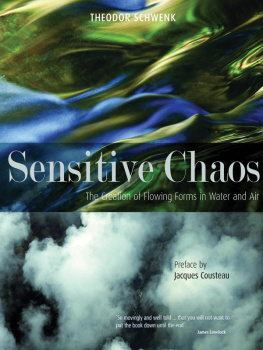

THEODOR SCHWENK (1910-1986) was a pioneer in water research. He founded the Institute for Flow Sciences for the scientific study of waters movement and its life-promoting forces. A prolific writer and lecturer, he contributed original insights to the production of homeopathic and anthroposophic medicines, developed drop-pictures for analyzing water quality and methods for healing polluted and dead water.

THEODOR SCHWENK

SENSITIVE CHAOS

THE CREATION OF FLOWING FORMS

IN WATER AND AIR

Sophia Books

Translated by Olive Whicher and Johanna Wrigley Revised by J. Collis

Illustrations in the text by Walther Roggenkamp

Sophia Books

Rudolf Steiner Press

Hillside House, The Square

Forest Row, East Sussex

RH18 5ES

www.rudolfsteinerpress.com

First English edition 1965

Reprinted 1971, 1976 and 1990

Revised second edition 1996

Reprinted 1999, 2001, 2004, 2008

Originally published in German by Verlag Freies Geistesleben, Stuttgart, in 1962

Verlag Freies Geistesleben 1962

This revised translation Rudolf Steiner Press 1996

The moral right of the author has been asserted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 85584 362 2

Cover by Andrew Morgan

Typeset by DP Photosetting, Aylesbury, Bucks.

Contents

PREFACE

by

Commandant J. Y. Cousteau

Ever since that magical moment when my eyes opened under the sea I have been unable to see, think or live as I had done before. That was twenty-six years ago. So many things happened all at once that even now I cannot sort them all out. My body floated weightlessly through space, the water took possession of my skin, the clear outlines of marine creatures had something almost provocative, and economy of movement acquired moral significance. GravityI saw it in a flash was the original sin, committed by the first living beings who left the sea. Redemption would come only when we returned to the ocean as already the sea mammals have done.

When, in the Islands of Cape Verde, Tailliez and I were caught in the nuptial round of the great silver caranx, we were dazzled by the harmonious fluidity of their ballet: as each fish luxuriously adapted the curves of its body in response to the slightest stir of the surrounding water, the whole school regrouped on the pattern of a whirlpool spiral. In the Red Sea, along the coral reefs, I followed with Dumas the big grey sharks, admiring their noble shape but especially the way every part of their body reacted to the impact of the water of which they were the living expression. On the Corsican shelf, 600 feet below, I watched through the portholes of my diving saucer the long seahounds swiftly gliding close to the slime without ever disturbing the clear water.

Off the island of Alboran, above the forests of gigantic laminarians, I dived at night with Falco in the stream of Atlantic waters rushing into the Mediterranean at a speed of three knots. Under the keel of Espadon we drifted along with our floodlights: all around us there arose from the living sea a hymn to the sensitive chaos. The vast culture medium was swarming with clusters of eggs, transparent larvae, tiny, faintly coloured crustaceans, long Venus girdles which a single gesture could wind at a distance, crystal bells indolently pulsating, turned by our lights into glittering gems. The salps, small barrel-shaped forms consisting of organized water, were joined together into trains sixty or ninety feet long, their transparency punctuated by the minute orange dots which are at the core of each individual.

All that life around us was really water, modelled according to its own laws, vitalized by each fresh venture, striving to rise into consciousness.

These memoriesand many morehave now taken for me a new meaning suggested by the book of Theodor Schwenk. Today it is my privilege to introduce to English readers this remarkable book.

(From the preface to the French edition, 1963)

Foreword

Mans relationship to water has changed completely during the last few centuries. It is now for us a matter of course to have water easily at our disposal for daily use; in the past the fetching and carrying of water involved great effort and labour, and it was valued far more highly. In olden days religious homage was done to water, for people felt it to be filled with divine beings whom they could only approach with the greatest reverence. Divinities of waterthe water gods often appear at the beginning of a mythology.

Human beings gradually lost the knowledge and experience of the spiritual nature of water, until at last they came to treat it merely as a substance and a means of transmitting energy. At the beginning of the technical age a few individuals in their inspired consciousness were still able to feel that the elements were filled with spiritual beings. People like Leonardo da Vinci, Goethe, Novalis and Hegel were still able to approach the true nature of water. Leonardo, who may be considered the first man to make systematic experiments with water in the modern sense of the word, still perceived the wonders of this element and its relationship with the developing forms of living creatures. Natural philosophy in the time of Goethe and the Romantic movement still gave water its place as the image of all liquids and the bearer of the living formative processes. People experienced the fluid element to be the universal element, not yet solidified but remaining open to outside influences, the unformed, indeterminate element, ready to receive definite form; they knew it as the sensitive chaos. (Novalis Fragmente.)

The more people learned to understand the physical nature of water and to use it technically, the more their knowledge of the soul and spirit of this element faded. This was a basic change of attitude, for they now looked no longer at the being of water but merely at its physical value. People gradually learnt to subject water to the needs of their great technical achievements. Today they are able to subdue its might, to accumulate vast quantities of water artificially behind gigantic dams, and to send it down through enormous pipes as flowing energy into the turbines of the power stations. They know how to utilize its physical force with astonishing effectiveness. The rising technical and commercial way of thinking, directed only towards utility, took firm hold of all spheres of life, valuing them accordingly.

But what was at first considered with satisfaction to be a great and final achievement is now calling forth a response from nature that asks for second thoughts, and opens up great questions. Whereas it then seemed profitable and advantageous to dry out swamps and make them arable, to deforest the land, to straighten rivers, to remove hedges and transform landscapes, today it is being realized that essential, vital functions of the whole organism of nature have very often suffered and been badly damaged by these methods. A way of thinking directed solely to profit cannot perceive the vital coherence of all things in nature. We must today learn from nature how uneconomical and shortsighted our way of thinking has been. Indeed, everywhere a change is now coming about; the recognition of a vital coherence among living things is gaining ground. It is being realized that the living circulations cannot be destroyed without dire consequences and that water is

Next page