ii

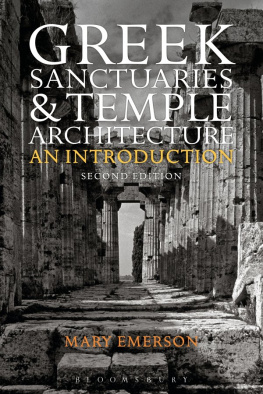

Paestum. Second Temple of Hera with eastern hill

Published 2013 by Trinity University Press

San Antonio, Texas 78212

Copyright 1962, 2013 by Vincent Scully

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Trinity University Press strives to produce its books using methods and materials in an environmentally sensitive manner. We favor working with manufacturers that practice sustainable management of all natural resources, produce paper using recycled stock, and manage forests with the best possible practices for people, biodiversity, and sustainability. The press is a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit program dedicated to supporting publishers in their efforts to reduce their impacts on endangered forests, climate change, and forest-dependent communities.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi 39.48-1992.

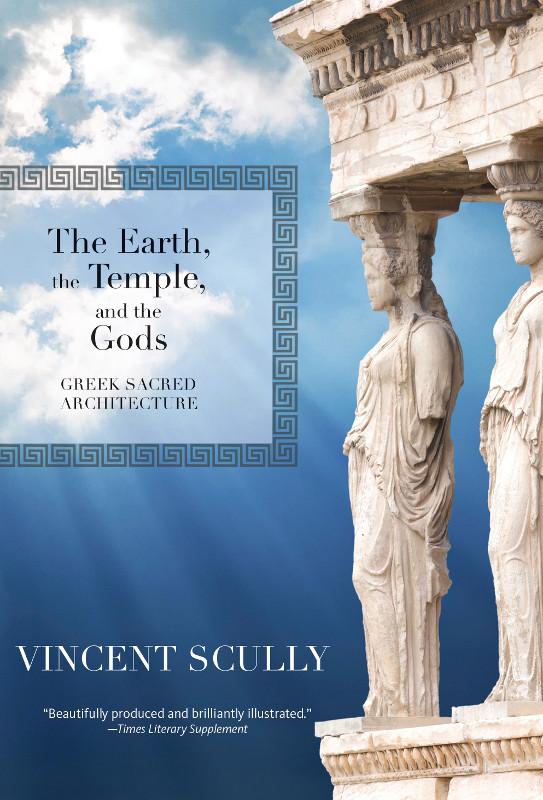

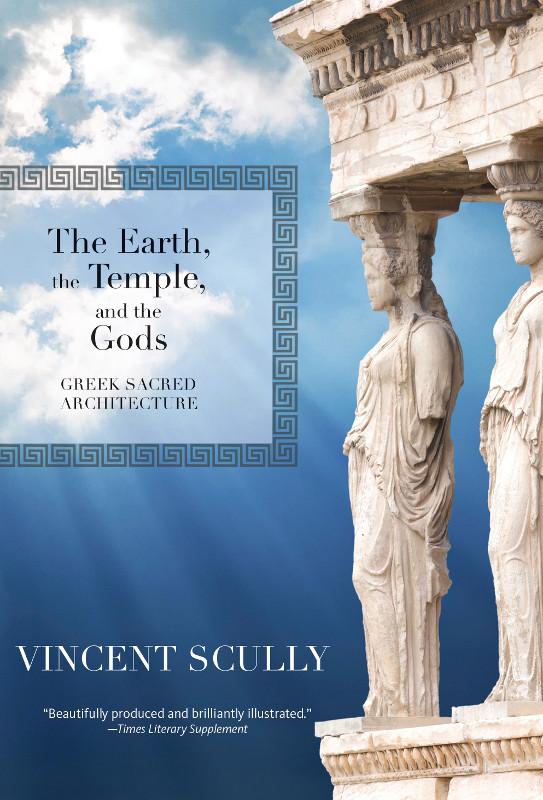

Cover design by Rebecca Lown

Cover illustration: iStockphoto.com/TMSK Studio

Acknowledgment for quotations and illustrations used is made in the Notes and List of Illustrations and here also to the following: A. and J. Picard, Paris; American School of Classical Studies at Athens; Art Reference Bureau, Inc.; A. Asher and Co., Berlin; Atlantis Verlag, Zrich; Batsford, London; British Museum, London; F. Bruckmann K. G. Verlag, Munich; Witter Bynner, Santa Fe; Clarendon Press, Oxford; Deutsche Archologische Institut; Direktion der Antikensammlungen, Munich; Editions Cahiers DArt, Paris; cole Franais dAthnes; Faber and Faber, London; Heinemann and Co., London; Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt-am-Main; Librairie Gnrale, Paris; Macmillan, London; Mansell Collection, London; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Ministry of Works, London; New Directions, New York; New York University Press; M. Parrish, London; Penguin Books, Hammonsworth, Middlesex; Princeton University Press; Spazio, Rome; University of Chicago Press; Verlag der K. B. Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich; Verleg Gebr. Mann, Berlin; Kurt Vowinckel Verlag, Berlin; Mrs. Alan Wace, Athens; Walter de Gruyter and Co., Berlin.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Scully, Vincent, Jr., 1920

