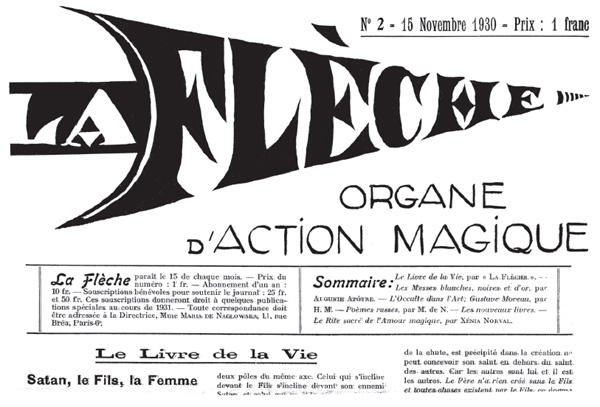

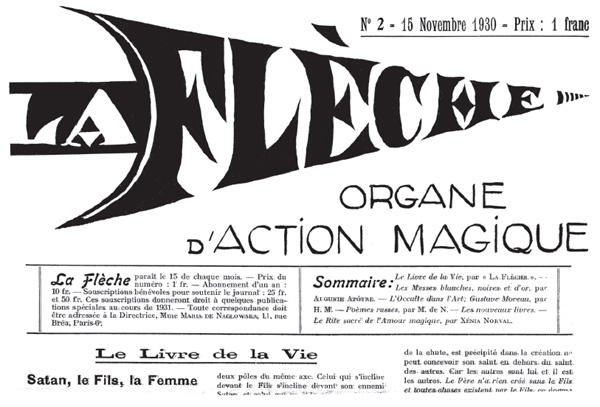

La Flche No. 2, the rarest of all the issues of La Flche

INTRODUCTION

THE ORGAN OF MAGICAL ACTION

Donald Traxler

If we could go back to the Paris of the early 1930s and stroll the streets of Montparnasse, we might easily meet an attractive Russian woman sitting in a caf surrounded by occultists. Or, we might see her selling her little newspaper in front of the caf. That woman was Maria de Naglowska, and the little monthly newspaper she was selling, of either eight or sixteen pages depending on her finances at the time, was La Flche, Organe dAction Magique. In English, The Arrow, Organ of Magical Action. If the reader guesses that the title may have been a phallic reference, the reader is correctand it was intended that way.

Shocking? Probably not so much for that time and place or for that woman who was herself considered shocking by many.

Maria was influential among the Surrealists, and they seem to have influenced her own writing. Naglowskas sessions are said to have been attended by the avant-garde and the notorious of the time, including Man Ray, William Seabrook, Michel Leiris, Georges Bataille, and Andr Breton. Jean Paulhan, for whom LHistoire dO was written, is also said to have attended. I have not yet been able to trace these often-made claims to reliable, original sources, so for now, they should be regarded as hearsay. An example of the difficulty of verifying the other names is the claim made for both Bataille and Paulhan in Demons of the Flesh by Nikolas and Zeena Schreck. Unfortunately the only supporting reference the Schrecks give for Naglowska is to an earlier article by Nikolas Schreck. Their bibliography does not include anything by Bataille, Paulhan, or Naglowska (although they mentioned Naglowska seventy-four times in their book), and the claim is not supported in any footnote or endnote. It must, therefore, be considered hearsay, at least for now. In the case of William Seabrook, his connections with Man Ray and Michel Leiris are well known and documented by both their and his own writings. Whether Seabrook did indeed attend Naglowskas sessions is not proven as far as I am concerned. I have read his autobiography and the biography written by his second wife, Marjorie Worthington, and found nothing. The only indication that Seabrook was aware of Naglowska, other than his association with Man Ray and other surrealists, is in a Wambly Bald piece in the Paris edition of the Chicago Tribune for November 3, 1931. A perhaps telling fact, though, is that both Naglowska and Seabrook studied philosophy at the University of Geneva before the First World War. It is interesting to note that in Marjorie Worthingtons biography of Seabrook she states that he considered himself a Catholic (although he was the son of a Protestant minister and had been raised as a Protestant). This self-identification, apparently without external practices, could have been due to Naglowskas influence.

We know that surrealist poet and painter Camille Bryen was a member of Naglowskas group from the short biography titled La Sophiale by Marc Pluquet.

The writer Ernest Gengenbach also appears to have been a part of Naglowskas group according to the Foreword in the Deveney and Rosemont book.

Until recently, Maria de Naglowska was almost unknown to the English-speaking world. Those who knew her at all probably knew her as the translator of Paschal Beverly Randolphs Magia Sexualis, for which she did far more than translate. Now, a realization is growing that Naglowska was an important religious innovator, an interesting thinker, and a fine writer. The scandalous image is something that she seems to have carefully cultivated for her own purposes.

The present volume, the fifth in a series of Naglowska translations, reinforces what we learned from the earlier ones, and shows another of her facets: that of the journalist. The quality of Marias writing should not surprise us, because all her adult life she lived by writing. The difference is that unlike the journalism that supported her family, in La Flche and in the other books published in this series the subject matter was spiritual, sexual, and magical.

Who was this strange woman who peddled her newspaper on the streets of Montparnasse?

Maria de Naglowska was born in St. Petersburg in 1883, the daughter of a prominent family. She went to the best schools and got the best education that a young woman of the time could get. She fell in love with a young Jewish musician, Moise Hopenko, and married him against the wishes of her family. The rift with Marias family caused the young couple to leave Russia for Germany and then Switzerland. After Maria had given birth to three children, her young husband, a Zionist, decided to leave his family and go to Palestine. This made things very difficult for Naglowska, who was forced to take various jobs as a journalist to make ends meet. While she was living in Geneva she also wrote a French grammar for Russian immigrants to Switzerland. Unfortunately, Naglowskas libertarian ideas tended to get her into trouble with governments wherever she went. She spent most of the 1920s in Rome, and at the end of that decade she moved on to Paris.

While in Rome Maria de Naglowska met Julius Evola, a pagan traditionalist who wanted to reinstate the pantheon of ancient Rome. Evola was also an occultist, being a member of the Group of Ur and counting among his associates some of the followers of Giuliano Kremmerz. It is said that Naglowska and Evola were lovers. It is known, at least, that they were associates for a long time. She translated one of his poems into French (the only form in which it has survived), and he translated some of her work into Italian.

While occultists give a great deal of weight to Naglowskas relationship with Evola, it is clear that there must have been other influences. Some believe that she was influenced by the Russian sect of the Khlysti, and some believe that she knew Rasputin (whose biography she translated). Maria, though, gave the credit for some of her unusual ideas to an old Catholic monk whom she met in Rome. Although Maria said that he was quite well known there, he has never been identified.

Maria said that the old monk gave her a piece of cardboard, on which was drawn a triangle, to represent the Trinity. The first two apices of the triangle were clearly labeled to indicate the Father and the Son. The third, left more indistinct, was intended to represent the Holy Spirit. To Maria, the Holy Spirit was feminine. We dont know how much was the monks teaching and how much was hers, but Maria taught that the Father represented Judaism and reason, while the Son represented Christianity, the heart, and an era whose end was approaching. To Maria, the feminine Spirit represented a new era, sex, and the reconciliation of the light and dark forces in nature.

It is mostly this idea of the reconciliation of the light and dark forces that has gotten Maria into trouble, and caused her to be thought of as a Satanist. Maria herself is partly responsible for this, having referred to herself as a satanic woman and used the name also in other ways in her writings. Evola, in his book The Metaphysics of Sex, mentioned her deliberate intention to scandalize the reader. Here is what Naglowska herself had to say about it.

Next page