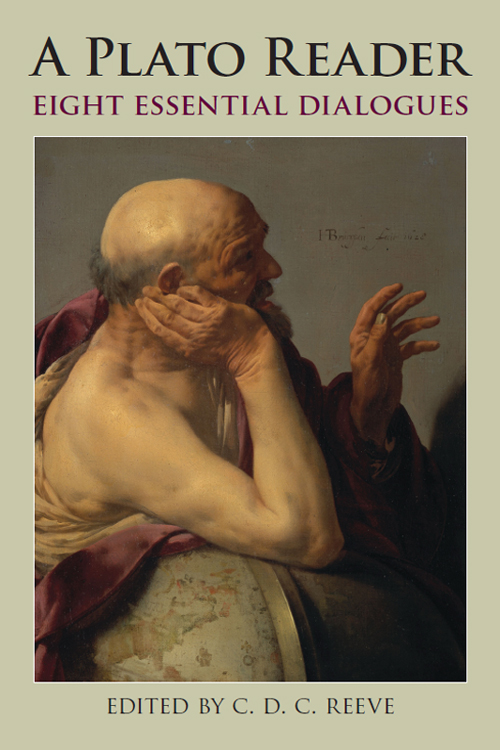

A PLATO READER

A PLATO READER

Eight Essential Dialogues

E UTHYPHRO

A POLOGY

C RITO

M ENO

P HAEDO

S YMPOSIUM

P HAEDRUS

R EPUBLIC

Edited by

C. D. C. Reeve

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2012 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

16 15 14 13 12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

For further information, please address:

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, IN 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Brian Rak

Text design by Meera Dash

Composition by William Hartman

Printed at Data Reproductions Corporation

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Plato.

[Dialogues. English. Selections]

A Plato reader : eight essential dialogues / edited by

C.D.C. Reeve.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).

ISBN 978-1-60384-811-4 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-60384-812-1 (cloth)

I. Reeve, C. D. C., 1948 II. Title.

B358.R45 2012

184dc23

2012013057

ePub ISBN: 978-1-60384-965-4

Plato was born in Athens in 429 BCE and died there in 348347. His father, Ariston, traced his ancestry to Codrus, who was supposedly king of Athens in the eleventh century BCE; his mother, Perictione, was related to Solon, architect of the Athenian constitution (594593). While Plato was still a boy, his father died and his mother married Pyrilampes, a friend of the great Athenian statesman Pericles. Plato was thus familiar with Athenian politics from childhood and was expected to enter it himself. Partly in reaction to the execution of his mentor and teacher Socrates in 399, he turned instead to philosophy, thinking that only it could bring true justice to human beings and put an end to civil war and political upheaval.

Few ancient authors have been as lucky as Plato. His works, which are predominantly dialogues, all seem to have survived. They are customarily divided into four chronological groups, though the precise ordering (especially within groups) is controversial:

Early: Apology, Charmides, Crito, Euthyphro, Hippias Minor, Hippias Major, Ion, Laches, Lysis, Menexenus

Transitional: Euthydemus, Gorgias, Meno, Protagoras

Middle: Cratylus, Phaedo, Symposium, Republic, Phaedrus, Parmenides, Theaetetus

Late: Timaeus, Critias, Sophist, Statesman, Philebus, Laws

This volume presents eight of the most widely read of these dialogues, drawn from every group except the last.

Plato also contributed to philosophy by founding the Academy, arguably the first university. It was a center of research and teaching both in theoretical subjects and also in more practical ones. Eudoxus, who gave a geometrical explanation of the presumed revolutions of the sun, moon, and planets around the earth, brought his own students with him to join Plato, and studied and taught in the Academy; Theaetetus developed solid geometry there. But cities also invited members of the Academy to help them in the practical task of developing new political constitutions.

The Academy lasted for some two-and-a-half centuries after Plato died, ending around 80 BCE. Its early leaders, including his own nephew Speusippus, who succeeded him as head, all modified his teachings in various ways. Later, influenced by the early dialogues, which end in puzzlement (aporia), the Academy, under Arcesilaus, Carneades, and other philosophers, practiced Skepticism; later still, influenced by different dialogues, Platonists were more dogmatic. Platonism of one sort or anotherMiddle or Neo- or something elseremained the dominant philosophy in the pagan world of late antiquity, influencing St. Augustine, among others. Much of what passed for Platos thought until the nineteenth century, when German scholars pioneered a return to Platos writings themselves, was a mixture of these different Platonisms.

Given the vast span and diversity of Platos writings and the fact that they are dialogues, not treatises, it is little wonder that they were read in many different ways even by Platos ancient followers. In this respect nothing has changed: different schools of philosophy and textual interpretation continue to find profoundly different messages and different methods in Plato. Doctrinal continuities, discontinuities, and outright contradictions of one sort or another are discovered, disputed, rediscovered, and disputed afresh. Neglected dialogues are taken up, old favorites reinterpreted. New questions are raised, old ones resurrected and reformulated: Is Platos Socrates really the great ironist of philosophy, or a largely non-ironic figure? Is Plato a systematic philosopher with answers to give, or an explorer of philosophical ideas only? Is he primarily a theorist about universals, a moralist, or a mystic with an otherworldly view about the nature of reality and the place of the human soul in it? Or is he all of these at once? Does the dramatic structure of the dialogues undermine their apparent philosophical arguments? Should Platos negative remarks about the efficacy of written philosophy (Phaedrus 274b278b) lead us to look behind his dialogues for what Platos student Aristotle refers to as the so-called unwritten doctrines (Physics 209b1415)?

Aside from this continued engagement with Platos writings, there is, of course, the not entirely separate engagement with the problems Plato brought to philosophy, the methods he invented to address them, and the solutions he suggested and explored. So many and various are these, however, that they constitute not just Platos philosophy, but much of philosophy proper. Part of his legacy, they are also what we inevitably bring to our reading of him.

SOCRATES

Socrates is the central figure in most of Platos works. In some dialogues this central figure is thought to beand probably isbased to some extent on the historical Socrates. As a result, these are often called Socratic dialogues. In the so-called transitional, middle, and late dialogues, however, the central figure is thought to be a mouthpiece for ideas that go well beyond Platos Socratic heritage.

In the Socratic dialogues, philosophy consists almost exclusively in philosophically pointed questioning of people about conventionally recognized moral virtues. What is piety? Socrates asks, or courage? or temperance? He seems to take for granted that there are correct answers to these questionsthat piety, courage, and temperance are each some definite characteristic or form (eidos, idea). He does not discuss the nature of these forms, however, or develop any explicit theory of them or our knowledge of them. He does not, for that matter, explain his interest in definitions, or justify his claim that if we do not know what, for example, justice is, we cannot know whether it is a virtue, whether it makes its possessor happy, or anything else of significance about it (Republic 354bc).

Despite this silence on Socrates part, there is nonetheless ample evidence that he sought definitions of forms because he thought of them as epistemic first principles, and that he did so because his model of genuine or expert knowledge was that of craft (techn). As a shoemaker, for instance, treats a well-made shoe as a pattern or paradigm in making another, so the moral expert, if he existed, would look to the form of piety (or courage or temperance, and so on) in order to decide what actions or people were pious and what it was that made them so (