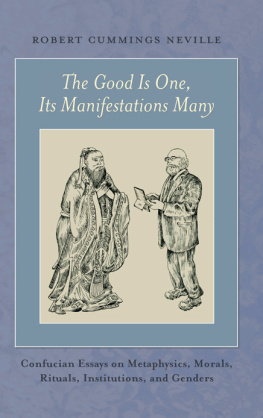

The Good Is One, Its Manifestations Many

ROBERT CUMMINGS NEVILLE

The Good Is One, Its Manifestations Many

C ONFUCIAN E SSAYS ON M ETAPHYSICS , M ORALS , R ITUALS , I NSTITUTIONS, AND G ENDERS

State University of New York Press

Published by

S TATE U NIVERSITY OF N EW Y ORK P RESS , A LBANY

2016 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact

S TATE U NIVERSITY OF N EW Y ORK P RESS , A LBANY , NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Laurie D. Searl

Marketing, Anne M. Valentine

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Neville, Robert C., author.

Title: The good is one, its manifestations many : Confucian essays on metaphysics, morals, rituals, institutions, and genders / Robert Cummings Neville.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016007752 (print) | LCCN 2016035068 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438463414 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438463438 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Philosophy, Confucian21st century.

Classification: LCC B5233.C6 N46 2016 (print) | LCC B5233.C6 (ebook) | DDC 181/.112dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016007752

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Roger T. Ames, Cheng Chung-ying, and Tu Wei-ming Friends, Mentors, Colleagues

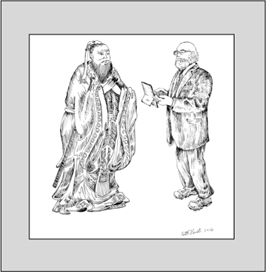

The art of the cover of this volume is by Beth Neville, my wife, who has prepared art for many of my book covers. I thank her once again for doing this, with a line drawing this time. Her image is a humorous reference to me as a slightly quaint Boston Confucian. On the left is a stereotypical drawing of Confucius, taken from a number of sources and modified by her style. On the right is a drawing of me in a suit in which I often teach, but wearing sneakers. Im holding my brand-new mini-laptop and seem to be taking notes from Master Kung. Let no one think, however, that I intend to channel Confucius, any more than he intended in fact to channel the great sage emperors, however much he feigned doing so tongue in cheek. My intent in this book is to nudge contemporary Confucianism in new directions. Thanks to Beth for seeing the irony in this.

Contents

Preface

Just before our plane landed in Korea on our first visit to East Asia, my wife, Beth, told me, Robert, Im not going to walk eight paces behind you, and your Confucian friends will just have to cope. Such is the reputation of Confucianism for the demeaning of women even in its contemporary expressions. For several years, I have taught courses at Boston University on theological issues of gender identity. Many of our students from China and Korea cringe at what they take to be the bigotry of their home cultures, particularly their home church cultures, and they blame the bigotry on the legacy of Confucianism (even among East Asian Christians). The feminist womens movement and the LGBTQ revolution have been powerfully effective worldwide, particularly among intellectuals, although their practical success in combating the varieties of bigotry they oppose varies widely.

Contemporary Confucians have been slow to address this issue face-on, much to the chagrin of women studying Chinese philosophy from the perspective of feminism. Perhaps this is because of two themes that seem to be necessary default positions for Confucianism. One is the emphasis on fulfilling family responsibilities, modeling many other interpersonal relations on familial ways of showing humaneness. A second is the importance of exercising humaneness through the mature playing of rituals that define individuals in part through ritual roles. These two themes seem to set up Confucianism for devastating criticisms from those who emphasize the social construction of gender identities and roles, pointing out how unfair and hurtful many of those social constructions are.

In this collection of essays, I aim to show a way forward for contemporary Confucians, of whom I am one. Of course, I am not only a Confucian. Confucians working in Boston (and many other Western environments) live in cultures where some significant protections of women and sexual minorities are already written into law, even if far more still remains to be done.

To be fair historically, I doubt that Confucianism through the ages has been any worse on women and sexual minorities than most other religious or philosophical cultures. It seems that African Islam and some tribal religions today are about as hard on those groups as any culture has ever been. Most feminist and gender liberation movements in the last century or so have been directed against abusive bigotry in Christianity and Judaism. Although there have been saintly mothers in Buddhisms and Hinduisms, the lineages of authority often have been through males. I have never heard of a female Dalai Lama or Gyalwa Karmapa. Ancient Advaita Vedanta says that reincarnation is a comfort because you might have to wait many lives until you are born a male Brahmin, which is required in order to attain enlightenment and nirvana. The living heirs of all these cultures and religious traditions need to address the issues of bigotry related to gender identities. My concern here, however, is to build a Confucian response that addresses gender bigotry in all cultures, not only those in which Confucianism has been deeply formative for centuries.

Most of the time when these gender issues are raised, it is from the side of the liberationist critics who look at what Confucianism has to say about them. This inevitably brings up a reductionist vision of Confucianism, leaving out what does not pertain to gender and often expressing moral edginess regarding Confucian suppression of women. My approach here is the opposite: to attempt to develop a healthy and systematic contemporary version of Confucianism first and then to address the gender issues. Hence, the chapter devoted explicitly to the intellectual and practical issues of gender identity and respect is at the very end of the book. It is as if the first fourteen chapters are devoted to getting contemporary Confucianism ready to address feminist critiques, which is done only at the end and in a cursory way. This book is not a systematic feminist critique or a set of specific detailed instructions about how Confucianism ought to change its historical rituals so as to be more respectful of women (and sexual minorities). Many of the intervening chapters raise pertinent issues about gender, but the strands of argument are brought together only at the end. The reason for this order is that there are many themes in contemporary Confucianism that need to be addressed beforehand if a Confucian position is to be presented properly as a global philosophy with wisdom about the nature of gender identities and what to do to liberate them socially and politically.

By Confucianism here I mean the many streams of philosophy that relate back positively to Confucius and that have been called Confucian or Ruist. I dont mean to suggest that these traditions are always fair to Confucius or are consistent with one another. Different periods of Confucian thought have existed and have interacted significantly with Buddhist and Daoist ideas and practices. Philosophies are significant, among other ways, by how they direct personal, social, and cultural life, and Confucianism has influenced these practical domains quite differently in different times and social contexts. A more elaborate discussion of the definition of Confucianism in is