The earth, the temple, and the gods: Greek sacred architecture / Vincent Scully. Revised Edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9781595341761 (pbk.)

ISBN 9781595341778 (ebook)

1. TemplesGreece. 2. Temples, Greek. I. Title.

NA275.S3 2013

726'.1208dc23

2013012450

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

v

For F.E.B. and E.V

and

Daniel, Stephen, and John

vi

The Gods.

Resolved by the Council and the People on the motion of Themistokles, son of Neokles, of the deme Phrearrhoi: to entrust the city to Athena the Mistress of Athens and to all the other gods to guard and defend

Michael H. Jameson, A Decree of Themistokles

from Troizen, Hesperia, 29 (1960), 198223.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

viii

ix

PREFACE TO THE 1969 EDITION

I am grateful to the readers of this book, whose interest has occasioned a paperback edition, and to its reviewers for the generosity with which it has almost universally been received. It is not easy to set aside firmly seated preconceptions in order to look at old material with fresh eyeshardest of all to face facts which, if true, are so obvious and simple that they should patently have been recognized long before. Many scholars have apparently been willing to extend such recognition now. This is not the place to take issue with those who may have been unprepared to do so. The reader interested in polemic is referred to my letter in the The Art Bulletin, 46 (March, 1964). Still, a serious problem of method apparently exists here for those classical archaeologists who were trained to catalogue data according to positivistic criteria based upon a contemporary or, more likely, a nineteenthcentury model of reality. Landscape shapes, for example, simply do not exist for them artistically in other than picturesque terms. Hence they are blind to their sculptural forms and insensitive to their iconography, and so can neither trace their series nor assess their meaning for the Greeks. There is nothing strange in this. Human beings perceive pragmatically only within a framework of symbolic prefiguration. For this reason the human eye always needs to be trained and released to see the meaning of things. It can usually focus intelligently only upon what the brain has already imagined for it, and it faithfully reflects the timidity of that culturebound, sometimes occluded, organ.

Modern culture has little connection with the earthor, rather, normally fails to perceive a connection with it. But for the Greeks the earth embodied divinity. We, on our part, must make the effort of historical imagination that is required if our eyes are to see according to some dim approximation of the Greeks inner no less than their outer light.

Here the Americanist archaeologist, with his anthropological intention and avoidance of ethnocentricity, can be of help, both generally in the intended completeness of his interpretive method (Walter W. Taylor, A Study of Archeology, Carbondale, 1967), and specifically in terms of the recognition of sacred landscapes (John Peabody Harrington, The Ethnogeography of the Tewa Indians, in the 29th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 19071908, Washington, 1916).

I should like to express my thanks to the Yale University Press for proposing this edition and to Praeger for carrying it out and for including in it my later articles on Aeolic capitals and x some additional sites, which originally appeared, respectively, in The Architectural Review (February, 1964), and the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (May, 1964). My sincere thanks are also due those publications for permitting reprinting here. The book, with a few corrections, rephrasings, and new photographs, has otherwise been left much as it was. The quotations used as chapter headings and so on have been retained, though they were chosen in part for their grace of expression in English and have therefore been criticized for their comparative freedom of translation. The interested reader may consult the Greek in any event, though where a Greek word is central to the topic it has of course been translated as strictly as possible. Yet it should be obvious that the structure of my thesis is, and has to be, fundamentally visual rather than philological.

I wish, it is true, that I might have been able to rewrite more of the text. The argument would have remained the same, but some sites, such as Olympia, could have supported a much more extended discussion of their sculpture and associated painting and literature. I should have particulary liked the chance to analyze a number of archaic temples in direct sculptural comparison with a number of kouroi. More references to sculpture and painting would have been useful throughout, since I think that one of the results of this study has been to illuminate the significance of the general development of Greek art from its early sculpturally real to its later pictorially illusionistic premises. There is, I believe, a good deal to be learned along this line about the relationship between art and nature in general.

Next page