Marcello Di Cintio - Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense

Here you can read online Marcello Di Cintio - Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Saqi, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

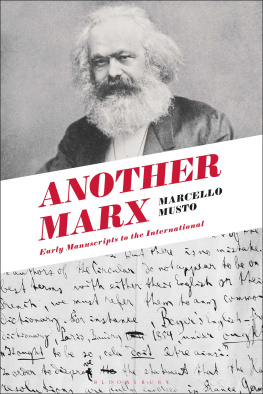

- Book:Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense

- Author:

- Publisher:Saqi

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Marcello Di Cintio is the author of four books, including the critically acclaimed Walls: Travels Along the Barricades, winner of the 2013 Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing and the City of Calgary WO Mitchell Book Prize. Di Cintios work has also been published in Geographical, Canadian Geographic, the International New York Times, Cond Nast Traveller and Afar. He lives in Calgary, Canada.

www.marcellodicintio.com

BY MARCELLO DI CINTIO

Walls: Travels Along the Barricades

Song of the Caged Bird

Poets and Pahlevans: A Journey into the Heart of Iran

Harmattan: Wind Across West Africa

Marcello Di Cintio

to the Rockets

Palestine in the Present Tense

SAQI

Saqi Books

26 Westbourne Grove

London W2 5RH

www.saqibooks.com

Published 2018 by Saqi Books

Copyright Marcello Di Cintio, 2018

Marcello Di Cintio has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

By arrangement with Westwood Creative Artists Canada

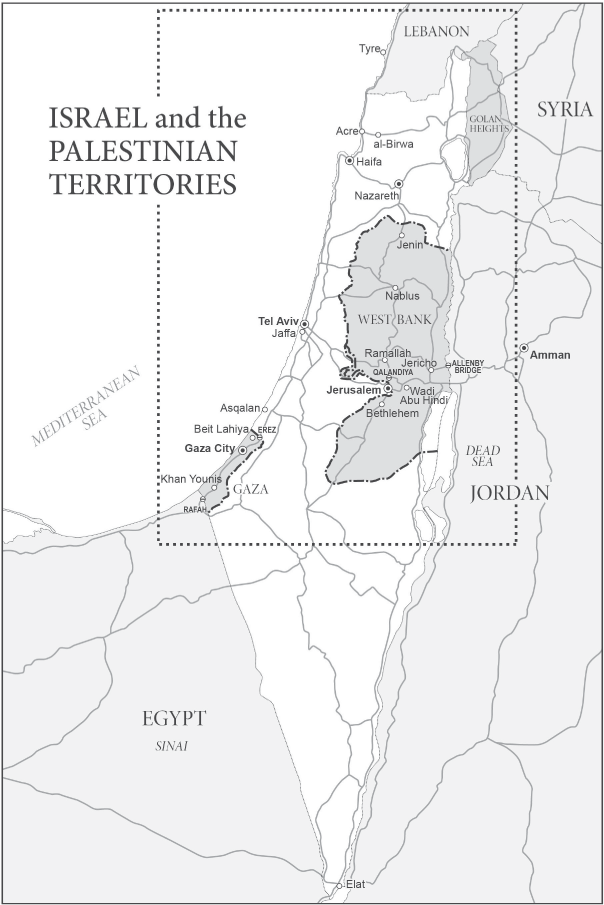

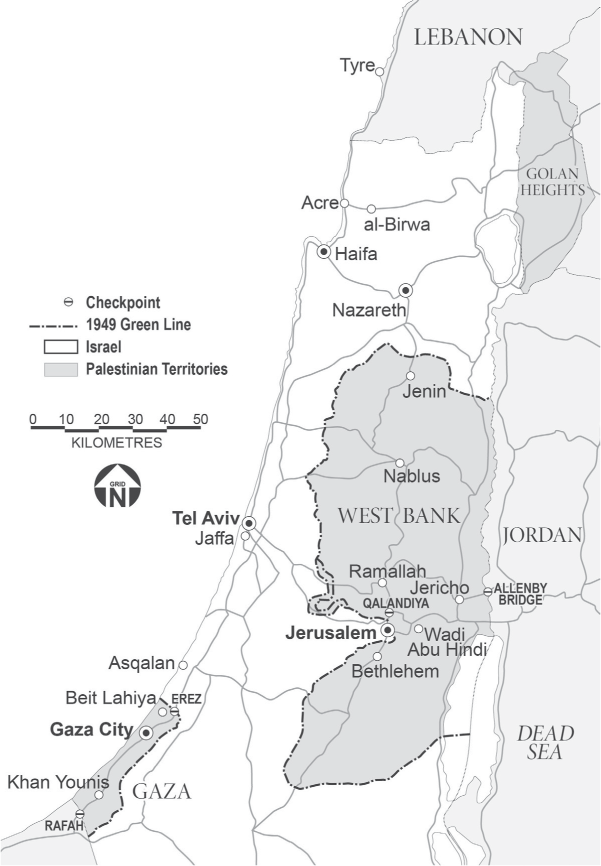

Map by Jim Todd, Todd Graphic,

Reprinted by permission of Goose Lane Editions

from the Canadian edition of Pay No Heed to the Rockets

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Every reasonable effort has been made to obtain the permissions for copyright material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, however, the publishers will correct this in future editions.

