This book made available by the Internet Archive.

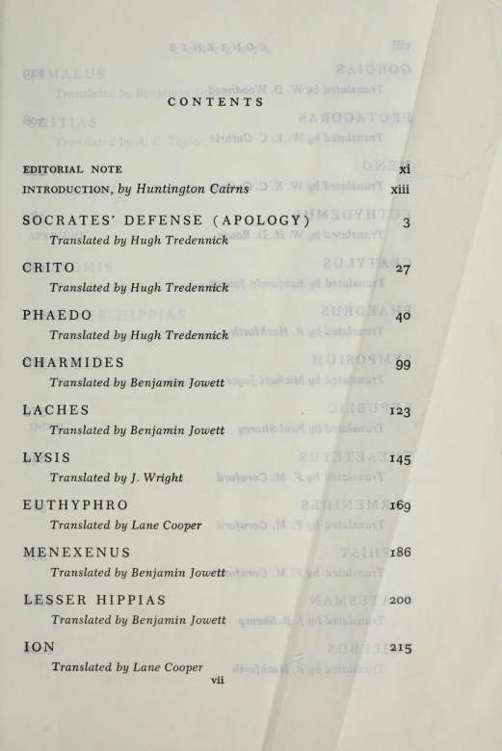

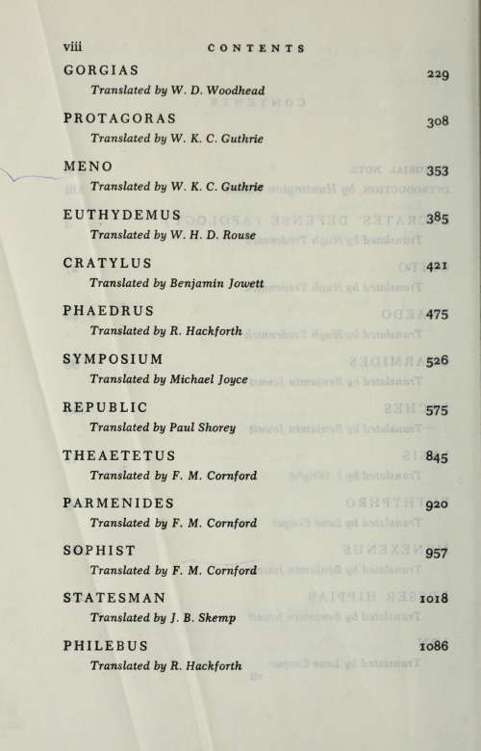

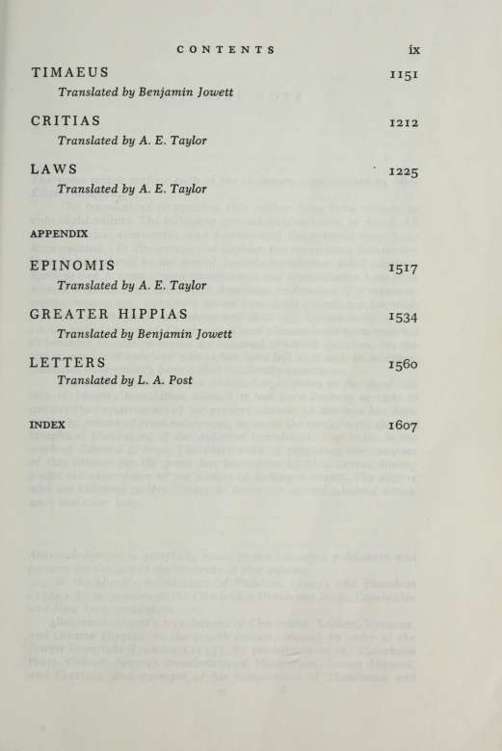

Translators

Lane Cooper F. M. Cornford W. K. C. Guthrie R. Hackforth Michael Joyce Benjamin Jowett

L. A. Post W. H. D. Rouse . Paul Shorey

J. B. Skemp A. E. Taylor Hugh Tredennick

W. D. Woodhead - J. Wright

EDITORIAL NOTE

The notes which preface each of the dialogues were written by Miss Edith Hamilton.

The translations comprising this edition have been subject to only slight editing. The following general revisions may be noted. All commentaries, summaries, and footnotes of the original texts have been omitted. (In Theaetetus and Sophist, the translator's summaries have been replaced by the text of Jowett's translation, third edition.) Spelling and, to some degree, punctuation and capitalization have been standardized, in accordance with American preferences. For measurements, money, etc., the Greek terms have been substituted for modern equivalents (such as furlong and shilling). Occasionally, where clarity would be served, Greek words and phrases have been inserted in brackets. Quotation marks are not used to set off speeches, but the use or nonuse of speakers' names has been left as it was. In addition, footnotes have usually been added to identify quotations.

