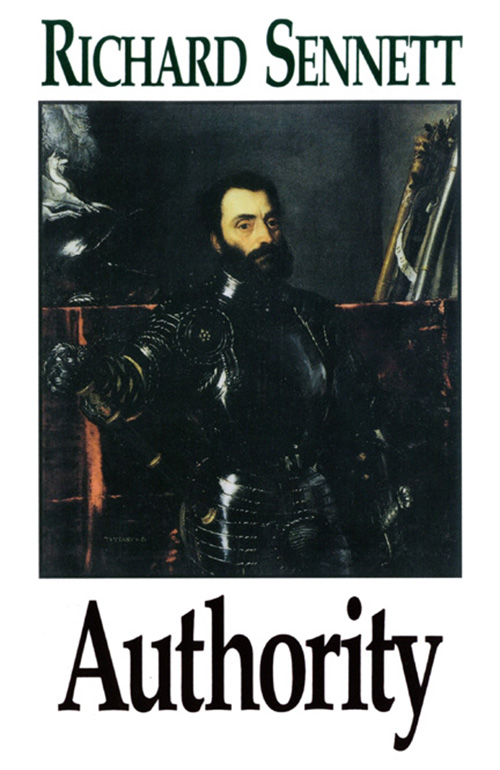

By Richard Sennett

in Norton Paperback

The Conscience of the Eye:

The Design and Social Life of Cities

The Fall of Public Man

The Uses of Disorder:

Personal Identity and City Life

Authority

AUTHORITY

Richard Sennett

Authority

W. W. Norton

New York London

Copyright 1980 by Richard Sennett

First published as a Norton paperback 1993

by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Harvard

Business Review for permission to reprint

an excerpt from The Dynamics of Subordinancy

by Abraham Zaleznik (May-June 1965). Copyright

1965 by the President and Fellows of

Harvard College. All rights reserved. Reprinted

by permission of the Harvard Business Review.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Sennett, Richard. (Date)

Authority.

Includes index.

1. Authority. I. Title.

HM271.S36 1980 303.36 79-3492

ISBN 978-0-393-31027-6

ISBN 978-0-393-35093-7 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

For Dorothy Sennett

I am that father whom your boyhood lacked and suffered pain for lack of. I am he.

This is not princely, to be swept away by wonder at your fathers presence. No other Odysseus will ever come, for he and I are one, the same....

Odyssey, Book XVI,

translated by Robert Fitzgerald

T his book began as a Sigmund Freud Memorial Lecture at the University of London in 1977. I wish to thank the trustees of the Lectureship, and in particular Professor Richard Wollheim, for inviting me. Subsequent research and writing of this book were made possible by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

Many friends helped me with advice and criticism. I would like to thank especially Susan Sontag, Loren Baritz, Thomas Kuhn, Daniel Bell, David Rieff, Rosalind Krauss, Anthony Giddens, and David Kalstone.

As always, Robert Gottlieb and the staff of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. have been sympathetic and efficient.

R.S.

T his book is the first of four related essays on the emotional bonds of modern society. I want to understand how people make emotional commitments to one another, what happens when these commitments are broken or absent, and the social forms these bonds take. It is easier to see the emotional commitments made in a family than in a factory, but the emotional life of a large milieu is equally real. Without ties of loyalty, authority, and fraternity, no society as a whole, and none of its institutions, could long function. Emotional bonds therefore have political consequences. They often knit people together against their own interests, as when a people feel loyalty to a charismatic leader who takes away their liberty. Occasionally the need for satisfying emotional relations will turn people against institutions they feel are inadequate. Such complex relations between psychology and politics are the subject matter of the four books in this study.

The present essay is about authority; the second will be about solitude, the third about fraternity, the fourth about ritual. The bond of authority is built of images of strength and weakness; it is the emotional expression of power. Solitude is the perception of being cut off from other people, of a bond missing. Fraternity is based on images of likeness; it is an emotion elicited by the sense of us, nationally, sexually, politically. Ritual is the most passionate, least self-conscious bond of all; it is an emotional unity achieved through drama. As the overall project progresses, I shall correlate these four subjects, but each book is intended as an independent essay.

The word bond has a double meaning. It is a connection; it is also, as in bondage, a constraint. No child could prosper without the sense of trust and nurturance which comes from believing in the authority of its parents, yet in adult life it is often feared that the search for these emotional benefits of authority will turn people into docile slaves. Similarly, fraternity is a connection among adults which can easily become a nightmare: it can provoke either hostile aggression against outsiders or an internal struggle about who really belongs. Solitude seems a lack of connection and therefore a lack of constraint. But it can be so painful that people will blindly commit themselves to a marriage, a job, or a community, and yet find that in the midst of others they remain alone. A ritual unifies, but the sentiment of unity is strange because it disappears the moment the ritual ends.

One result of the ambiguity of emotional bonds is that they are seldom stable. That instability is captured in the root meaning of the term emotion. Aristotle, in De Anima, spoke of emotion as the principle of movement in human experience; the Latin root of the word is movere, to move. But the origins of the word also suggest a larger meaning for emotion than sheer instability. Change occurs in what we feel, Aristotle wrote, because jealousy, anger, and compassion are the results of sensations reflected upon. They are not just sensations; they are sensations we have thought about. This process allows us to act in the world, to affect and to change it. Were we not to feel, we would not be fully awake, Aristotle wrote, and very little would happen in our lives.

This seemingly common-sense notion has not been a dominant one in the history of psychology. Many of Aristotles contemporaries thought emotions were visited on men by the gods; this view reappeared in the Middle Ages, so that lust was the voice of the Devil speaking, compassion an echo of Gods voice of love for man, and so on. Descartes wrote a treatise on emotion which revived Aristotles ideas, but most of his scientific contemporaries were replacing medieval superstitions with concepts of emotion as purely physiological states, as in the idea of bodily humors. Modern psychology, up to quite recently, was prone to separate cognition and affect, thinking and emotion. In its early history, psychoanalysis had a poorly developed theory of emotions, and the range of emotions in the psychoanalytic vocabulary was more primitive than the range of emotions in an ordinary adults experience.

All this has changed in the last generation; Aristotles view that emotion is a joint product of sensing and thinking has again come to the fore in various ways. In continental psychology, this view appears in the work of Jean Piaget, in the Anglo-Saxon world in the writings of Jerome Bruner. In psychoanalysis, this unified view dominates the writings of Roy Schafer and Charles Rycroft. Philosophic interest in the concept of emotion was reawakened by Suzanne K. Langers Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling, and explored in more disciplined ways in many of the writings of Jean-Paul Sartre. It could be said of this new view generally that it seeks to understand anger, jealousy, and compassion as interpretations people make of events or other people. The sense of this in English is conveyed by the question What do you feel about him? Judgement and reasoning are ingredients in coming to have feelings about another person. There is also a moral dimension to this psychological view. Images like blind passion or blind ambition suggest the person feeling them was so over-whelmed by emotion as not to be responsible for his or her actions. This, the new view would argue, is deceptive; emotion is always an act of fully engaged interpretation, of making sense of the world, and therefore we are always legally and morally responsible for what we feel.

Next page