I propose to consider the question, Can machines think?

Alan Turing (1950)

It is not my aim to surprise or shock you but [] there are now in the world machines that think, that learn and that create. Moreover, their ability to do these things is going to increase rapidly until in a visible future the range of problems they can handle will be coextensive with the range to which the human mind has been applied.

Herb Simon (1958)

[T]he first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make []

I. J. Good (1965)

[W]orkers in artificial intelligence blinded by their early success [] will settle for nothing short of the moon. [] To persist in such optimism in the face of recent developments borders on self-delusion.

Hubert Dreyfus (1965)

No one in 2015 would dream of buying a machine without common sense, any more than anyone today would buy a personal computer that couldnt run spreadsheets, word processing programs, communications software, and so on.

Doug Lenat (1990)

The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race.

Stephen Hawking (2014)

Acknowledgements

Felicity Bryan and Rowland White made this delightful project possible, for which I am enormously grateful. Heartfelt thanks to Sarah Baldwin, Tony Cohn, Will Hutton, Suzanna Marsh, Graham May, Steve New, Andr Nilsen, James Paulin, Andre Stern, Rowland Stout, Jordan Summers-Young, and Kiri Walden, who provided feedback on drafts of the book.

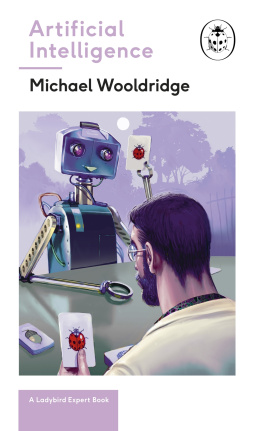

Series 117

This is a Ladybird Expert book, one of a series of titles for an adult readership. Written by some of the leading lights and outstanding communicators in their fields and published by one of the most trusted and well-loved names in books, the Ladybird Expert series provides clear, accessible and authoritative introductions, informed by expert opinion, to key subjects drawn from science, history and culture.

Every effort has been made to ensure images are correctly attributed; however, if any omission or error has been made please notify the Publisher for correction in future editions.

MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Text copyright Michael Wooldridge, 2018

All images copyright Ladybird Books Ltd, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

