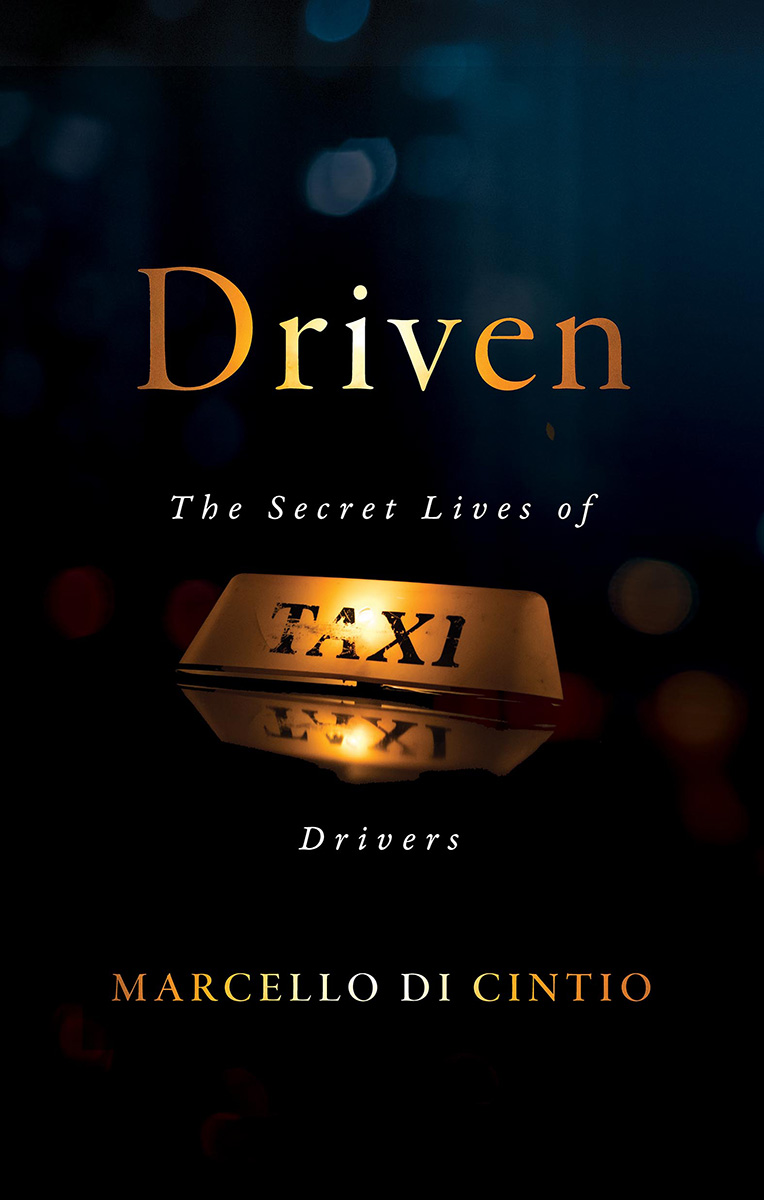

On a few occasions, I have changed the names of cabbies family members due to privacy concerns. The identities of all drivers, however, remain unobscured.

Introduction

Between Story and Silence

I hate taking taxis.

My near quarter century as a travel writer has landed me in the backseats of countless taxicabs around the world, and their drivers have been my most common nemeses. Nearly every ride I have taken in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia, where taxi meters are either nonexistent or conveniently broken, has sparked a squabble over the fare. For me, taxis represent a necessary evil at best, and a cause for angry conflict at worst. Once, at the end of a ride in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, I recklessly called the driver a thief and he lunged out of the car at me, ready for a fight. An Iranian driver almost punched me, too, when I petulantly slammed his door after I thought he overcharged me. Luckily, both men calmed down before throwing their fists. My stature hardly matches my temper, and I wouldve lost those fights.

My most potentially dangerous taxi ride, though, occurred in eastern Turkey during my honeymoon. I sat up front and my new bride sat in the back, next to a strange man who appeared to be a friend of the driver. As soon as we left the border, our cabbie pulled a tall can of Efes Lager from beneath the drivers seat and drained it in one long pull. Then he drank a second. The driver also kept a knife with a five-inch blade on the armrest between his seat and mine. I was convinced that he and his backseat buddy planned to rob us at knifepoint, or worse, if he didnt first drunk-drive us off the road into the Black Sea. I picked up his knife and held it my hand for the duration of the ride, pretending to admire it, just to ensure he remained unarmed. Thanks to these kinds of experiences, I now possess a lingering dread of taxis in generala Post-Taxi Stress Disorder.

