Contents

Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org

The publisher and the University of California Press Foundation gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Joan Palevsky Imprint in Classical Literature.

Music of a Thousand Years

Music of a Thousand Years

A New History of Persian Musical Traditions

Ann E. Lucas

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu .

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2019 by Ann E. Lucas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses .

Suggested citation: Lucas, A. E. Music of a Thousand Years A New History of Persian Musical Traditions . Oakland: University of California Press, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.78

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lucas, Ann E., 1978- author.

Title: Music of a thousand years : a new history of Persian musical traditions / Ann E. Lucas.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses . |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018051868 (print) | LCCN 2018054350 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520972032 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520300804 (pbk. : alk. Paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Music IranHistory and criticism. | Maqam. | Dastgah.

Classification: LCC ML344 (ebook) | LCC ML344 L83 2019 (print) | DDC 780.955 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018051868

For Sue

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

TABLES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe so much gratitude to so many people who both directly and indirectly facilitated my research and the production of this book. I must first thank Amir Hosein Pourjavady, Mohsen Mohammadi, Ali Jihad Racy, Anthony Seeger, and James L. Gelvin, all of whom directly educated me and guided the development of this book and made its publication possible. I am so grateful for all of the insight and critique you all provided over months and years. I also owe a great debit of thanks to Hamid Reza Maleki, who was so instrumental in facilitating my first trip to Iran. Thank you Hamid Reza for all of your help, and thank you to your wonderful family, who were all so welcoming to me during my time there. I would also like to thank Sassan Tabatabai, who read and critiqued many of my song text translations. I was hoping to avoid translating Persian poetry, as any translation of it feels highly unsatisfactory compared to the original. Thank you for helping me confront such challenges of poetry translation throughout the writing of my book.

There are many great music scholars in Iran and my ability to conduct research on the subject of Persian music relied directly on high-quality scholarship produced by Iranian scholars over the past several decades. Of these scholars I am greatly indebted to Hooman Asadi, Taqi Binesh, Hormoz Farhat, Sasan Fatemi, Mojtaba Khoshzamir, Ali Reza Mir Ali Naqi, Faramarz Payvor, Mansourah Sabetzadeh, and Sasan Sepanta. I am further indebted to the great legacy of ethnomusicological research in Iran, which includes scholars such as Stephen Blum, Margaret Caton, Jean During, Lloyd Clifton Miller, Owen Wright, and Ella Zonis. I would especially like to thank Bruno Nettl, whose own hypothesizing about the history of Iranian music and theoretical explorations of music history first got me interested how we narrate Iranian music history.

I truly stand on the shoulders of so many giants, whose work made my research possible in so many different ways. Please accept my heartfelt gratitude for all you have taught me over the years. I could not have researched this book without active assistance from other researchers, nor could I have done my work without the research of so many scholars that went before me.

