PENGUIN

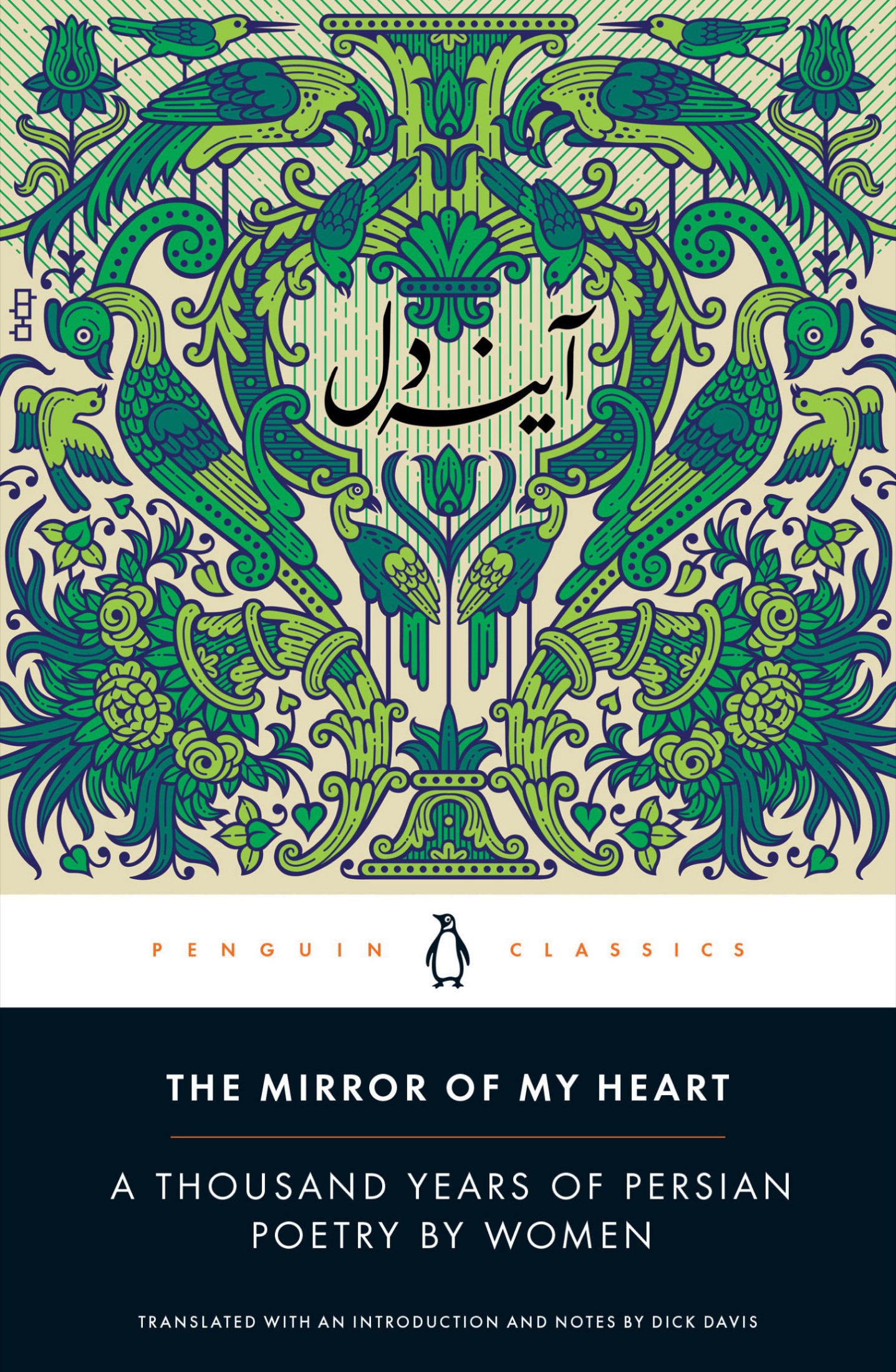

CLASSICS THE MIRROR OF MY HEART dick davis is the foremost English-speaking scholar of medieval Persian poetry in the West and our finest translator of Persian poetry (

The Times Literary Supplement). A fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and an emeritus professor of Persian at Ohio State University, he has published more than twenty books, including

Love in Another Language: Collected Poems and Selected Translations. His other translations from Persian include

The Conference of the Birds;

Vis and Ramin;

Layli and Majnun;

Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz; and

Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, one of

The Washington Posts ten best books of 2006. Davis lives in Columbus, Ohio.

PENGUIN BOOKS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com First published in the United States of America by Mage Publishers 2019 Published in Penguin Books 2021 Copyright 2019 by Mage Publishers Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture.

Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Names: Davis, Dick, 1945 translator. Title: The mirror of my heart : a thousand years of Persian poetry by women / translated with an introduction and notes by Dick Davis. Description: New York : Penguin Books, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020046588 (print) | LCCN 2020046589 (ebook) | ISBN 9780143135616 (paperback) | ISBN 9780525507260 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Persian poetryWomen authors. Classification: LCC PK6434.5.W64 M57 2021 (print) | LCC PK6434.5.W64 (ebook) | DDC 891/.55100899287dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020046588 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020046589 Cover design: Matt Vee Cover illustration: Homa Delvaray pid_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0 For Afkham, of course The liberating space that was Persian poetry... allowed subversiveindeed, hereticalexpressions forbidden in any other media. Skepticism, even about the most sacred beliefs and duties, and sneering at the authorities, religious and political, was tolerated as the fruit of poetic imagination. Abbas Amanat Womans crime in our country is to be a woman. Alam Taj (Zhaleh), Iranian poet (18831947) Contents THE MIRROR OF MY HEART The Poets THE MEDIEVAL PERIOD FROM 1500 TO THE 1800s FROM THE 1800s TO THE PRESENT Introduction A significant feature of Persian poetry that distinguishes it from most verse written in a European language is that almost all of itfrom the earliest poems, written over a thousand years ago, to the present dayremains relatively accessible to a contemporary speaker of the language.

