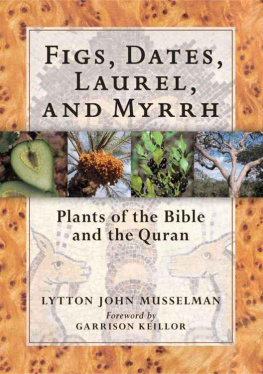

Figs, Dates, Laurel, and Myrrh

Figs, Dates, Laurel, and Myrrh

Plants of the Bible and the Quran

LYTTON JOHN MUSSELMAN

foreword by

GARRISON KEILLOR

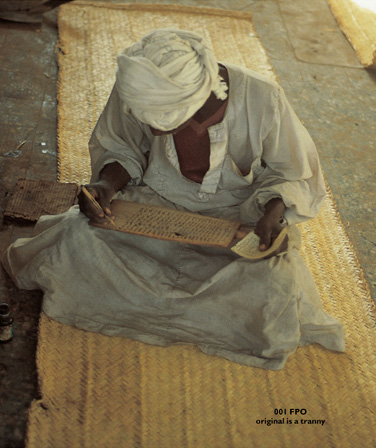

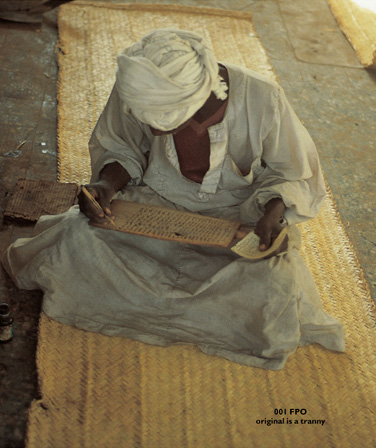

Frontispiece: A Sudanese man using a board from acacia to copy verses from a collection of praises. His inkpot, on his right, contains a mixture of charcoal, gum arabic, and other products. After the board is filled, the writing is washed off so the board can be used again.

Facts stated in this book are to the best of the authors knowledge true, but the author and publisher can take no responsibility for the misidentification of plants by the users of this book nor for any illness that might result from their consumption. If there is any doubt whatsoever about the identity or edibility of a plant, do not eat it.

Photographs are by the author unless otherwise indicated.

Copyright 2007 by Lytton John Musselman.

All rights reserved.

Published in 2007 by

Timber Press, Inc.

The Haseltine Building

133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450

Portland, Oregon 97204-3527, U.S.A.

www.timberpress.com

For contact information regarding editorial, marketing, sales, and distribution in the United Kingdom, see www.timberpress.co.uk.

Printed in China

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Musselman, Lytton J.

Figs, dates, laurel, and myrhh: plants of the Bible and the Quran/Lytton John Musselman; foreword by Garrison Keillor.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-88192-855-6

1. Plants in the Bible. 2. Plants in the Koran. I. Title.

BS665.M87 2007

220.8058dc22 2007019025

A catalog record for this book is also available from the British Library.

Solo Deo Gloria

Contents

Apricot tree laden with fruit in June, near Deir Attaya, Syria

Foreword

IN THE BIBLE PICTURE BOOKS of my childhood, the Holy Land was an arid plain with some mountains in the distance. Men in turbans and robes rode their grim-faced camels toward an oasis of palm trees. Here and there, men toiled in vineyards, and when it was time for Jesus to be crucified, he went to the Mount of Olives. But mostly scripture was without much vegetation, so far as our picture books were concerned. There were the green pastures, of course, and the lilies, and the Song of Solomon was dripping with plants and fervid feeling and your neck is like a tower of David and your breasts like two small rabbits and references to thighs, but by and large, Canaan did not seem so pleasant or promising. In Bethlehem and Jerusalem and Nazareth, houses were jammed in tight on narrow streets, no lawns or shrubs, so unlike 14th Avenue South in Minneapolis where I attended Sunday School at the Grace & Truth Gospel Hall, where stately elms made a solid canopy over the pavement and lush grass grew and nearby was Powderhorn Park where we tossed a softball around between Bible Reading at 3 p.m. and Gospel Meeting at 7:30.

