THE SELF POSSESSED

the self possessed

DEITY AND SPIRIT POSSESSION IN SOUTH ASIAN LITERATURE AND CIVILIZATION

Frederick M. Smith

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

NEW YORK CHICHESTER, WEST SUSSEX

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2006 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-51065-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smith, Frederick M.

The self possessed : deity and spirit possession in South Asian literature and civilization / Frederick M. Smith.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-231-13748-6 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 0-231-51065-9 (electronic)

1. Spirit possessionSouth Asia. 2. Spirit possession in literature. 3. Sanskrit literatureHistory and criticism. 4. TantrismSouth Asia. 5. Spirit possessionHinduism. I. Title.

BL1055.S63 2006

| 133.4260954dc22 | 2005056030 |

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

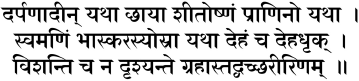

As a reflection is to a mirror or other similar surface, as cold and heat are to living beings, as a suns ray is to ones gemstone, and as the one sustaining the body is to the body, in the same way seizers enter an embodied one but are not seen.

SURUTA SAHIT 6.60.19

This work is dedicated to the memory of the late Pratap Bhagwandas Mody of Bombay, who demonstrated artfully and convincingly that we are never quite alone.

CONTENTS

T HE WRITING OF THIS VOLUME TOOK ME BY SURPRISE. I never envisaged it as part of my research program until it began to form a life of its own. Eventually, it grew from childhood to adolescence and, typical of adolescence, began to exact unreasonable demands on my resources, including time, place, and modes of thought. Having now achieved maturity, it demands to be set free. On the whole, I would have preferred to be in India translating Sanskrit and examining manuscripts, rather than working on a project like this that imposed on me a new and very different set of intellectual, psychic, and even physical demands. As it turned out, I was forced to examine worlds of thought and theory that I had always suspected lay in wait, less quietly than I appreciated, to ensnare me, while the project unceasingly transgressed boundaries I kept setting on it. Its conception and infancyI thoughtlessly intended to abandon it in childhoodtook the form of papers delivered at annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion in 1992, the American Oriental Society in 1993, and the Indic Seminar at Columbia University in 1994. My intention in these papers was to examine a few of the semantic issues surrounding some of the key terms for possession that I saw repeated in Sanskrit texts of many different periods and genres. I foolishly believed that I could accomplish this in ten, twenty, or thirty pages. Soon enough, however, I discovered the vast ethnographic literature of possession in India and became almost hopelessly entangledand gridlockedin the theoretical issues surrounding it. This is discussed in due course, but I must confess here that my reading of possession in modernity had a much greater impact on my reading of possession in antiquity than I had expected or desired. Instead of a paper on possession in antiquitythe initial scope of the projectthis has become a work more generally on possession in South Asian culture over a long span of time.

After several years, at first intermittently, of data gathering and absorbing stories of possession, then reading and reflecting on theories of possession, and finally engaging it actively, I have arrived, with this book, at a meditation, a perilously intimate one, on personhood, which is sometimes, though not always, contiguous with selfhood. As the title of the book suggests, I find myself attempting to reconcile in this project the self, possessed, with a presentable veneer of self-possession. In this way, the final product has also become a meditation on embodiment and incarnation, gain and loss, transformation and transition, and tradition and imagination, which, my friend Robert Beer reminds me, must become the same thing (1988:9). However it beganand the raison dtre of scholarship is often contested, perhaps especially within the mind and body of the scholar him or herselfit was, upon reflection, inspired by the constant, elusive, and very personal conundrum of embodiment, by a sense of the irreducible strangeness of life, by the shock of an eternally mutating present and presence when we seek only past and future permanence, which is to say by the trauma and bewilderment of continuity when we seek resolution and termination. This was aided by a vision of the simultaneity of multiple selves clamoring for dominance, propriety, order, and voice as they succumb to the inexorable force of entropy, by dreams pushed aside incomplete and irretrievable by the disappointment of awakening, and by awakening to (and within) the disappointedness of dream. In short, the process of creating this book has been a long and complicated exorcism.

If my selection of material appears planned but extravagant, the reason is that the planning came to life as a learning process, like perfecting a rga: I found a few unique scales and constantly improvised on them. Thus, the extravagance could never be exhaustive. The material turned out to be much more extensive than I initially expected. In many key places, in dealing with the Mahbhrata, Tantra, and bhakti texts, for example, I was forced to be illustrative and selective. As a friend, a veteran of many books, told me (paraphrasing W. H. Auden, as I recall) when I was about three-quarters done, this is the kind of book that cannot be completed but, instead, should be abandoned. The lesson for me was that both data and knowledge can be infinite, especially as they are swept up in an ever-expanding vision with ever-increasing dimensions and vocalities. The evidence of the multidimensionality and multivocality of possession that I have brought to bear on the topic is more than I had ever hoped to find or thought was even possible. Many readers will still say that I left out this or that, especially from ethnographies or modern autobiographies, or could have interpreted something differently, that I should have attended more to feminist perspectives or psychoanalytic theory. I must also mention that our knowledge of Tantra from the mid-first millennium through the first few centuries of the second millennium C.E. is rapidly expanding, in great measure because of the efforts of Alexis Sanderson and his students at Oxford University. Doubtless, there will soon be much more to say about possession in tantric literature that will add considerably to what I have written in , and may force new paradigms on the notion of possession itself as it was configured historically in India. Nevertheless, for me, this exercisewhatever I have adduced on the topichas turned religion, particularly as observed in South Asia, on its head, as the material ultimately argues against much of what is stated in standard textbooks. If even a tiny amount of that is transmitted to the reader, this project will have been worth the effort.

I should say a few words here about the study of possession. In India and elsewhere, the field has been dominated by compartmentalized ethnographies and, less often, by histories of possession in specific lineages or local cultures. No syncretic history or synoptic account of possession in India has been attempted. While my intention here is to locate and capture such a history, I have tried to keep in mind the problems associated with master narratives and endeavored to avoid them. Even if I were dedicated to a single theoretical model (and it will soon become obvious that I am not), two things would still parry any attempt to create such a master narrative: the sheer variety of the textual and ethnographic source material, and the delicacy with which the layers of their connections must be handled. I have been constantly aware of the pitfalls of both subjectivity and objectification that confront both scholars and participants who think about and live with possession. This inspires in me a certain trepidation, because it sharpens rather than occludes the necessity to define and delimit, to construct and deconstruct, to know when to intervene and when to leave alone, to know how strongly to invoke situated histories, to know when to allow tradition and imagination to merge, and to feel comfortable if all my data and conclusions are not scrubbed clean of contradiction. Nevertheless, I take full responsibility for lapses in clarity, errors in judgment, and oversights in the use of material.