The seventeenth-century English poet Edmund Waller bemoaned the fact that, already, his contemporaries could no longer easily read the works of the fourteenth-century poet Chaucer: But who can hope his lines should long Last in a daily changing tongue... We write in sand, our language grows, And like the tide our work oerflows. Chaucer his sense can only boast, The glory of his numbers lost! And as if to confirm Wallers complaint, it was in Wallers lifetime that passages from Chaucer were first translated into contemporary English, by Dryden. The Persian language, especially its literary form, has remained far more stable over the past millennium than is true of most European languages. There have been some changes of vocabulary and grammar, but by Western standards they are minor: a modern-day Iranian can read the works of the tenth-century poet Ferdowsi with about the same ease as a modern-day English speaker can read those of seventeenth-century authors such as Waller and Dryden; there are some difficulties for a non-specialist in the period, but they do not obscure what is usually the obvious sense and rhetorical force of any given passage. A side-effect of the fact that poems from centuries ago can seem and sound relatively contemporary to the Persian reader is that such poems could beand weretaken as models by poets from a much later date, and this in turn has led to a quite extraordinary continuity of poetic rhetoric from the earliest poems until at least the mid nineteenth century, and even beyond that period.

There is perhaps something else at work in this rhetorical continuity: all poetry is artificial in its language, but poetry in English has frequently tended to aim at language really used by men, as Wordsworth put it, Persian poetry tends to display, and delight in, its artifice. To say a poem in English sounds artificial is to condemn it; the same remark about a pre-modern Persian poem could well elicit the response Of course it does; its a poem, isnt it? And so the fact that a particular metaphor or rhetorical trope has been used by many other poets, and is thought of as intrinsically poetic rather than as colloquial, is not so much a barrier to its continued use as a validation of it. The poets Ayyuqi (tentheleventh centuries) and Nezami (twelfth century) both say that the poet is like the woman who tends to a brides physical appearance before her wedding; that is, the poet uses his or her skill and artifice to make the subject as dazzlingly beautiful as possible. Other common metaphors used by poets themselves to describe poetry are that it is something woven, such as brocade, or a piece of jewelry, such as a pearl necklace. All three of these metaphors emphasize the aesthetic, artificial, fabricated, and artisanal nature of the craft, rather than, say, its sincerity or its truth-telling qualities as they are foregrounded in much Western poetry (to hold... the mirror up to nature, as Shakespeares Hamlet says).

To indicate something of the density and complexity of this artifice in pre-modern Persian poetry, here is a translation of a very early poem that is made up almost entirely of motifs that belonged to a common stock widely utilized by other poets for centuries to come. The poem is by the tenth-century poet Rabeeh, who, as is appropriate for this volume, is the earliest-known woman poet to write in Persian: The garden shows so many flowers, as though Mani had painted their resplendent glow Dawns breezes never bore Tibetan musk, How is the world so musky when they blow? Are Majnuns eyes within the clouds, that they Shed Laylis cheeks hue on each rose below? Like wine within an agate glass, his tears Have filled each tulip with their crimson glow Raise up the wine bowl, raise it generously Since bad luck dogs deniers who say No Narcissi glow with silver and with gold Its Kasras crown their shining petals show Like nuns in purple cowls the violets bloom Do they turn into Christians as they grow? () The poem is a bahariehthat is, a poem welcoming the spring, a form that is still, a thousand years later, a recognized category of Persian poetryand it is set in the archetypal beautiful place for Persian culture, the locus amoenus to end them all, a garden. But what is Mani, the third-century founder of the religion of Manicheism, doing in the poem? In Persian lore he was also a painter whose beautiful paintings looked so true to life that they deceived both people and animals, and this accounts for painted in the second line. Because the flowers are compared to Manis paintings, this means they must be very beautiful, and Persian poetry takes it for granted that beauty is a major concern of every civilized person. And something else is also going on here: Mani was the founder of a pre-Islamic religion seen as a heresy by Moslems, and yet he is mentioned, apparently favorably, in a poem written by someone we presume to be a Moslem. Persian poetry often mentions religions other than Islam, and in short lyric poems, like this one, the reference is almost always either favorable or neutral; it virtually never implies condemnation (this is less true of long didactic poems, in which religions other than Islam are sometimes implicitly or explicitly condemned).

CLASSICS THE MIRROR OF MY HEART dick davis is the foremost English-speaking scholar of medieval Persian poetry in the West and our finest translator of Persian poetry (The Times Literary Supplement). A fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and an emeritus professor of Persian at Ohio State University, he has published more than twenty books, including Love in Another Language: Collected Poems and Selected Translations. His other translations from Persian include The Conference of the Birds; Vis and Ramin; Layli and Majnun; Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz; and Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, one of The Washington Posts ten best books of 2006. Davis lives in Columbus, Ohio.

CLASSICS THE MIRROR OF MY HEART dick davis is the foremost English-speaking scholar of medieval Persian poetry in the West and our finest translator of Persian poetry (The Times Literary Supplement). A fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and an emeritus professor of Persian at Ohio State University, he has published more than twenty books, including Love in Another Language: Collected Poems and Selected Translations. His other translations from Persian include The Conference of the Birds; Vis and Ramin; Layli and Majnun; Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz; and Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, one of The Washington Posts ten best books of 2006. Davis lives in Columbus, Ohio.