The index is based on the Abbott-Knight index to the third edition of Jowett's translation, though it has been entirely remade to answer the requirements of the present edition. An attempt has been made, by means of cross-references, to assist the reader with the philosophical vocabulary of the different translators. The index is the work of Edward J. Foye. The chief work of preparing the contents of this volume for the press has been done by Mrs. Donna Bishop under the supervision of the editors of Bollingen Series. The editors also are indebted to Mrs. Mabel A. Barry for special editorial assistance and other help.

Acknowledgment is gratefully made to the following publishers and persons for the use of the contents of this volume:

R. Hackforth's translations of Philebus (1945) and Phaedrus (1952), by permission of the Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York, publishers.

Benjamin Jowett's translations of Charmides, Laches, Timaeus, and Greater Hippias, in the fourth edition, revised by order of the Jowett Copyright Trustees (1953), by permission of the Clarendon Press, Oxford. Jowett's translations of Menexenus, Lesser Hippias, and Cratylus, and excerpts of his translations of Theaetetus and

Xll EDITORIALNOTE

Sophist are from the third edition (1892), also published by the Clarendon Press.

Lane Cooper's translations of Ion and Euthyphro (copyright respectively 1938 and 1941 by him), by permission of Professor Cooper and of the Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, publishers.

A. E. Taylor's translation of Laws (1934), J. Wright's translation of Lysis (1910), and Michael Joyce's translation of Symposium (1935), by permission of J. M. Dent and Sons, London, and E. P. Dutton and Co., New York, publishers of these works in Everyman's Library.

Paul Shorey's translation of Republic (1930), by permission of the Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., publishers, and the Trustees of the Loeb Classical Library.

A. E. Taylor's translation of Critias (1929), by permission of Methuen and Co., London, publishers.

W. D. Woodhead's translation of Gorgias (1953) and A. E. Taylor's translation of Epinomis, edited by Raymond Klibansky (1956), by permission of Thomas Nelson and Sons, Edinburgh and New York, publishers.

Hugh Tredennick's translations of Apology, Crito, and Phaedo (1954) and W. K. C. Guthrie's translations of Protagoras and Meno (1956), by arrangement with Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, England, publishers.

L. A. Post's translation of the Epistles (1925), by permission of Professor Post.

W. H. D. Rouse's translation of Euthydemus, here first published, by permission of Mr. Philip G. Rouse and Mr. J. C. G. Rouse. Acknowledgment is gratefully made to the New American Library of World Literature, New York, for assistance in this connection.

F. M. Comford's translations of Theaetetus and Sophist (1935) and Parmenides (1939), by permission of Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, publishers.

J. B. Skemp's translation of Statesman (1952), by permission of Professor Skemp, the Yale University Press, New Haven, and Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, publishers.

INTRODUCTION

these dialogues were written twenty-three hundred years ago, and the thought of the ancient world, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and that of contemporary times, have all come under their influence. They have been praised as the substance of Western thought, as the corrective for the excesses to which the human mind is subject, and as setting forth the chief lines of the Western view of the world as they have never been delineated before or since in philosophy, politics, logic, and psychology. It has been held that a return to the insights of the dialogues is a return to our roots. But the dialogues have also had their enemies. They have been attacked as politically aristocratic and as philosophically mystical. However, few serious and fair students of the dialogues have ever denied their suggestiveness and the extent to which they stimulate thought. Many strands are interwoven in the dialogues but always at the center as their meaning is the Greek insight that Reason, the logos, is nature steering all things from within. In this approach nature is neither supernatural nor material; it is an organic whole, and man is not outside nature but within it. By concentration on this point of view and its implications Greek thought and art achieved a clarity never equaled elsewhere and Plato became its supreme spokesman.

Plato has been presented to us as a man of the study, a weaver of idealistic dreams; he has also been held up as a man with great experience of the world. There is no denying that he was learned, fully aware of the intellectual currents of his day. The variety of the quotations and allusions which appear in the dialogues show that he had read the extant literature. His life covered the period from the Peloponnesian War and the death of Pericles to Philip's capture of Olynthus. He was born about 428 B.C. and died at the age of eighty or eighty-one about 348 B.C. His family was an ancient one with political connections in high places and it is reasonable to assume that he saw military service in his youth. He had a wide acquaintance with the prominent men of his time, traveled extensively abroad, and at the age of forty founded the Academy and directed its affairs until his death. Thereafter the Academy had a continuous life of nine hundred years, a longer life span than that of any other educational institution in the West. This is scarcely the portrait of an armchair philosopher spinning theories in a study lined with books from floor to ceiling. It still leaves open, however, the question of the extent of

Next page