We were Plymouth Brethren and we were rather arid ourselves, if the truth be told, more like cactuses than fruit trees. Our bunch was a little band of 50 Christians who stuck to their guns though reduced by painful schisms and dominated by an alpha male, an engineer, a stubborn German who ran a tight ship. They clung to their belief in the literal truth of scripture, the priesthood of all believers, the silence of women, services conducted according to the leading of the Spirit, communion reserved for those in tight agreement on doctrineand every year there were more empty seats in their midst. The young people kept defecting, going over the wall to the Baptists and Presbyterians, trying to escape that aridness, that sense of decline in the air. The Brethren accepted decline as more or less inevitable, even as a sign of their own faithfulness. (Many are called, but few are chosen.) They did not expect showers of blessing or a great flowering or a magnificent harvest, not here, not in this life. They hunkered in the dust and prayed for endurance.

Scripture speaks of pastures and vineyards and wheat fields but I did not envision these in my Christian imagination. The idea of the gospel as a seed was lost on me. (It was more like a precious jewel that had been given to us and that we kept locked in a box.) Mine was an indoor faith, under a roof, with many empty seats and a dogged orthodoxy that was more like a fortress than a garden. Our pope was J. N. Darby, the father of the Brethren movement, who had been dead for years and so his dicta could not be questioned. He was a separatist and so we were separated too. We were like a tiny ghetto.

My father probably felt otherwise about all of this, he being a farm boy and a passionate gardener. We lived on an acre lot north of Minneapolis along the Mississippi River and grew tomatoes, beans, corn, cucumbers, melons, strawberries, spinach, squash, and peas to feed six growing children. I did not inherit his love of plants and I had a habit of sneaking away from garden chores and hiding in a ravine, a lovely overgrown creek bed, and lounging around under the sumac and red oaks and imagining myself a Union spy behind Confederate lines. The trees themselves did not interest me. They were only a backdrop. I have maintained my ignorance of botany to the present day, and that is why Lytton Musselman asked me to write a foreword: he knew it was the only way to get me to read the book.

Friend Musselmans book is shocking to me. Here is a distinguished American botanist with years of research experience in the Middle East pointing at the picture book I still carry in my mind and saying, It was not an apple that Eve gave to Adam. It may have been an apricot. It sure was not an apple. This is a jolt to an old believer like me. I can accept that the lilies (Consider the lilies of the field) may have been anemones and that the tree Zaccheus climbed was not our sycamore and that the rose of Sharon may have been a gladiolus or that the willows they hung their harps in may have been poplars. Nor does it trouble me that the mustard seed of the parable might have been arugula. Except your faith be like unto the arugulathat is going to go over well with the Episcopalians.

Until I read Musselmans book, I did not know what myrrh is. I am sixty-four and a college graduate but if a child had asked me, What is myrrh? I would have been forced to lie. The name, my dear, comes from polymer, it was an early plastic formed as a byproduct when they burned rubber plants, and it was considered quite precious, and thats why the Wise Men brought it as a gift for the Christ Child, so He could form it into a ball in his tiny hand and bounce it on the floor. Wrong. It is the dried resin of several species of shrubs in the genus Commiphora. You get this resin by squeezing commas and if you sniff it you become euphoric.

Balm of Gilead is likewise a resin, from the terebinth tree, not just a line in a hymn. I love a fact like this, though terebinth trees have never loomed large in my life, nor has saffron. Nonetheless it is good to know that 75,000 saffron flowers are needed to produce the threads to make one pound (454 grams) of the spice. Your thighs shelter a paradise of pomegranates with rare spices, sang Solomon, and one of those spices was saffron. (Cinnamon and aloe too. Check it out the next time youre in the vicinity of a thigh.)

Next page