Contents

Matt Malone, SJ

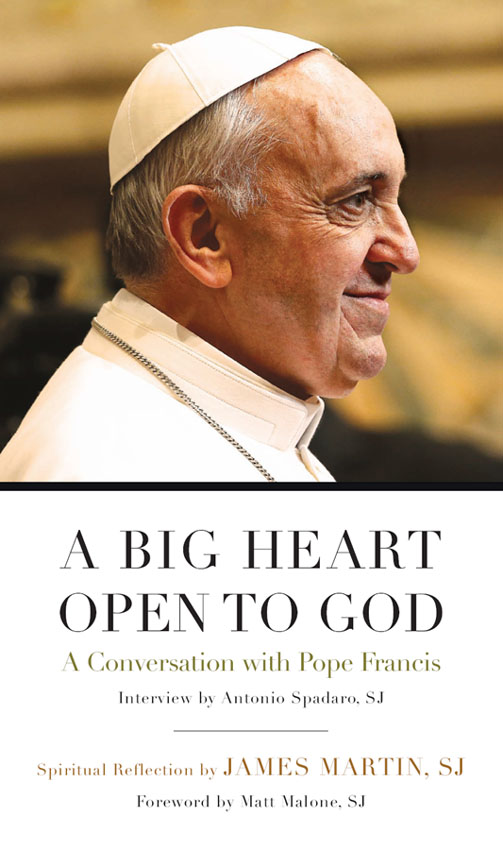

ORGANIZATIONS AS OLD as America rarely do anything completely unprecedented. For every new idea, there is a pretty good chance it has been done before, in one way or another, during the course of 104 years of weekly publishing. This interview in America, however, is truly a first.

Although we have always been committed, on a wide and varied field of subjects, as one of my predecessors put it, to the principles enunciated by the popes, the Vicars of Christ, and found in the major statements of the American hierarchy, America has never before been primarily responsible for conveying the words of a pope to an American audience. The fact that the current pope is a Jesuit is not irrelevant, of course, and neither is the fact that this interview is being simultaneously published by our fellow Jesuit journals in the worlds other major languages.

The situation is so unusual, however, that it might be helpful to know how it came about. As with a lot of things, it began with an innocent, offhand remark. James Martin, SJ, America s editor at large, and I were catching up in my office a few weeks after the election of Pope Francis. We were talking generally about our editorial approach to the new papacy when Father Martin said, Why dont we try to interview the pope? I gave it three seconds of thought and said, Yes, why not?

An interview seemed unlikely and would be unprecedented, but we had just lived through six weeks of unlikely and unprecedented events. We briefly discussed how to approach the matter and started to ask around, conferring with Jesuit colleagues in Washington, D.C., and Rome. They all suggested that we contact Federico Lombardi, SJ, the popes spokesperson. Father Lombardi responded with his customary alacrity and aplomb and told us that in general the pope does not like to do interviews, but that perhaps he could ask the pope our questions during a press conference and that could be a kind of interview.

Around this time, we learned that our colleagues at La Civilt Cattolica, the Jesuit journal edited in Rome, were now also interested in conducting an interview. We concluded that their proximity to the pope, as well as the fact that all content in Civilt must be preapproved by the Vatican, made them the ideal partner. Antonio Spadaro, SJ, of Civilt, then approached Father Lombardi on behalf of both of our journals, and Pope Francis consented to the interview.

At the annual meeting of the editors of major Jesuit journals in Lisbon in late spring, the decision was made to include the Jesuit journals from the other major language groups. We also settled on a format. The editors of each of the journals would submit questions to Father Spadaro, who would organize and collate them and then pose them to the pope in an in-person interview. Once Father Spadaro had transcribed the interview and edited it for clarity and length, he personally reviewed the text with the pope, who approved it for publication. America then commissioned a team to translate the text into English. And the rest, as they say, is history.

