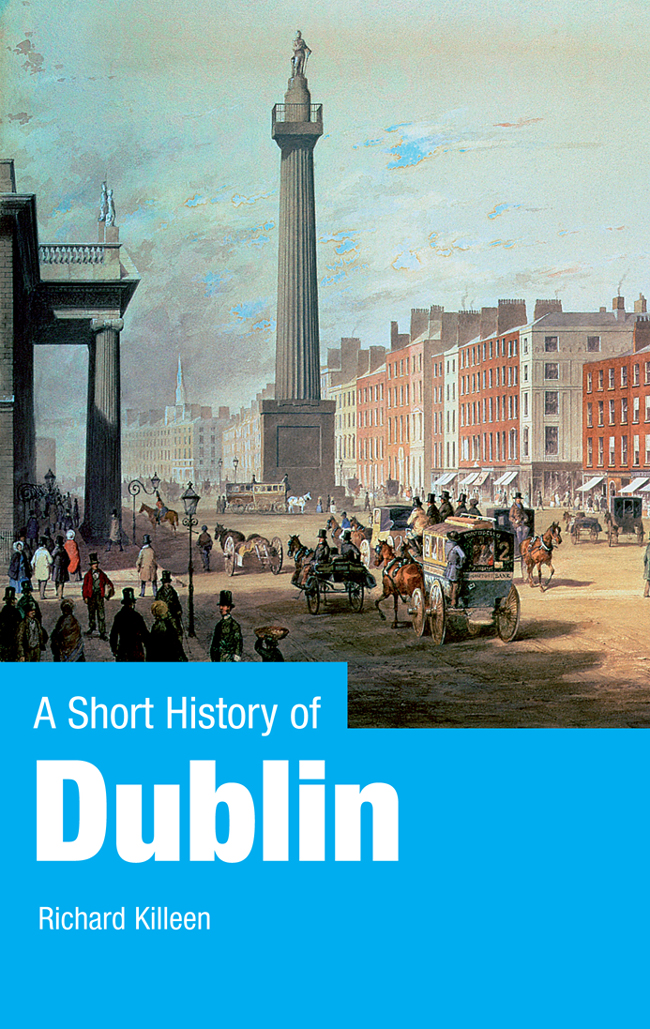

- Book:A Short History of Dublin

- Author:

- Publisher:Gill & Macmillan

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Short History of Dublin: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Short History of Dublin" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Short History of Dublin — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Short History of Dublin" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

A SHORT

HISTORY OF

DUBLIN

RICHARD KILLEEN

Gill & Macmillan

Contents

RIVERRUN |

D ublin wraps around a C-shaped bay, but it offers no natural deep-water harbour. The bay is shallow and tidal with a series of treacherous sandbars. None the less, the bay is the widest potential refuge for shipping on the east coast of Ireland. It is fed by a modest river, the Liffey, but one which is navigable at high water. It also commands the shortest sea crossing to Britain carrying shipping to north Wales and to the estuaries of the Mersey and the Dee, thus giving access to the rich middle and south of England.

In Roman times, the imperial outpost of Chester at the mouth of the Dee was the most significant port in north-west England. It is only a half-truth to state that the Romans never came to Ireland. There have been many archaeological finds of Roman coins and artefacts on the east coast, proof of commerce and intercourse between Roman Britain and the smaller island. The connection between Chester and Dublin endured for centuries. The patron saint of Chester in early Christian times, Werburgh, is commemorated in a prominent parish church in central Dublin, just a stones throw from Christ Church Cathedral.

The mouth of the Liffey afforded easy access to the Irish midlands. Due west, there are few natural obstacles to the progress of immigrants, settlers and invaders. While the same might be said of the mouth of the River Boyne, about forty kilometres to the northwhose valley holds the richest evidence of prehistoric settlement on the islandthe river itself offers no harbour or bay to compare with Dublin.

The only other location that might have challenged the Liffey was Waterford at the south-east corner of the island, with its magnificent three-river estuary offering shipping an unrivalled safe haven. However, its most direct cross-channel passage carried you to west Wales, a region of stubborn remoteness, impervious over the centuries to settlement by Romans, Vikings, Normans, the English and the rest of the world generally. Waterford was in time to develop into an important port, but it never offered a serious challenge to Dublin for overall primacy.

