PLATO

Julia Annas

New York / London

www.sterlingpublishing.com

STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

Published by arrangement with Oxford University Press, Inc.

2003 by Julia Annas

Illustrated edition published in 2009 by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Additional text 2009 Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Distributed in Canada by Sterling Publishing

c/o Canadian Manda Group, 165 Dufferin Street

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6K 3H6

Book design: The DesignWorks Group

Please see picture credits on page 175 for image copyright information.

Manufactured in the United States of America

All rights reserved

Sterling ISBN 978-1-4027-7052-4

For information about custom editions, special sales, premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales Department at 800-805-5489 or .

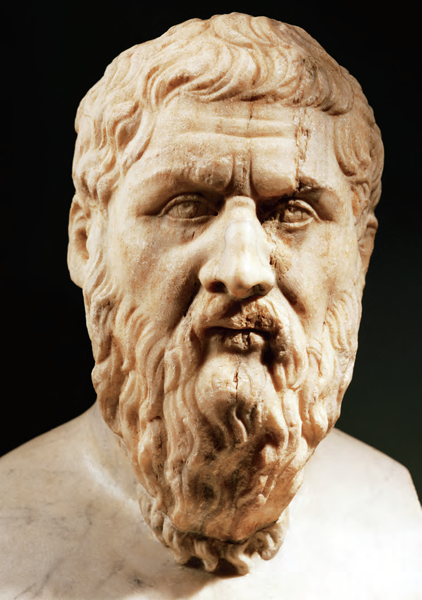

Frontispiece: Bust of Plato

CONTENTS

In reading Plato, it is important to pay attention to the role of argument. This undated mural painting by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes showing Plato conversing with a student at the Academy hangs in the Boston Public Library.

The Jurys Problem

Imagine that you are on a jury, listening to Smith describe how he was set upon and robbed. The details are striking, the account hangs together, and you are completely convinced; you believe that Smith was the victim of a violent crime. This is a true belief; Smith was, in fact, attacked.

Do you know that Smith was attacked? This might at first seem like an odd thing to worry about. What better evidence could you have? But you might reflect that this is, after all, a courtroom, and that Smith is making a case which his alleged attacker will then try to counter. Can you be sure that you are convinced because Smith is telling the truth, or might it be the way the case is being presented that is persuading you? If it is the latter, then you might be worried; for then you might have been convinced even if Smith had not been telling the truth. Besides, even if he is telling the truth, is his evidence conclusive as to his being attacked? For all you know, he might have been part of a setup, and its not as though you had been there and seen it for yourself. And so it can seem quite natural to conclude that you dont actually know that Smith was attacked, though you have a belief about it which is true, and no actual reason to doubt its truth.

THE THEAETETUS

The Theaetetus is one of Platos most appealing dialogues, but also one of his most puzzling. In it, Socrates says that he is a midwife like his mother: he draws ideas out of people, before testing them to see whether they hold up to reasoned examination. Refusing to put forward his own ideas about what knowledge is (though displaying sophisticated awareness of the work of other philosophers), he shows faults in all of the accounts of knowledge suggested by young Theaetetus. Pursuing the thought that if you know something, you cant be wrong, Theaetetus suggests that knowing might be perceiving; then having a true belief; then, having a true belief and being able to defend or give an account of it. All these suggestions fail, and the dialogue leaves us better off only in awareness of our own inability to sustain an account of knowing. Socrates insistence on arguing only against the positions of others, not for any position of his own, made the dialogue a key one for the Platonic tradition which took Platos inheritance to be one of seeking truth by questioning those who claim to have it (as Socrates often does in the dialogues) rather than by making his own philosophical claims. Others, noting that in other dialogues we find positive, ambitious claims about the nature of knowledge, thought of the Theaetetus as clearing away only accounts of knowledge that Plato took to be mistaken. Socrates here, the midwife of others ideas who has no children of his own, seems very different from the Socrates of other dialogues such as the Republic, who puts forward positive ideas quite confidently. Readers have to come to their own conclusions about this (some ancient and modern solutions are discussed in ).

In the Theaetetus, rather than espousing and supporting with philosophical argument his own idea of what knowledge is, Socrates simply refutes the many attempts of the young Theaetetus to define knowledge. Socrates is shown here discussing a philosophical premise with two pupils in a manuscript from the first half of the thirteenth century.

The Areopagus (Hill of Ares), the original four-hundred-member supreme tribunal of Athens (later increased to 501 members), is believed to have met in the open air on this rocky hill in Athens.

In his dialogue Theaetetus Plato raises this issue. What can knowledge be, young Theaetetus asks, other than true belief? After all, if you have a true belief you are not making any mistakes. But Theaetetus is talking to Socrates (of whom more in ) and, as often, the older man finds a problem. For persuading people in public is something that can be skillfully done. He means the skill of what we would call lawyers, although he is talking about a system in which there are no professional lawyers. The victim had to present his own case, though many people hired professional speechwriters, especially since they had to convince a jury of not 12 but 501 members.

HOW WE REFER TO PLATOS WORKS

In 1578 the publisher Henri Etienne, the Latin form of whose surname is Stephanus, produced the first printed edition of Platos works in Paris. The new technology enabled a much greater number of people than hitherto to read Plato. And for the first time it became possible to refer precisely to passages within dialogues, since readers were for the first time using the same pagination. We still refer to the page on which the passage appeared in Stephanuss edition (for example, 200), together with one of the letters

Next page