Praise for POETS & PAHLEVANS

Di Cintios Iran yields the countrys most beguiling images: pomegranate groves, poets mausoleums, ripening dates, poetry over dinner and village wrestling tournaments.

The Globe and Mail

A charming retreat. Poets & Pahlevans is so graceful and sympathetic as to make anyone fall in love with [Iran]. The result is finely balanced, taking into account both the romance and wretchedness of modern Iran. Di Cintio has a poets eye for imagery and his descriptions are marvellous, whether of fallen sprays of scarlet blossoms, the play of light on mosaics or the twisting backstreets of venerable cities.

Calgary Herald

Like Michael Moore in the documentary Roger and Me, Di Cintio is on a quest and he doggedly follows up on every lead. From the well-known tourist destinations of Esfahan, Shiraz and Bam to the most obscure Kurdish village, the glimpses of the lives of ordinary Iranians are memorable.

Winnipeg Free Press

Praise for HARMATTAN

Marcello Di Cintio is a fine, fine talent to be savoured.

Wayson Choy

An honest writer, rendering not only the marvels of what he sees and feels, but the entire odyssey, his vulnerabilities, flaws and low points Di Cintios travelogue stands apart from anothers by inviting the reader into his thoughts.

Calgary Herald

This book isnt just a good travelogue, its a great story; you dont have to be a traveller to appreciate it.

See (Edmonton)

Like the Harmattan wind itself, Di Cintios story blows into the reader and swirls images around, leaving a dusty layer of grit to mull over.

Georgia Straight

For Moonira, with love

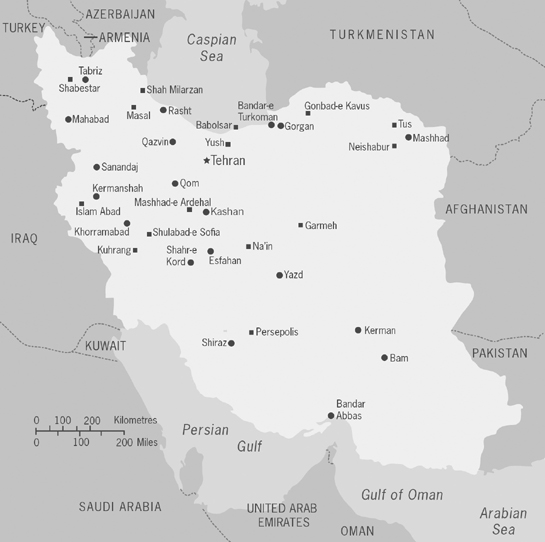

IRAN

What you most want,

what you travel around wishing to find,

lose yourself as lovers lose themselves,

and youll be that.

FARID AL-DIN ATTAR NEISHABURI

Know then that the art of wrestling is accepted and

praised by Kings and Sultans, and that of those who

practise it, most are pure and righteous.

WAEZ-E KASHEFI

1

INTO IRAN

And now they meetnow rise, and now descend,

And strong and fierce their sinewy arms extend;

Wrestling with all their strength they grasp and strain,

And blood and sweat flow copious on the plain;

Like raging elephants they furious close;

Commutual wounds are given and wrenching blows.

Sohrab now claps his hands, and forward springs

Impatiently, and round the Champion clings;

Seizes his girdle belt, with power to tear

The very earth asunder

A n old man recites poetry into a microphone. The measured verses float over the assembled crowd through a static-garbled loudspeaker. When the poem ends he calls two wrestlers to the centre of the circle. Both are barefoot, and both brush the ground with their fingertips before touching their lips and forehead. This is an invocation to Allah, something I dont quite understand. Village men sit on the perimeter in their white turbans and old fedoras, smoke cigarettes and spit out black sunflower seeds. They shout and cheer their muscled heroes.

The wrestlers shake hands and kiss each other on both cheeks, then lock their arms around each other in a warriors embrace. Their bodies, now merged, are tense and already sweating. I can see their faces: both are nervous but resolute. Their stillness is momentary. When a referee taps them on their shoulders the men clash.

The poetry, epic tales of ancient wars and legendary heroes, was meant to inspire the wrestlers in their battle, but now the crowds roar replaces the old verses in their scarred ears. They push each other back and forth in the circle, maintaining their grip around each others waist. Their knuckles blanch. The dust mingles with their sweat and slicks their legs with salty mud. The mob wave their arms and holler instructions in the village dialect. Young boys bounce on their grandfathers laps.

Then one wrestler thrusts his body forward. His grip turns to stone and he lifts his opponent from his feet. The noise of the crowd swells. The man hurls his rival to the ground and crashes down on top of him. They are invisible in the cloud of dust until the referee helps them stand. Both are filthy and exhausted, but only one man is a winner. The referee raises his arm and the two wrestlers shake hands and kiss again. The victor strides into the throng of his fans and is immersed in their cheers. The loser leaves alone.

When I pressed the button at the Iranian consulate in Istanbul I had no reason to be confident. I wasnt granted a visa from the embassy in Ottawa and the verdict on my visa in Istanbul had already been delayed twice. I did not know why. Admitting I was a writer was, in retrospect, a strategic error; Iran is famously wary of foreign journalists. Also, Toronto was in the middle of its SARS crisis. Canadians were being turned away at borders around the world. The man at the embassy who accepted my visa application wasnt overly diligent on this point. Do you have SARS? he asked. I said no and that was that. I worried, though, that his superiors might be less cavalier.

I waited for nearly two weeks, wandering through the fabulous mosques that crown each of Istanbuls hills and point the way to heaven with their slender minarets. Five times a day the call to prayer boomed out over the city and gave a moments respite from the Turkish pop music blaring from every storefront and taxicab. Fashionable Istanbulus smoked water pipes and drank tea in popular garden cafs. The bazaars were filled with briny olives, Turkish silks, Ottoman antiques and cheesy belly-dance costumes. It had been three years since my last visit to the Middle East and it was a pleasure to be back among the pistachio vendors, tea houses and honey-soaked pastries.

But for all Istanbuls charms, my mind was a thousand kilometres east. Id spent the last two years infatuated with Iran. I had read Persian history and become obsessed with Irans politics, but it was the Persian love for poetry that first drew me to the place. I learned that all Iranians, even small children, could recite poetry from memory. Poets who have been dead for centuries are revered. Their verses resonate over time and colour everyday language. I wanted to investigate this devotion and be in a place where bazaaris and taxi drivers spoke in measured verse. Istanbul was a poor consolation. I wanted to be in Iran.

While the consulate deliberated on my visa application, I bought my ticket for the Trans-Asya Express to Tehran, and did all the things I knew I would not be able to do once I crossed the border. I watched American action films in modern cinemas. I went to European-styled coffee shops to sip espresso, and drank pints of Efes lager in noisy bars. I read a copy of Salman Rushdies

IRAN

IRAN