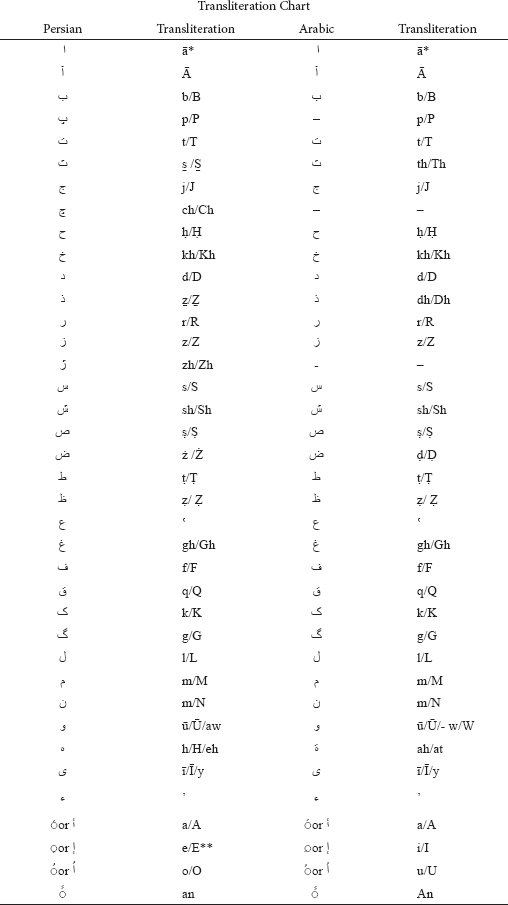

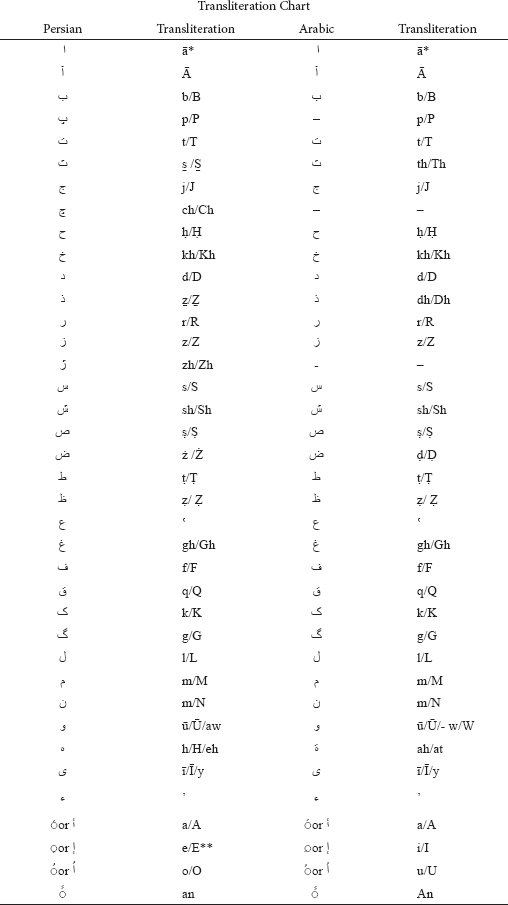

A NOTE ABOUT TRANSLITERATION

This book references indigenous terminology extensively. For the most part, indigenous terms that recur throughout the book are only fully transliterated once parenthetically when the term is first used. When referencing proper titles and terminology of specific texts, terms are transliterated for Persian if the original text was in Persian, and for Arabic if the original text was in Arabic. Foreign terms may be fully transliterated more than once for clarification of usage in specific contexts, or when cited directly from both Arabic and Persian language texts.

* diacritical omitted for initial

** also transliterated as -i for the Persian ezafeh grammatical particle

Ancient Music, Modern Myth

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

L . P . HARTLEY , THE GO - BETWEEN

The past is another planet.

NEIL DEGRASSE TYSON , COSMOS

In the fall of 2000, I was sitting in one of my classes at UCLA, eagerly awaiting an announced guest speaker. He was coming to teach us about traditional Persian music, one of Irans great music traditions. I was excited because I already had some knowledge of Arabic and Turkish music, but at the time I knew much less about Persian music. Arabic and Turkish music had many similarities as well as a shared history, so it seemed that Persian music would relate to these other cultures of the Middle East in some way. But the concept of Persian music clearly referenced something different in my imagination. It was an image of great antiquity. Great Persian empires stood in Central and West Asia long before the Arab expansion or Turkic migrations overtook these empires, so surely Persian music could be older than music from these other large regional cultures. In my mind, the idea of Persian music certainly carried a unique sense of history and cultural prestige in comparison with these other large language groups of the region.

The guest lecturer arrived and proceeded to give us a history of Persian music that met with my expectations. He first established that Persia and Iran were one in the same. When people spoke of Persian music, they were in fact talking about Iranian music associated with the Persian language. He then acknowledged that scholars knew very little about music of ancient Persia, but some vague evidence of Persian music-making was still observable in bas reliefs and other artifacts found among the ruins of the Achaemenid Empire (700330 BCE ) and the Sassanian Empire (224650 CE ). He began teaching about the known history of Persian music from the same era of history when narrations of Arabic music history often begin: after the rise of Islam, starting around the ninth century CE . My assumptions were correct: the history he told did indeed portray Iranians as active participants in a cosmopolitan music culture, first in the company of the Arabs and later in the company of Turkic and even Mongol peoples. There had basically been one general set of extensively documented musical principles that Iranians had shared with other language groups of the Middle East for many centuries, within a shared culture that paired Islam with a dynastic system of kingship. As the guest lecturer narrated this history, he highlighted key historical writings and sources on music in the Persian language, focusing on the very important role of Iranians in this extensive, sophisticated music culture.