27.

Foreword by His Holiness the Dalai Lama

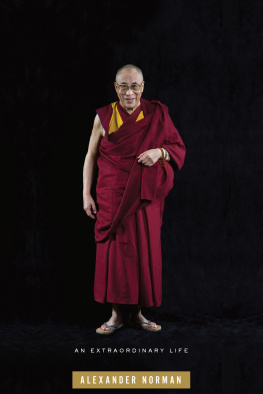

Foreword by His Holiness the Dalai LamaIn this book, Alex Norman, an old personal friend, offers a distinctive outsiders view of the history and culture of Tibet. In particular, he brings out the human element in telling the story of the institution of the Dalai Lamas. He has gone to a great deal of trouble to explain how this lineage, commonly associated with Avalokitesvara or Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva embodying compassion, is traditionally traced back to an ancient Indian origin and then how it later developed in Tibet. He shows too how it evolved from being a purely spiritual institution into one that also became deeply involved with the political and cultural life of the country.

While Alex looks unflinchingly at the relative turmoil that characterizes important episodes in Tibetan history, his narrative also shows how Tibetan religious culture developed into a system that faithfully preserves the most complete form of the Indo-Buddhist tradition extant in the world today. It is a tradition derived principally from the great Indian university of Nalanda. At the same time, he shows how Tibets relationship with her formidable neighbor, China, has existed for well over a thousand years. In the beginning, during the time of the Tang dynasty, this relationship was one of equality. A relationship of personal equality also obtained between the Dalai Lamas and both the Mongol and later the Manchu Emperors of China.

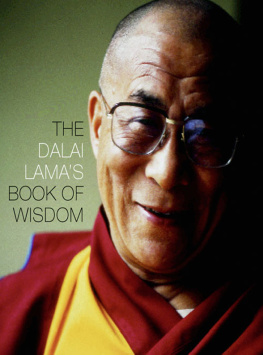

The fourteen individuals who have carried the title of Dalai Lama naturally display quite a range of difference between their personalities. From the gentle and compassionate Gendun Drub, the first Dalai Lama, through the great scholar and teacher, Gendun Gyatso, his successor, to the visionary Great Fifth in the seventeenth century right up to my immediate predecessor the Great Thirteenth, who worked so hard for the cause of Tibetan independence, and then to my own case, each has quite clearly exhibited different personal characteristics. Nevertheless, in the Tibetan mind, there is also a close association between Chenrezig and the Dalai Lamas, which reflects a longstanding special relationship between the Tibetan people and Chenrezig. Tibetans have a special admiration and faith in Chenrezig because his unfathomable compassion naturally extends to all sentient beings without limit or partiality. He shows by example that qualities such as love, compassion, and the altruistic mind of enlightenment are like a jewel that overcomes the poverty and difficulties of cyclic existence, while at the same time fulfilling the wishes of all sentient beings. When Chenrezig is referred to as Holder of the White Lotus, the lotus denotes wisdom, and while there are various kinds of wisdom, such as an appreciation of impermanence and a lack of self-sufficient existence, the main one is the wisdom realizing emptiness.

This book narrates the life story of each of the Dalai Lamas, situating them in the context of their time. In so doing, it tackles many difficult and sensitive issues within Tibetan history, many of which raise important questions. While I do not necessarily agree with every opinion the author has expressed, I very much appreciate the frankness he brings to bear in his analysis of these matters.

Alex Norman is an English gentleman, who, despite our different backgrounds, has been a good friend to me and has helped me in several ways for which I remain grateful. I commend this book to anyone wishing to deepen their knowledge of Tibetan history and culture. It contains insights which, I am sure, will be illuminating even to experts in the field.

March 2008

Acknowledgments

It is my privilege first to thank Tenzin Gyatso, Fourteenth Dalai Lama of Tibet, for lending his support to this project from the outset. He did so in spite of my warning that I intended to tackle several of the most delicate and controversial aspects of Tibetan history. I take it that, by placing his confidence in me in this way, the Dalai Lama was honoring an association anddare I say ita friendship that began more than twenty years ago. In the intervening period, it has been my good fortune to work closely with him on two of his more important books as well as to collaborate with the Dalai Lama on several other projects, both spiritual and secular. I desire, therefore, to thank His Holiness for the extraordinary level of trust he has shown me.

Ippolito Desideri, the great Jesuit missionary in Tibet, records the hospitality he was shown by a people he found clever, kindly, and courteous by nature. I cannot improve on those remarks. I would like, however, to mention a number of people who have offered me the same great courtesy and kindness as was Father Desideri almost three centuries ago. These are Mr. Tendzin Choegyal and his wife Mrs. Rindchen Khandro, Kasur Tenzin Geyche Tethong, and Dr. Thupten Jinpa Langri, academic adviser to His Holiness and his principal translator into English. Each in their different ways has contributed enormously to my understanding of Tibetan history and culture. I am especially grateful to Dr. Langri, not only for his friendship over all these years but also for his scholarly advice during the research of this book and for his unflagging readiness to help during its writing and editing. He was, furthermore, a most attentive and perceptive reader of the final manuscript. I doubt that I would have undertaken the work had I not been able to rely on his encyclopedic knowledge of Tibetan literature and his deep familiarity with both Tibetan Buddhist and Western philosophical thought. All this is not to mention his personal generosity.

Among the community of Tibetan scholars, I have been kindly assisted by Mr. Tsering Dhondup Gongkatsang of Oxford University, especially in the matter of translation. Professor Samten Karmay responded readily to several requests for assistance. Geshe Lobsang Jhorden [Lhakdorla] has, over the years, favored me with a great deal of his time. In the UK, Dr. Charles Ramble, university lecturer in the Department of Tibetan and Himalayan Studies at Oxford University, not only made available to me the full resources of his department but also put me in touch with several of the scholars I mention here. And in connection with Oxfords Bodleian Library, I would like to thank Ralf Kramer who, as Librarian of the Indian Institutes Tibetan collection, responded enthusiastically to literally hundreds of requests for assistance.

I was most fortunate to have Professor Don Lopez read the final draft of my manuscript. Not only did he make many useful suggestions, he also saved me from a number of embarrassing mistakes. Those that remain are mine alone. I would also like to acknowledge with gratitude the answers given to specific questions by Professor Paul Williams, Dr. John Peacock, E. Gene Smith, Professor Morris Rossabi and Dr. Susan Whitfield. For his translation from the Russian of Petr Kozlov, I would like to thank Mark Belcher. I have also received much patient assistance from Mike Gilmour of Wisdom Books; also from David Chilton of Taikoo Books, who enabled me to track down many elusive titles. I am fortunate to be able to count among my friends and acquaintance the following four distinguished writers: Patrick French (author of the matchless