Dublin offered a series of advantages, therefore, which in aggregate made it the most plausible location for a significant east-coast settlement. The origins of the first settlers are long lost to history, but it appears that the landward side was as important as the seaward in this process. At Church Street Bridge, a natural ford allowed passage across the river at low tide. From this point, a series of ancient roads penetrated to the interior. The ford itself was prone to inundation at spring tides and storms, so a sturdier artificial ford was constructed slightly upstream. This was the Ford of the Hurdles or, in Irish, tha Cliath, from which the modern city takes its name in that language: Baile tha Cliath, the town of the ford of the hurdles. These fords were a necessity, for the business of crossing the river was fraught with hazard. Over 700 members of a military raiding party are recorded as having drowned in the attempt in the eighth century.

Modern Dubliners are accustomed to the embanked river being contained behind its quay walls from Heuston Station to the sea. The embanking of the river began in Viking times, as the town gradually became a centre of trade and commerce, but for centuries it was a haphazard process. In its natural state, the watercourse covered a much greater area than today. It is only possible to speculate on its exact course, but it can be reconstructed with reasonable confidence.

On the north bank, the probable course of the river seems to have roughly followed the modern boundary as far east as the present Capel Street bridge, before gradually spreading to cover what is now the lower reaches of OConnell Street. On the south side, however, a much more dramatic effect was created in what is now Parliament Street, the southern end of Temple Bar and the City Hall area. Here, a huge pool delivered the waters of the Poddle, a tributary whose course was later to wrap itself around the southern and eastern walls of Dublin Castle, into the Liffey. All the modern streets and places just mentioned stand on land reclaimed from this triangular Poddle pool. The dark waters of this pool bore the Irish name Dubh Linn, which in time came to denote the whole district to the east of the Poddle confluence, while the area to the west retained the older name of tha Cliath. The eastern settlement was principally the site of religious houses; the older, western one was mainly secular in purpose. Of the two Irish-language names, it was Dubh Linn that was eventually anglicised to give the city its name.

There was evidence of settlement around the bay from Mesolithic times, more so from the later Neolithic period. Still, this takes us back to about 4000 BCE. The Celts, who first irrupt into Ireland around 250 BCE, also appear to have had some sort of settlement on the rising ground above the ford close to Christ Church. This was the obvious location for a settlement, being contiguous to the fordand therefore to the system of roads and trading routesand defensible. This also became the focus of the Viking and Norman towns.

Ptolemys map of the second century CE shows Ireland as a triangular island to the west of Britain, with a settlement about half way along the east coast called Eblana. This is the earliest cartographical acknowledgment of Dublin. There has been a great deal of scholarly dispute about this claim, but it seems that there was a settlement of sufficient significance in this region to come to the notice of Ptolemy in faraway Alexandria. On the logic of the discussion above, any such settlement was most likely to have been found around the shores of Dublin Bay.

Whatever its nature, the settlement never developed the sinews of a town in any sense that modern people could acknowledge. That had to await the arrival of the Vikings, with whom the history of the city proper may be said to begin.

BEGINNINGS: THE VIKING TOWN |

T he term Viking refers to groups of Scandinavian people from two principal regions: the south and west coasts of Norway and the Jutland peninsula to the south across the Skagerrak. These people, in possession of their lands from ancient times, had originally migrated across the Great Northern Plain of Europe, which offered few natural obstacles to such migration.

Quite what impelled the Vikings to their sudden, violent and energetic expansion overseas from the eighth century CE is uncertain. There may have been population pressures, which would have been particularly severe in Norway with its rocky coastal valleys trapped and surrounded by impassable mountains on the landward side. The combination of limited and poor land together with the unforgiving northern climate would have made such habitats especially vulnerable to population growth, with any surplus population impelled to shift for itself. The gradual development of the proto-kingdoms of Norway and Denmark in the early Viking period may also have caused tribal groups alienated from the move towards centralised kingdoms to seek their fortunes elsewhere.

Whatever the reasons, the facts are incontrovertible. The Vikings developed the finest fleet of seafaring craft in contemporary Europe, which carried them to Britain and Ireland, north-west France, and as far east as Novgorod in Russia. The first Viking raid on Britain occurred in 789, but the most dramatic early assault was on the holy island and monastery of Lindisfarne in Northumbria.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Short History of Dublin»

Look at similar books to A Short History of Dublin. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Short History of Dublin and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.