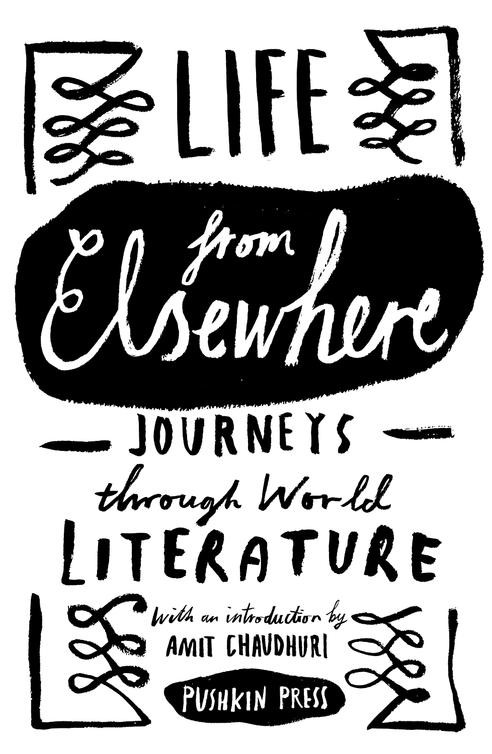

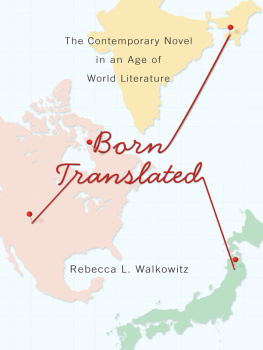

LIFE FROM

ELSEWHERE

JOURNES THROUGH

WORLD LITERATURE

CONTENTS

- Title Page

- Introduction

AMIT CHAUDHURII

AMIT CHAUDHURII - The Dream Called Africa

ALAIN MABANCKOU

ALAIN MABANCKOU - A Compass with Two Souths

ANDRS NEUMAN

ANDRS NEUMAN - To Understand a Culture Is Difficult, but

CHAN KOONCHUN

CHAN KOONCHUN - Lily

AYELET GUNDAR-GOSHEN

AYELET GUNDAR-GOSHEN - Divisions or Unity? Art and the Reality behind the Stereotype

SAMAR YAZBEK

SAMAR YAZBEK - When Ideas Fall in Line

ASMAA AL-GHUL

ASMAA AL-GHUL - Literature: Forbidden, Defied

MAHMOUD DOWLATABADI

MAHMOUD DOWLATABADI - Love and Oblivion

HANNA KRALL

HANNA KRALL - Sea of Voices

ANDREY KURKOV

ANDREY KURKOV - A Rallying Cry for Cosmopolitan Europe

ELIF SHAFAK

ELIF SHAFAK - WRITERS BIOGRAPHIES

- TRANSLATORS BIOGRAPHIES

- About the Publisher

- Copyright

INTRODUCTION

AMIT CHAUDHURI

MY PARENTS spoke with each other in Sylheti. They were both born in Sylhet, which had gone to East Pakistan upon partition, and theyd known each other since they were children. What they spoke was, admittedly, a gentrified version of this robust East Bengali dialect, often characterized (even by East Bengalis) as being, along with the dialect of Chittagong, near incomprehensible and slightly buffoonish. (Its worth recalling that the generic term for the East Bengali, bangal, also used to be synonymous with villager or yokel.) Sylheti is a variation of the standard Bengali that emanates from Calcutta, and, to many, its a comic variation. Besides, it is a language, as Marshall McLuhan would have put it, without an army and a navy, though standard Bengali doesnt have an army and a navy either. What standard Bengali did have, for a number of historical reasons, was cultural prestige. A great-uncle on my fathers side reportedly advised my parents against speaking in Sylheti with me (my father, by now, was working in Bombay), probably because of its low pedigree in the social world of languages: it was a language without a future, he told them. Given the considerable entrepreneurial skills of Bangladeshi Sylheti Muslims, who single-handedly invented Indian cuisine and curry in Britain, he was to be proved wrong, but I dont think hed have cared anyway. My future was going to be forward-looking and cultured; Sylheti couldnt possibly play a part in it.