I leave it to you to judge the popes remarks in these pages, but I would like to suggest one way of reading the interview. Other popes have given interviews, of course, and while they have been insightful and often spirited, they have also been didactic and formal. I suspect that this interview, along with the popes extended remarks on the return trip from Rio de Janeiro last July, represent a new genre of papal communication, one that is fraternal rather than paternal. A spirit of generosity, humility, and, dare I say, deep affection is evident in these pages. To put it another way, there is no hint here of the monarchical, preconciliar papacy. Pope Francis speaks to us as our brother; his we actually means we, not I.

Matt Malone, SJ, is editor in chief of America .

The Exclusive Interview with Pope Francis

THIS INTERVIEW WITH Pope Francis took place over the course of three meetings during August 2013 in Rome. The interview was conducted in person by Antonio Spadaro, SJ, editor in chief of La Civilt Cattolica, the Italian Jesuit journal. Father Spadaro conducted the interview on behalf of La Civilt Cattolica, America, and several other major Jesuit journals around the world. The editorial teams at each of the journals prepared questions and sent them to Father Spadaro, who then organized and consolidated them. The interview was conducted in Italian. After the Italian text was officially approved, America commissioned a team of five independent experts to translate it into English: Massimo Faggioli, Sarah Christopher Faggioli, Dominic Robinson, SJ, Patrick J. Howell, SJ, and Griffin Oleynick. America is solely responsible for the accuracy of this translation.

IT IS MONDAY, August 19, 2013. I have an appointment with Pope Francis at 10 a.m. in Santa Marta. I, however, inherited from my father the habit of arriving early for everything. The people who welcome me tell me to make myself comfortable in one of the parlors. I do not have to wait for long, and after a few minutes I am brought over to the lift. This short wait gave me the opportunity to remember the meeting in Lisbon of the editors of a number of journals of the Society of Jesus, at which the proposal emerged to publish jointly an interview with the pope. I had a discussion with the other editors, during which we proposed some questions that would express everyones interests. I emerge from the lift, and I see the pope already waiting for me at the door. In meeting him here, I had the pleasant impression that I was not crossing any threshold.

I enter his room, and the pope invites me to sit in his easy chair. He himself sits on a chair that is higher and stiffer because of his back problems. The setting is simple, austere. The workspace occupied by the desk is small. I am impressed not only by the simplicity of the furniture, but also by the objects in the room. There are only a few. These include an icon of St. Francis, a statue of Our Lady of Lujn (patron saint of Argentina), a crucifix, and a statue of St. Joseph sleeping, very similar to the one which I had seen in his office at the Colegio Mximo de San Miguel, where he was rector and also provincial superior. The spirituality of Jorge Mario Bergoglio is not made of harmonized energies, as he would call them, but of human faces: Christ, St. Francis, St. Joseph, and Mary.

The pope welcomes me with that smile that has already traveled all around the world, that same smile that opens hearts. We begin speaking about many things, but above all about his trip to Brazil. The pope considers it a true grace.

I ask him if he has had time to rest. He tells me that yes, he is doing well, but above all that World Youth Day was for him a mystery. He says that he is not used to talking to so many people: I manage to look at individual persons, one at a time, to enter into personal contact with whomever I have in front of me. Im not used to the masses.

I tell him that it is true, that people notice it, and that it makes a big impression on everyone. You can tell that whenever he is among a crowd of people his eyes actually rest on individual persons. Then the television cameras project the images, and everyone can see them. This way he can feel free to remain in direct contact, at least with his eyes, with the individuals he has in front of him. To me, he seems happy about this: that he can be who he is, that he does not have to alter his ordinary way of communicating with others, even when he is in front of millions of people, as happened on the beach at Copacabana.

Before I switch on the voice recorder we also talk about other things. Commenting on one of my own publications, he tells me that the two contemporary French thinkers that he holds dear are Henri de Lubac, SJ, and Michel de Certeau, SJ. I also speak to him about more personal matters. He too speaks to me on a personal level, in particular about his election to the pontificate. He tells me that when he began to realize that he might be elected, on Wednesday, March 13, during lunch, he felt a deep and inexplicable peace and interior consolation come over him along with a great darkness, a deep obscurity about everything else. And those feelings accompanied him until his election later that day.