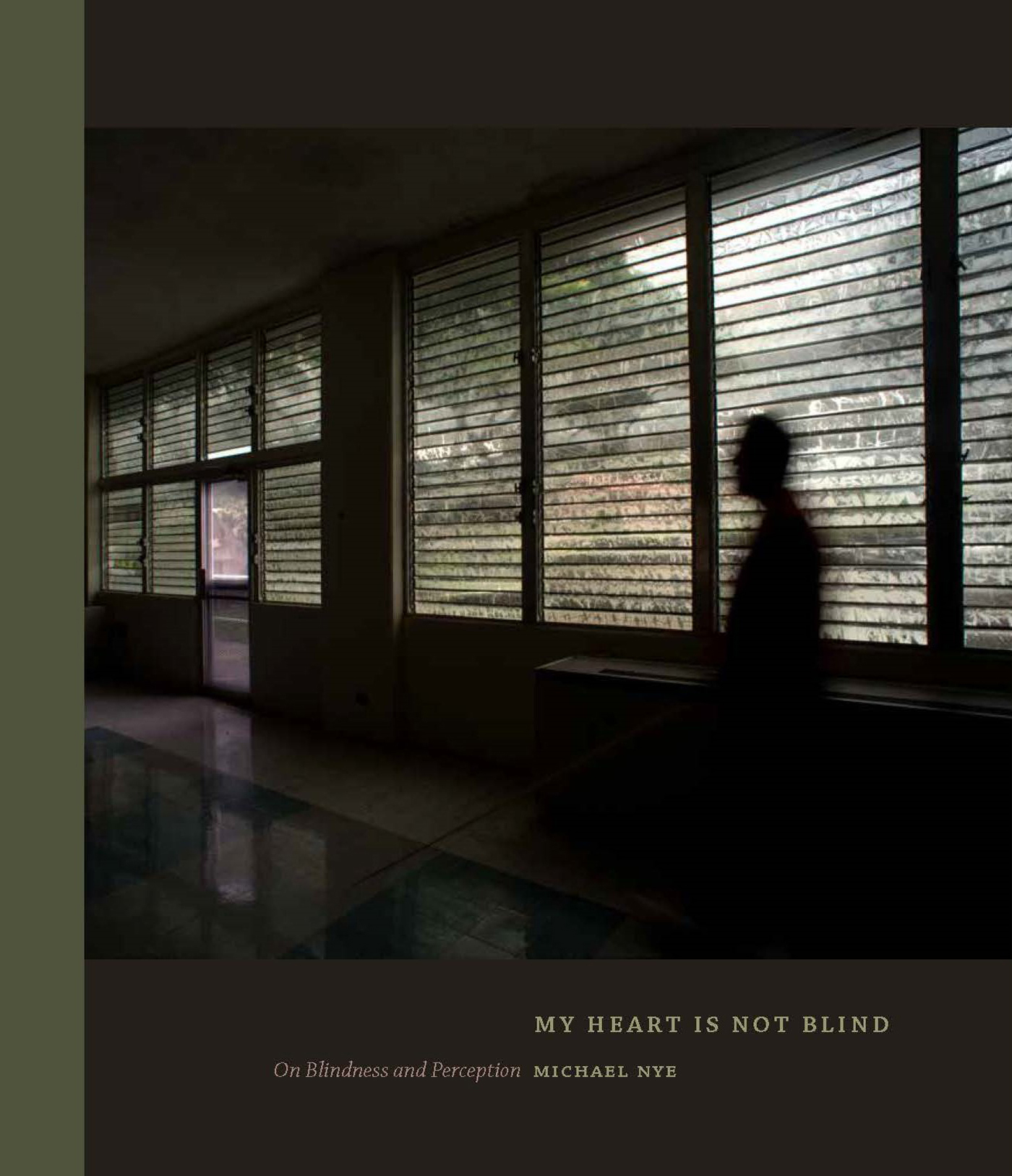

MY HEART IS NOT BLIND

MY HEART IS NOT BLIND

On Blindness and PerceptionMICHAEL NYE

TRINITY UNIVERSITY PRESSSan Antonio, Texas

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Not all blind people are blind. Not all sighted people can see. Knowing what the world looks like is not a requirement for understanding. For many, blindness suggests a lack of awareness. If that is true, then everyone is blind to what they dont know.

I had a photography exhibition in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, thirty years ago. I was asked to give a gallery talk to a group of international blind students. What I remember visually was their intense gaze and resolute attention. With them, a whisper traveled far. I tried to describe the difference between early light and twilightthat black-and-white photography could represent less than or more than what was experienced in ways that might amplify visual perception. Their questions were straightforward and profound. Why are you a photographer? What is beautiful that is nonvisual? What is the meaning of these photographs? How can anyone, blind or sighted, understand the world outside themselves? It was the students who were giving the gallery talk, and I was listening.

I began to think about the deep well of perception and attention. It is attention that strengthens connections of neurons and allows us to remember. It is attention that can lead us out of our private lives into the wider world and lives of others. It is attention that pushes us, protects us, and creates expertise. It is attention that can unearth what is necessary, important, and hidden. What did these students understand about our human experience as a result of their attention and reliance on their other senses, especially relating to touch and sound?