Nevertheless, I continue to hear that tongue being spoken, and I once absorbed stories about Sylhetfrom my mother, mainly, but also my father and my maternal uncles. The comedic strain of much of this recounting was undeniable: it would have to do, for instance, with the hubris of cousins and cousins imbecilic best friends who, while generally unable to conduct a conversation in uninflected Bengali, had ambitionstransformed as they were by Tagore and modern Bengali literatureto become poets. So much in Sylhet was, it seemed, the bangals daydream. And then there was the political history: partition, and the loss of home, memories that went back to partially noticed tensions and misunderstandings with Muslim friends who would turn against the narrator of the tale at the time of the referendum that decided Sylhets future in 1947. One thing was clear: everything had happened in Sylhet. The upheavals of history had happened there; so had the newly minted magic of literature and the incursion of the songs of Tagore, Rajanikanta, D.L. Roy and Atul Prasad. Sylhet was the centre of the universe, if these reminiscences were to be trusted. It had the oiliest hilsa fish my mother had ever tasted; the most extravagant paat shaak greens. The pithha my mothers mother made were the most refined and delicate anywhere; this was borne out later by their reproduction in Bombay.

These memories could have added up to an account of a lost home, or a lost paradise or idyll, but they didnt. They could have been viewed through the lens of partition and exile, as the story of a continuing separation, but they werent. Sylhet, being neither Calcutta nor Dhaka, could have been interpreted as a peripheral location, but it wasnt. In my relatives narratives, it was, very simply, a centre. In other words, its appeal was neither personal nor immemorial; it was cultural and historical, animated by that moment to which those childhoods and that youth belonged. My relatives had been changed as well as made the people they were as a result of being situated in that town and in that history. For this reason, the division of the world into metropolitan centres and margins never quite rang true with me. Hardly anyone I met when I was growing up seemed to have actually known what it meant to live on the margins. They all seemed to have been located in the midst of history, wherever they came from.

What does it mean to be a centre? It doesnt entail transcending the local or even the provincial, as the example of Sylhet shows. Its self-sufficiency doesnt denote an independence from the outside world: where my parents and uncles were concerned, what we call the international was constantly impinging on their way of looking at things. But the international was most palpable in certain neighbourhoods and houses and conversations in Sylhet. To be in a centre meant believing you were in a centre; it meant to experience history as something you were being transformed by and might even contribute to. Much of this experience would happen in the head: in thoughts, speculations, longueurs, and in a form of immersion. This did not mean that this experience was less true than that of the centre, the city, in which the marks of metropolitan centrality were more overt. Nor did it mean that in the more canonical centres the experience of centrality was exclusively outward and visible, and unconnected to the daydream. All centres are to an important degree fictional and fictionalizing, in that they exist to some extent in the heads of people, in wishful thinking, and, as a result, are partly invisible. As the novelist and scientist Sunetra Gupta says about growing up in the Calcutta of the 1970s: It is not a criticism that our love for the city was rooted neither in its history nor in its geography, for where it existed was in the life of the mind of its inhabitants. The greatest excitements of living in a centre are internal, invented and not easily accessible from the outside.

Just as the life of the centre is often covert, and connected to the daydream, the marks of whatever it is that makes a culture, place or person international are implicit. In Japan, in the twentieth century, we could assume that the suitdark jacket and trousers and tie was a mark of (for the want of a better descriptive term) Westernization. But for the Bengali bourgeois, the suit was a sign of mimicry, as were the use of English and of cutlery. The minority that took on these habits was mockingly referred to as

Next page

AMIT CHAUDHURII

AMIT CHAUDHURII