T O J ESSICA R OSE

Contents

Guide

Acknowledgements

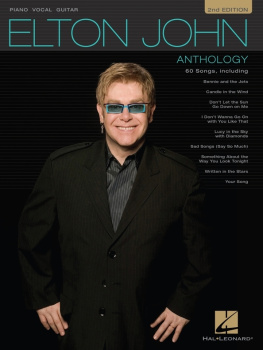

Thanks are due to Rolling Stone for permission to quote from their interview with Elton John.

PROLOGUE

Goodbye, Englands Rose

Westminster Abbey, London, 6 September, 1997

T HROUGHOUT Elton Johns career there have been times when his natural politeness and humility have given way to outbursts of infantile temper known as Eltons Little Moments. But his life is far more notable for Big Moments, when he has risen further and still further above the attitudes and aspirations usually expected of a pop star. We are about to see Eltons Biggest Moment ever.

For six days the nation has been in shock. Diana, Princess of Wales is dead killed along with her Arab playboy lover Dodi Fayed when their chauffeur-driven car crashed in a Parisian underpass while apparently fleeing from paparazzi. Now, on a Saturday as golden as her hair, as balmy as her smile, she is to be laid to rest. In death, even more than in life, she will present Britain with some of the strangest, most unsettling scenes it has witnessed in this or any century.

Diana made royalty even more of a spectacle than Elton John made rock music. Before she came along in 1981, Britains Royal Family received almost no media coverage outside the plodding, dowdy routine of state ceremonial and overseas tours. Thirty years ago, who could have imagined royalty transformed into an endlessly mesmerising romance-cum-tragedy-cum-farce that would make the behemoths of pop culture seem dull and predictable by comparison? In 1995, the surviving Beatles announced the reunion for which billions had waited almost a quarter of a century, with Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr overdubbing accompaniment on some lost vocal tracks by John Lennon. Alas, its release happened to coincide with the BBC Panorama interview in which Diana exposed the sham of her fairy-tale marriage and gave her husband, the future king, a flaying of such subtlety as had not been seen since the Spanish Inquisition. In competition with that, even the Beatles Second Coming was doomed to be an also-ran.

Now she has gone, which means she is more ubiquitous than ever, filling every TV screen with that 18-carat mop, those sky-blue eyes, that oddly asymmetric nose, those long legs, that halting, childish voice, and all those endlessly contradictory phases of her sixteen years in the spotlight. Here is the creamy-faced bride under a virginal veil... the Eighties sloane in frills and Laura Ashley prints... the fun mum, plunging down theme park water-chutes and sprinting without her shoes on school sports days... the sumptuous fashion-plate dressed by Versace and Lacroix... the angel visitant, unafraid to pick up a maimed African child or cuddle an AIDS sufferer... the effortless beauty who looked her most sensational after being drenched with rain during Pavarottis Hyde Park concert... the worrier about her own supposed physical defects, who exercised obsessively and forbade photographers to shoot her in profile... the exquisitely tailored, lonely figure on a bench in front of the Taj Mahal, palpably wishing for a husband whod love her a millionth as much... the hater of media intrusion who couldnt live without cameras... the shopaholic, the hysteric, the bulimic... the helpless, the cunning... the classy, the vulgar... the crassly foolish, the idiotically brave... the totem of shrink-speak and victim culture... the exploiter even of her own children in pursuit of public affection... the campaigner against landmines... the unhealthily fascinated observer at surgical operations...

For these all too human flaws as well as her near-divine radiance the world came to love Diana as no star, certainly no princess, was ever loved before. Only those who remember the death of King George VI, forty-six years ago, have seen public grief on such a scale in Britain. People cling together and weep in a way familiar among warm-blooded European races but hitherto anathematised by chill, reserved Anglo-Saxons. People of all ages, all classes, all ethnic origins, cling and weep. Some of it is for the benefit of hysteria-hungry television crews, all of it may be the result of watching too much Oprah Winfrey and Jerry Springer, but it is undeniably, overwhelmingly, sincere. At Kensington Palace, Dianas former London home, the floral tributes left at the gate have become a plastic-wrapped ocean that almost fills the surrounding park. Queues stand patiently, day and night, to sign the books of condolence.

In the suicide-rush of her life, she made the House of Windsor wobble. With her death, she rocks it to its very foundations. The Prince of Wales stands condemned long since as a cold, selfish twit whose rejection of his adoring young bride and inexplicable preference for his weatherbeaten mistress, Camilla Parker Bowles, have cast grave doubts on his fitness to inherit the throne. Throughout various unbecoming imbroglios that have beset the Royal Family over the years, the Queen herself has always remained immune from criticism. But no more. There is audible anger that in the days following the accident she and Prince Philip remained sequestered at Balmoral, their Scottish estate, offering no word of grief for their former daughter-in-law or of sympathy toward their stricken subjects. The new Prime Minister, Tony Blair, is forced to intercede, like Disraeli with the reclusive Queen Victoria 150 years earlier, persuading his sovereign to appear on television and pay tribute to Diana, however grimly, from my heart.

The funeral is an uneasy compromise between the will of the people and the ill-will of the establishment. Multitudes line a two-mile processional route from Kensington Palace to Westminster Abbey; massed television cameras wait to beam the event to a worldwide audience calculated at 2.5 billion. But the full military honours of a state funeral are withheld. The corteg consists of a single antique cannon and horse-drawn limber from the Royal Horse Artillerys Kings Troop whose gold-braided gunners fire ceremonial salutes on royal birthdays. The gun bears Dianas coffin, an artefact weighing 40 stone, wrapped in a Union Jack and topped by a spray of lilies. Her sons, William and Harry, walk behind, Victorian-style, with their father, grandfather and uncle. There is eerie quiet, broken only by the rhythmic tolling of a bell, the jingle of horse harness, shrieks of un-British anguish from the onlookers and, bizarrely, periodic bursts of clapping.

Inside the abbey, things get even heavier. Dianas brother, the young Earl Spencer, rails at the monarchic chilliness and insensitivity he holds responsible for hounding her to her fate, and pledges that her blood family will be the one to shelter and nurture her boys. It is as if a gauntlet is being flung down in some Shakespearian tragedy. The Queen sits, frozen-faced, watching the dynasty she has worked so long to maintain being pilloried in the very place where, forty-four years ago, she received her sacred anointing and had the crown lowered on to her head. At this moment, there is only one Queen of England and her name is not Elizabeth. Despite the muffling thickness of the abbeys thousand-year-old walls, the crowds outside somehow sense what is happening. Every new lance thrust by the hot-headed earl unleashes further distant bursts of applause.

There is perhaps only one person alive who can save the day. He rises from among the massed VIPs, a familiar stocky figure wrapped in a plain dark suit of ultimate cost, his puggy features set in a resolute frown, his eyes masked by tinted glasses that on this occasion are doubly needful. As he walks towards the grand piano specially placed in the abbey nave, a moment that was unreal beyond conception becomes like so many others back through the chaotic decades to his childhood in Pinner, Middlesex. A voice whispers in his ear as irresistibly as when he was a resigned but dutiful eight- or nine-year-old and it was his mother speaking. Come on, its up to you... Theyre waiting... You cant let them down... Be a good boy.