Surge of Piety

Surge of Piety

Surge of Piety

Norman Vincent Peale and the Remaking of American Religious Life

CHRISTOPHER LANE

Copyright 2016 by Christopher Lane.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Quotations from the following are reprinted with permission.

Analytical Study of a Cure at Lourdes by Smiley Blanton, copyright 1940 by The Psychoanalytic Quarterly. Used by permission of Wiley Global, an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Diary of My Analysis with Sigmund Freud by Smiley Blanton, copyright 1971 by Margaret Gray Blanton. Used by permission of Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Minion type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016937984

ISBN 978-0-300-20373-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Introduction

I n the winter of 1936, as political tensions pushed Europe once more to the brink of war, Norman Vincent Peale, the New York minister and soon-to-be best-selling author of The Power of Positive Thinking, gave one of his darkest political sermons. The issue of the hour, he warned his congregation and the attendant press, was a fierce cultural battle between Christ and Marx. Although rising militarism in Germany and Japan would lead both countries to declare war on the United States five winters later, to Peale neither was an immediate threat. In the stark opposition he conjured, the nation faced a graver danger and an increasingly urgent imperative: it must choose between Church and the Reds.

Peale was not alone in using fear of communism to stoke religious sentiment across the United States. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, as much of the world succumbed to totalitarianism, influential politicians and religious leaders in the United States pressed hard on the idea that in religion the nation would find both unity and redemption. Together, they cast the country as distinguished by its commitment to Freedom Under God, to Spiritual Mobilization, and to various crusades, all of them aligning religious nationalism with spiritual uplift and resilience. Peale, by then one of the nations most prominent and vocal ministers, played an outsize role in connecting that message to positive psychology and religio-psychiatry and to broadcasting their claims. Urging Americans to find a religious solution to their problems, he gave belief in oneself and country religious significance. To be a normal and healthy American, he asserted, was to be a devout one.

Peales ultimatumchoose between Church and the Redspersuaded Americans in large numbers to take refuge from communism in evangelical Christianity, including its religiously themed perspective on physical and mental health. How he set about doing so is the subject of this book. We will reach far into his personal and administrative papers and examine the organizations over which he presided and the close alliances that he nurtured in the upper echelons of Washington, D.C. His friends and supporters ranged from conservative pastors, corporate leaders, and federal agencies to the nations highly devout commander in chief, Dwight D. Eisenhower. Peales affinity with such natural allies helped to make anticommunismand, subsequently, much of positive thinking and significant currents in psychiatryfervently pro-Christian. Together these factors transformed the nation and its religious life. They reassigned health and well-being as categories under God, and success as the consequence of strong religious conviction. All the while, and quite predictably, public religiosity rose to stratospheric levels.

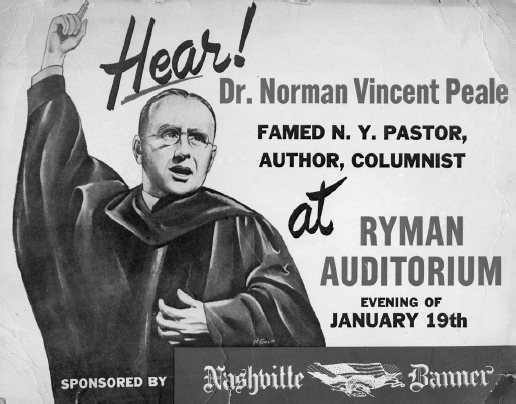

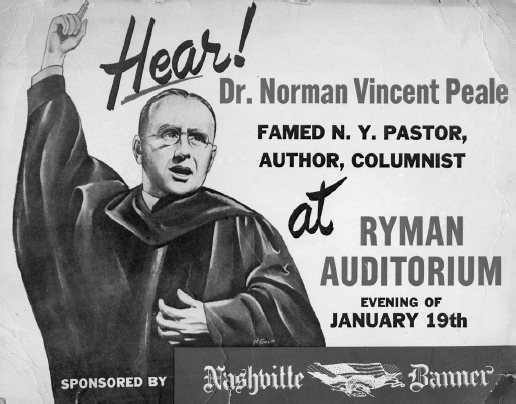

Hear! Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, Famed N. Y. Pastor, Author, Columnist. Poster for talk at Ryman Auditorium, Nashville, January 19, 1951. Norman Vincent Peale Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

Dr. Peale Tells Thousands HereThe Future Belongs To Christ Not Communism, Nashville Banner, January 20, 1951. Norman Vincent Peale Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

There were, granted, ample grounds for concern. Given a decade-long slump blighting the U.S. economy, the war against the Axis powers of Japan-Germany-Italy, a grinding, unwinnable conflict in Korea, and a lengthy, dangerous nuclear standoff with the Soviet Union, insecurity was rampant. These are ominous days days of swift and shocking developments, President Franklin D. Roosevelt warned a joint session of Congress in May 1940, as Germany invaded the Low Countries and France, and Japan readied its air force to attack the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor. As the historian Ira Katznelson observes, Fear about warfare and global violence became a permanent

What was needed, Peale and others believed, were ways to bring energy to despair, to restore a sense of security and unite the country in its beliefs.

As his press coverage shifted to column titles such as Peale Fears Red Aspect of Agitation Is a Token of Un-American Trends, Peale described the nation as undergoing a second revolution, one treating the economic and broader cultural characteristics of the New Deal with almost religious respect.

Peale, by then minister of New Yorks Marble Collegiate Church, was not alone in urging the use of religion in what has since been called a public relations war against the New Deal. Over the next decade, with Peales full support as a member of the advisory board, the organization would exert considerable influence on the way Americans understood themselves religiously.

Peale was without doubt one of the conservative clergymen deployed to discredit Franklin D. Roosevelts New Deal, notes the Princeton historian Kevin M. Kruse.

Nor did the reverends open enthusiasm for Christian world conquest lack an occasional threat to the unreligious or disbelieving. Almost a decade before his friend and admirer J. Edgar Hoover spoke of the need to quarantine communism because of the diabolic machinations of sinister figures engaged in un-American activities, the minister from Ohio warned from his Manhattan pulpit in 1936, The man who

The real enemy. As Cold War tensions mounted in the 1950s and much of eastern Europe succumbed to Soviet occupation, pro-Christian anticommunism in the United States became a popular way of arousing religious sentiment nationally. Representative Louis C. Rabaut, a Democrat from suburban Detroit, summed up the picture in 1954 when telling other lawmakers in the House of Representatives, You may argue from dawn to dusk about differing political, economic, and social systems, but the fundamental issue which is the unbridgeable gap between America and Communist Russia is a belief in Almighty God.

Next page