Cabbies engender more sympathy from me than suspicion in places where the meters work and I dont fear being cheated or stabbed. As an enthusiastic traveller, I can hardly imagine anything worse than being in constant motion but never really going anywhere. Still, at home, Id rather use public transit and car-share services than hail a cab, and I always accept offers of rides from family and friends. I adore cities like New York and Montreal as much for their extensive subway systems as their restaurants and cafs. And I walk a lot. I miraculously dropped ten pounds during a month-long trip to Belfast, where I mainly subsisted on draft beer and things made from potatoes, as a side effect of walking everywhere.

When I do end up taking a taxi, I tend to slip into the backseat and blurt out a destination. If Im feeling beery and chatty, I might try to geolocate my cabbies name or accent in case he comes from somewhere Ive been. This is less an attempt at camaraderie than a clumsy excuse to boast about my travels. Is your accent Persian? Ive been to Iran twice, I might say. Or Youre from Nigeria? I spent a year in West Africa. Never made it to Nigeria, though. I am not proud of these inane exchanges. Theyre a more pompous version of where are you from?the question Ive learned taxi drivers hate the most.

More often, though, I dont speak at all, opting instead to mutely stare at my phone. I know I am not alone in this; a cabbie once told me his silent fares sometimes make him feel like hes simply another part of the car. As passengers, we rarely wonder at the lives of those we know only by the reflection of their eyes in a rear-view mirror. We dont inquire about the lives of our baristas or butchers or bank clerks, either, but the physical closeness between cabbie and passenger makes such silent disinterest feel unnatural. Antisocial, even.

I suspect this has always been the case. I doubt Thornton Blackburn, who became Upper Canadas first taxi driver in 1837, engaged much with his clients either. The configuration of Blackburns cab did not lend itself to conversation. Passengers sat inside the red-and-yellow horse-drawn carriage while Thornton worked the reins up top. Had they spoken to Thornton at all, his clients might have glanced at his Black face, heard his unfamiliar accent, and asked him where he came from. Kentucky, hed have said. Thortons clients, their brief pleasantries exhausted, might have returned to the pages of the weeks Upper Canada Gazette in the same way todays passengers dissolve into the quiet glow of their Twitter feeds.

But Thorntons life history hints at what we might be missing. Ones birthplace alone does not tell a story. Thornton and his wife, Lucie, didnt just come from Kentucky. They came from slavery. The Blackburns escaped their slave masters in high summer of 1831. They used forged documents to book passage across the Ohio River on a steamboat named the Versailles. Thornton and Lucie continued on to Detroit, where they lived for two years before getting arrested as runaway slaves. Then they escaped again. Lucie walked out of her prison cell after swapping clothes with a friend who agreed to take her place. Thornton was freed by a throng of Detroits Black citizens, who armed themselves with pistols, knives, and clubs and overwhelmed the prison guards. The Blackburns reunited in Canada, but were jailed again while their American owners sued for their extradition. Since Thornton and Lucie had committed no crime in Canada, however, the court would not send them back. The Blackburns exoneration established Canada as a safe haven for fugitive slaves from America.

Surely, none of Thorntons taxi clients could have imagined that their driver and his fearless wife had laid tracks for the Underground Railroad. They could not have known that many of the 35,000 escaped American slaves who found safe haven in Canada owed their freedom to the man sitting on their taxis roof. They had no idea about the story they werent hearing.

After reading about the Thorntons, I started to wonder what stories I was missing. Id spent years crossing borders around the world to document suffering and injustice. Resilience and love. Yet I hardly needed to leave Canada for these stories. I couldve found almost as many on my cab rides to and from the airport, because the taxi itself is a border. Beneath the roof light of every cab, a map of frontiers and dividing lines unfolds. The taxi occupies the margin between public and private space: accessible to all but simultaneously personal and intimate. The taxi is the border between autonomy and servitude. The cabbie has no superior to answer to; instead, each fare brings a new master to whom he briefly yields. Even a poor man is a boss in a taxi. The taxi can be the border between the wealthy and working class, and between white people and people of colour. Nowhere else do people so different share such close quarters and engage so little. If the USMexico border is, as writer Gloria Anzalda once described, the place where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds, a taxi is the place where the First World rubs against the Third and stares at its phone.

For me, the most compelling taxicab borderline is drawn here, between silence and the stories that silence conceals. And so, in 2018, I decided to cross that border. I put away my passport and spent a year travelling around Canada to seek out the life stories of the nations taxi drivers. I would speak with cabbies outside their cars, for fear the enclosed space and running meter would transform our discourse into a costly interrogation rather than a real conversation. I wanted to meet drivers somewhere they would feel comfortable, too. This meant spending a disproportionate amount of time amid the familiar brown tiles of Tim Hortons.