When I returned home I arranged meetings with a group of blind individuals and sighted visual artists (poets, sculptors, photographers, and painters). We had conversations about awareness and perception. We talked about metaphor, articulation of light, echolocation, three-dimensional visualization, the deeper meaning of voice, touch, and the intuition of space and time. Everyone, blind and sighted, came away excited, carrying new and revised vocabularies.

Over the last seven years I have been listening to men and women who are blind or visually impaired. I spent two to three days with each person. Its been a rare privilege to have these deep and personal conversations. My ears saw much more than my eyes. This project is about blindness and perception, but it is also about human adaptation. It is about a grave misunderstanding of the nature of blindness. It is about what we have in common, and the fragility that is a part of our shared human condition. No one I met wanted to feel or be insignificant. Everyone I met talked about the notion of giving, and a hunger to know and do more.

The first individual I interviewed was Larry Johnson. He is tall, thin, bearing a contagiously deep radio voice. He lost his vision as a baby due to infantile glaucoma. When he speaks, his voice rises with enthusiasm. He spent twenty-two years working as a top DJ in Mexico. Larry is a teacher, a writer of compelling op-ed pieces, and tireless encourager to many. He is fascinated by the powers of observation and the challenges of lifes puzzles. I interviewed him in his home. Inside it was extremely dark. I stumbled against walls and furniture. At the same time, Larry was dashing around his house, answering his phone, heating up tacos, making coffee, and helping me plug in my recorder. Who was in a position of advantage?

Jacques Lusseyran (19241971) became blind in an accident at the age of seven. He became a leader in the French resistance movement fighting the Nazis in 1942. In his moving memoir, And There Was Light, he writes about his adaptation to his changed condition: People often say that blindness sharpens hearing, but I dont think this is so. My ears were hearing no better, but I was making better use of them. Sight is a miraculous instrument offering us all the riches of physical life. But we get nothing in this world without paying for it, and in return for all the benefits that sight brings we are forced to give up others whose existence we dont even suspect. These were the gifts I received in such abundance.

Blindness is not what the public thinks it is. It is something very different. It doesnt diminish someones cognitive or emotional abilities. Vision races, whereas touch, sound, taste, and smell are slower, more deliberate. Eyes are greedy. Vision examines surfaces, where sound and touch are more intimate. The public fears blindness in the same way they fear cancer or dementia. For many, darkness and the unknown are deeply frightening. Whenever I hear any sighted person speak of blindness, it is always about inabilities or limitations. The conversations are rarely about competency or newfound perspectives. When something is taken away, often something else takes its place.

Generalizations fall apart along the edges. Stories about blindness are not stories about darkness. Every persons particular vision loss or impairment is acutely unique to their adaptation and life experience. Being born blind is nothing like losing sight in middle or old age. Losing vision slowly due to a genetic eye disease is nothing like losing vision in a moment. The first year of blindness is very different than long-term developed nonvisual adaptation. Living with shame, without support, is very different than being surrounded by encouragement with the expectations of education and independence.

Visual impairment (having some vision or light sensation) is also inexplicably complex. Terms such as legally blind, moderate or severe low vision, and near blindness are used to describe degrees of impairment. For many, visual impairment is like living between two unfriendly worlds. Natalie said, It feels like being inside a slowly constricting narrow tunnel on a foggy day. I might see a fly on the wall across the room and trip over an elephant getting to it.

There are so many ways eyesight can be lost or impaired or damaged. Some of the diseases and causes in this project include retinopathy of prematurity, brain aneurysm, Peters anomaly, car bomb, detached retinas, scarlet fever, Charles Bonnet syndrome, cone and rod dystrophy, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, septo-optic dysplasia, train accident/collision, Lebers hereditary optic neuropathy, Lebers congenital amaurosis, cancer of the retinas, gunshot, retinitis pigmentosa, diabetic retinopathy, choroideremia, spinal meningitis, hereditary glaucoma, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, narrow- and open-angle glaucoma, cortical blindness, infantile congenital glaucoma, osteoporosis-pseudoglioma syndrome, and macular degeneration.

The diversity of impairment to vision further emphasizes the divergent experiences and nonvisual adaptation. Every story carries a point of view, and the simple awareness of it is enough to make it rare and valuable.

Each person I met has been intensely tested. Most who lost eyesight after having vision went through an initial period of depression and desperation. Language seems so inadequate to describe such early seasons of despair.

I was first in denial then fury. I tore apart my mattress and bed frame, and I did this by hand.

Losing your sight is like being shotnot in your heart but in your soul. I asked God for mercy. I cried every day.

How can I live? How was I going to be the same person I was before?

Yet many others, including Richard, had very different responses: He was driving home from work and was hit by a train. The glass exploded and took out his eyes. The way I adjusted to my blindness was that I had a family and two small children who depended on me. My worry was how was I going to support them? he said. So I jumped right into mobility training, trying to find out how do things being blind. I started repairing automobiles as a blind man simply because I did that when I was sighted.

Next page