ISBN 978 0 86356 980 7

eISBN 978 0 86356 985 2

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Chatham, ME5 8TD

In 1996, Mourid Barghouti sat in a waiting room on the Jordanian side of the Allenby Bridge. He passed the time leafing through the manuscript pages of what would become his ninth book of poetry. But anxiety about the quality of his poems a typical writers doubt compelled him to return the manuscript to his bag. Instead, he reflected on the first poem he ever published, Apology to a Faraway Soldier, which came out on the first day of the 1967 Six-Day War. The Arab armies fell to the Israelis by the sixth day, and the river Barghouti now waited to cross became a border. Barghouti once joked, I wonder if the Arabs were defeated and Palestine was lost because I wrote a poem.

In his memoir I Saw Ramallah, Barghouti describes stepping out of the waiting room and glancing west across the bridge at the land of Palestine after three decades of exile:

Who would dare make it into an abstraction now that it has declared its physical self to the senses?

It is no longer the beloved in the poetry of resistance, or an item on a political party program, it is not an argument or a metaphor. It stretches before me, as touchable as a scorpion, a bird, a well; visible as a field of chalk, as the prints of shoes.

I asked myself, what is so special about it except that we have lost it?

Eventually, a Jordanian soldier told Barghouti he could cross the bridge. He walked with a small bag on his left shoulder and the bridges prohibited wooden planks creaking beneath his feet. Behind me the world, he wrote, ahead of me my world.

Nineteen years later, I sat in the same waiting room as Barghouti, or one just like it, and waited for my chance to follow his footsteps across the border. After Id waited in the Jordanian departure salon for an hour with a group of Palestinian families, a border soldier returned our passports and led us outside. The wooden bridge Barghouti walked across was no longer in use. This disappointed me. I wanted to retrace his footfalls on Allenbys prohibited wooden planks. The new paved crossing robbed the journey of its pedestrian poetry. Instead, we boarded a bus already nearly full of travellers from other waiting rooms. We drove for a few metres before stopping behind a line of identical buses stretching from the Jordanian border to the customs post on the other side. When our driver realised the buses were not moving, he pulled ours out of the line and roared past the unmoving vehicles to the front where he talked his way past the official at the checkpoint. Then he edged the bus into a space in front of the Israeli border post. Some of the passengers applauded. Half of them passed Jordanian banknotes to the driver as a tip.

We waited inside the bus for another quarter of an hour before being allowed to exit into the chaos of the checkpoint. Hundreds of people, mostly Palestinian families, fought to navigate the gauntlet of Israeli security. Many of the Palestinians were returning from Umrah pilgrimages to Mecca and carried large plastic vessels of water with them, a sacred liquid souvenir from the holy Zamzam well in the Great Mosque.

Each arrival pressed through the mob under the disinterested gaze of young Israel Defense Forces soldiers. The border soldiers always looked bored to me, whether here on the bridge, on the smooth tiles of Ben Gurion airport, or at the West Bank checkpoints. Barghouti noticed this, too. When he passed through here, he looked at the face of one of these soldiers. For a moment he seemed a mere employee, Barghouti wrote. At least his gun is very shiny. His gun is my personal history. It is the history of my estrangement. His gun took from us the land of the poem and left us with the poem of the land.

I merged into the current of bodies and pushed my way to a counter where I showed my passport to an Israeli soldier in exchange for tags for my backpack. Then I squeezed out of the queue and toward a conveyor belt that swept my bag somewhere inside the building. Finally, I joined three successive lines in front of three different glass booths to show my documents to three different officials. The last, a woman of about twenty years, asked me where I planned on staying and what I planned on doing. She interrupted me when I started to list the Palestinian writers I wanted to meet. Dont say Palestine, she said. This is Israel. Stop saying Palestine.

In the summer of 2014, Israel launched Operation Protective Edge against militants in the Gaza Strip. During a brief lull in the bombing, a series of four photos emerged of a young Gazan girl sifting through the wreckage of a destroyed building. The girl, around ten years old, wore a green dress and pink leggings, her long hair tied back in a neat ponytail. In the photos, she pulls books from beneath shattered concrete and cinderblocks and stacks them in her arms. The books are tattered and filthy, their covers dangling from their bindings. But in the last photograph, the girl walks away, smiling.

Few images from Gaza had as profound an effect on me as these four photos of this girl. Id seen countless photos from the war. Most portrayed Palestine as a place of pain and ugliness. But the girl in Gaza was beautiful in the way all children are beautiful, and more beautiful still for the unexpected flash of her green dress against the grey rubble. Her broken books reminded me, too, that nothing possesses more beauty or more humanity than a story. To weave the snarled strands of a life, either real or imagined, into literature is a form of blessed alchemy. Twists of plot and turns of phrase mirror the messy details of human existence. We are nothing more or less than the stories we tell. But the only story most outsiders ever hear about Palestine is a thin volume of enduring conflict. The character of the Palestinian is either a furious militant throwing stones with a keffiyeh wrapped around his face, or an old woman in hijab wailing in front of her destroyed home. This single narrative of anger and deprivation holds the Palestinians hostage, and little artistry is to be found in such a plot.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense»

Look at similar books to Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.