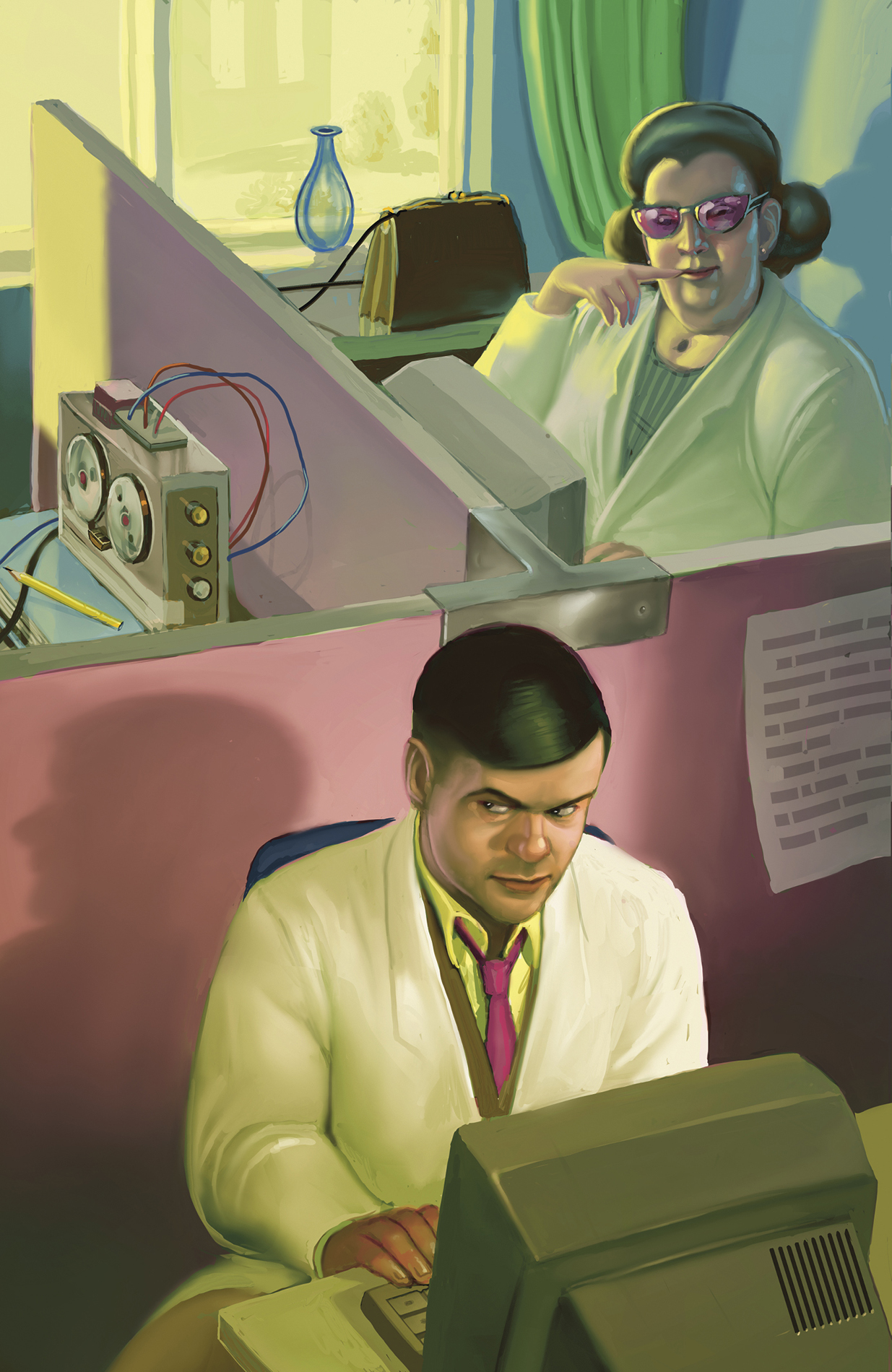

Colour illustration by Stephen Player

ISBN: 978-1-405-93418-3

Michael Wooldridge

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

with illustrations by

Stephen Player

The idea of AI

We all know something about Artificial Intelligence (AI). From the deadly computer HAL-9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey to the accommodating robot hosts of Westworld, countless movies, novels and computer games have enthralled us and sometimes terrified us with the prospect of conscious, self-aware, intelligent machines.

But AI is not just science fiction. Since the first computers were developed in the 1950s, AI has been an active scientific discipline, and many developments in modern computing in fact trace their origins to AI research. There have been genuine breakthroughs recently that would have astonished the early AI pioneers. But AI has a notorious track record for overselling itself. All too often, AI researchers have let their excitement and optimism lead to wildly unrealistic predictions of what they were going to achieve. The history of AI is full of ideas that initially showed promise, but which, in the end, didnt work as hoped. Because of this, many people are sceptical about AI.

The reality of AI today what has been achieved, and what might be possible is tremendously exciting, but it is far removed from the AI of science fiction. In this book, we will explore what AI really is. Starting from its origins, we will examine the various ideas that have shaped the field, taking us to the present day, when AI systems are all around us. We will then look at where AI might ultimately take us.

The Turing test

One of the first scientists to think seriously about the possibility of AI was the brilliant British mathematician Alan Turing. To all intents and purposes, Turing invented computers in the 1930s, and soon after became fascinated by the idea that computers might one day be intelligent. In 1950, he published a scientific paper on the question of whether a machine could think. The paper introduced the :

You are interacting via a computer keyboard and screen with something that is either another person or a computer program. The interaction is in the form of text questions and answers. Your task is to determine whether the thing being interrogated is in fact a person. Now suppose, after some time, you cannot tell whether the thing is a person or program. Then, Turing argued, you should accept that the thing being interrogated has human-like intelligence.

Turings genius was to see that the test sidesteps issues such as how the program is doing what it is doing: anything that passes the test is doing something indistinguishable from human behaviour.

Ingenious as it is, Turings test has limitations. For one thing, it looks only at one narrow aspect of intelligence. Also, it is possible to write programs that use cheap tricks to confuse the interrogator (this is what Internet chatbots do these are not AI). Contemporary AI researchers have developed refined versions of Turings test, which are resistant to such trickery.

The Chinese Room

Many people have argued that machines can never really be conscious or self-aware. One argument is that there is something inherently special about people. It is hard to rebut this claim, but also hard to accept it: ultimately, people are just atoms bumping into each other. A more sophisticated argument against the possibility of AI was proposed by the philosopher John Searle. His Chinese Room scenario supposedly demonstrates that machines cannot have understanding:

Imagine a room in which a man, who understands no Chinese, receives, through a slot in the door, questions written in Chinese. When he receives a question, the man carefully follows detailed instructions written in English to generate a response to the question, which he passes back out through the slot. Now suppose the questions and responses are part of a Chinese Turing test, and the test is passed.

Here, the man plays the role of a computer the instructions he follows to generate a response are the program. Searle argued that there is no understanding of Chinese anywhere here: the man doesnt understand, and the instructions surely dont. So, there is no understanding.

Next page