WAR BABY

I was never really wanted.

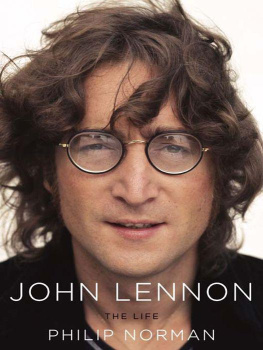

J ohn Lennon was born with a gift for music and comedy that would carry him further from his roots than he ever dreamed possible. As a young man, he was lured away from the British Isles by the seemingly boundless glamour and opportunity to be found across the Atlantic. He achieved that rare feat for a British performer of taking American music to the Americans and playing it as convincingly as any homegrown practitioner, or even more so. For several years, his group toured the country, delighting audiences in city after city with their garish suits, funny hair, and contagiously happy grins.

This, of course, was not Beatle John Lennon but his namesake paternal grandfather, more commonly known as Jack, born in 1855. Lennon is an Irish surnamefrom OLeannain or OLonainand Jack habitually gave his birthplace as Dublin, though there is evidence that his family had already crossed the Irish Sea to become part of Liverpools extensive Hibernian community some time previously. He began his working life as a clerk, but in the 1880s followed a common impulse among his compatriots and emigrated to New York. Whereas the city turned other immigrant Irishmen into laborers or police officers, Jack wound up as a member of Andrew Robertons Colored Operatic Kentucky Minstrels.

However brief or casual his involvement, this made him part of the first transatlantic popular music industry. American minstrel troupes, in which white men blackened their faces, put on outsize collars and stripey pantaloons, and sang sentimental choruses about the Swanee River, coons, and darkies, were hugely popular in the late nineteenth century, both as performers and creators of hit songs. When Robertons Colored Operatic Kentucky Minstrels toured Ireland in 1897, the Limerick Chronicle called them the worlds acknowledged masters of refined minstrelsy, while the Dublin Chronicle thought them the best it had ever seen. A contemporary handbook records that the troupe was about thirty-strong, that it featured some genuinely black artistes among the cosmetic ones, and that it made a specialty of parading through the streets of every town where it was to appear.

For this John Lennon, unlike the grandson he would never see, music did not bring worldwide fame but was merely an exotic interlude, most details of which were never known to his descendants. Around the turn of the century, he came off the road for good, returned to Liverpool, and resumed his old life as a clerk, this time with the Booth shipping line. With him came his daughter, Mary, only child of a first marriage that had not survived his temporary immersion in burnt-cork makeup, banjo music, and applause.

When Mary left him to work in domestic service, a solitary old age seemed in prospect for Jack. His remedy was to marry his housekeeper, a young Liverpool Irishwoman with the happily coincidental name of Mary Maguire. Although twenty years his junior, and illiterate, Marybetter known as Pollyproved an ideal Victorian wife, practical, hardworking, and selfless. Their home was a tiny terrace house in Copperfield Street, Toxteth, a part of the city nicknamed Dickens Land, so numerous were the streets named after Dickens characters. Rather like Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield , Jack sometimes talked about returning to his former life as a minstrel and earning fortunes enough for his young wife, as he put it, to be farting against silk. But from here on, his music making would be confined to local pubs and his own family circle.

Jacks marriage to Polly gave him a second family of eight children. Two died in infancy, a fact that the superstitious Polly attributed to their Catholic baptism. The next six therefore received Protestant christenings, and all survived: five boys, George, Herbert, Sydney, Alfred, and Charles, and a girl, Edith. Polly did a heroic job of feeding them all on Jacks modest wage. But their diet of mainly bread, margarine, strong tea, and lobscousea meat-and-biscuit stew from which Liverpudlians acquired the nickname Scouseswas chronically lacking in essential nutrients. This had its worst effect on the fourth boy, Alfred, born in 1912, who as a toddler developed rickets that stunted the growth of his legs. The only remedy known to pediatrics in those days was to encase both of them in iron braces, hoping the ponderous extra weight would promote growth and strength. Despite years burdened by the braces, Alfs legs remained puny and foreshortened, and he failed to grow any taller than five feet four inches. He was, even so, a good-looking lad, with luxuriant dark hair, merry eyes, and the distinctive Lennon family nose, a thin, plunging beak with sharply defined clefts over the nostrils.

Jacks musical talents were passed on to his children in varying measure. George, Herbert, Sydney, Charles, and Edith all had passable singing voices, and the boys played mouth organ, the only instrument young people in their circumstances could afford. Alf, however, showed ability of an altogether higher order, allied to what his brother Charlie (born in 1918) called that show-off spirit. He could sing all the music-hall and light operatic songs that made up the World War I hit parade; he could recite ballads, tell jokes, and do impressions. His specialty was Charlie Chaplin, the anarchic little tramp whose film comedies had created the unprecedented phenomenon of an entertainer famous all over the world. At family gatherings, Alf would sit on his fathers knee in his Tiny Tim leg irons, and the two would sing Ave Maria together, with sentimental tears streaming down their faces.

Jack died from liver disease, probably caused by alcoholism, in 1921. Unable to survive on the state widows allowance of five shillings per child per week, Polly had no choice but to take in washing. It meant backbreaking, hand-scalding work from four a.m. to dusk, scrubbing other peoples soiled linen on a washboard, then squeezing out the sodden coils through a heavy iron mangle. Even so, as her granddaughter Joyce Lennon remembers, the cramped little house remained always spotless with floors you could eat your dinner from, the kitchen range cleaned with graphite religiously every Monday morning, the front step scoured almost white, then edged in red with a chip of sandstone. Polly ruled her five sons like Mrs. Joe in Great Expectations , not hesitating to chastise them with a leather strap even when they were nearly grown men. Like many Liverpudlians of the most down-to-earth kind, she had her mystical side, believing herself a psychic, able to read the future in spread-out playing cards or the pattern of tea leaves in an empty cup.