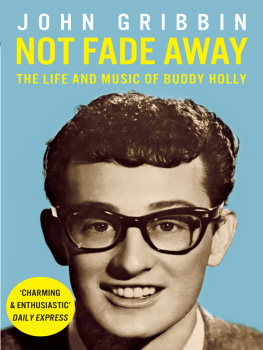

P HILIP N ORMAN

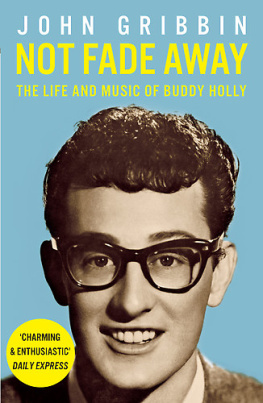

Buddy

The Definitive Biography of

BUDDY HOLLY

PAN BOOKS

To the Lailey family, Trevor, Anne, Anne-Marie and Suzannah.

Good companions on the road to Lubbock.

C ONTENTS

Prologue

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

Part Four

Epilogue

L IST OF I LLUSTRATIONS

Prologue

L ISTEN TO M E

B UDDY H OLLY is buried almost within sight of the modest street where he was born in Lubbock, Texas. Despite the thousands who have come to visit his grave these past thirty-seven years, no tour-buses run to it; there are no sonorous-voiced guides, no Disney-style working models nor souvenir stalls. His home city may have been slow to recognize his enormous fame, but at least that has prevented any hint of the tacky opportunism with which Elvis Presley is memorialized at Graceland. In death, as in his brief life, Buddy remains untainted by vulgarity.

Those who would do him homage must make their own way by rented car from the new Civic Center where he is belatedly commemorated by a lanky bronze statue and a Walk of Fame. You drive past the La Quinta Inn along Avenue Q, make a right on to 4th Street, then another right on to Martin Luther King Jr Boulevard, which Buddy knew as Quirt Avenue. Beyond the railroad-tracks, in a desolate hinterland of granary yards and container-depots, is Lubbocks municipal cemetery. It is wholly typical of this star of uttermost magnitude that his last resting-place should be on public land, accessible to any and every visitor.

Lubbock cemetery is a pleasant place, tranquil and understated in a way which seems hardly Texan yet somehow evokes the spirit of Buddy everywhere you look. In defiance of year-round sun, the interconnecting lawns are a fresh spring green. The memorials are unpretentious and set generously wide apart. Small trees lend dappling shade to vases and pots whose flowers are regularly replenished and arranged with loving care. The only noise is the steady roar of a neighbouring grain-silo, as huge and sombrely magnificent as a medieval cathedral. Beside one newly turfed hillock, a little black and white dog keeps vigil with its nose resting miserably on its front paws. Its air of baffled disbelief that a much-loved voice could be extinguished with such cruel suddenness is doubly appropriate here.

A female clerk in the nearby administration office points out the Holly grave with a courteous smile, despite the wearisome familiarity of the inquiry. It lies barely 100 yards from the main gate, beside a dusty roadway where the cars of one or two latercoming mourners are usually parked. There is no fancy memorial, not even an upright stone just a simple oblong of granite, embedded in the stubby grass. The red dust that blows from the cottonfields, winter and summer, has illuminated the letters of the inscription in dusky orange. This commemorates Buddy under the surname he was born with and would have kept throughout his life had not a typing mistake on his first recording contract decided otherwise:

In loving memory

of our own

Buddy Holley

September 7, 1936

February 3, 1959

To the right of the inscription is a bas-relief of a Fender Stratocaster guitar, that once-astonishing two-horned silhouette, set about by musical notes and holly-leaves. Across the guitars granite contours lie a scatter of small coins like so many extra volume-knobs in pristine silver and copper. It has become a tradition that the fans who find their way here from all over the world leave behind good-luck tokens of nickels and new-minted pennies, as well as red carnations, plastic toy crickets, childrens drawings of Buddy and pairs of black horn-rimmed spectacles in case there should be no oculists in Heaven.

In the distance, the grain-silo temporarily abates its roar, turning up the volume of birdsong. The sad little dog still lies and waits for a voice that can never come. The sun glances off the scatter of nickels and pennies, transforming them to brilliant treasure under the giant Texan sky whose stillness now might be of conscious remembrance.

On a basis of simply counting heads, rock music surpasses even film as the most influential art form of the twentieth century. By that reckoning, there is a case for calling Buddy Holly the centurys most influential musician.

Elvis Presley and he are the two seminal figures of fifties rock n roll, the place where modern rock culture began. Virtually everything we hear on record or tape and see on video or the concert stage can be traced back to those twin towering icons Elvis with his drape jacket, sideburns, pout and swivelling hips; Buddy in big black glasses and buttoned-up Ivy League jacket, brooding over the fretboard of his Fender Stratocaster.

But there is no question as to whom posterity owes the greater debt. Presleys place in rock n roll is no more than that of a gorgeous transient; having unleashed it on the world, he soon forsook it for slow ballads and schlock movie musicals. Holly by contrast was a pioneer and a revolutionary; a multidimensional talent which arrived fully-formed in a medium still largely defined by fumbling amateurs. In the few hectic months of his heyday, between 1957 and 1959, he threw back the boundaries of rock n roll, gave substance to its shivery shadow, transformed it from a chaotic cul-de-sac to an highway of infinite possibility and promise. To call someone who died aged twenty-two the father of rock is not as incongruous as it might seem. What has always set his persona apart from others in the rock n roll pantheon is its air of maturity, sympathy and understanding. To successive generations of fans he has seemed less like an idol than a teacher, guide and friend; a buddy in every sense of that unassuming yet so-comforting word.

The songs he wrote and performed are classics of rock n roll; two-minute masterpieces that remain as fresh and potent today as when they were recorded going on forty years ago. Thatll Be The Day, Peggy Sue, Oh Boy, Rave On the titles have become synonyms for a drape-suited, pink-Cadillac belle poque which we have come regard almost with the same misty-eyed nostalgia as the golden years of Hollywood.

His voice is the most imitated, yet imitable, in rock music. Dozens of other singers down the decades have borrowed its inflection and eccentricities of pronunciation and phrasing. None has ever exactly caught the curious lustre of its tone, its erratic swings from dark to light, from exuberant snarl to tender sigh, nor quite brought off the famous hiccupy catches of breath with which he could fracture even the word Well into six stuttering syllables. It was a voice able effortlessly to run the whole gamut of pop, from rock n roll in maximum overdrive to thoughtful love songs whose warm intimacy stays in bloom year after year. As I write this, in London on 6 March 1995, the radio is playing a commercial for Home Comfort garden conservatories and storm windows. The jingle is a breath-for-breath copy of Buddy singing Everyday: as usual, like him yet nothing like him.

One crucial detail above all sets him apart from Presley and the other primal rock genii. Whereas they had all become solo performers by the time they burst on the world, Buddy Holly came to stardom fronting a group, the Crickets, whose guitar/bass/drums line-up was the protype of every rock band there has been or will be. Unlike Presley and other guitar-toting idols of the period, he was a gifted player, responsible for most of the luminous guitar breaks that became a hallmark of his records. His playing-style is as widely copied as his voice the moody drama he could conjure from a shifting sequence of four basic chords, his incisive downstrokes and rhythm-lead solos. The deification of the rock guitarist, the enduring sex-appeal of the solid-body guitar, the pre-eminence of the Fender make: all were set in train, on the stage of the New York Paramount and the London Palladium, by Buddy and his sunburst Stratocaster.