Introduction

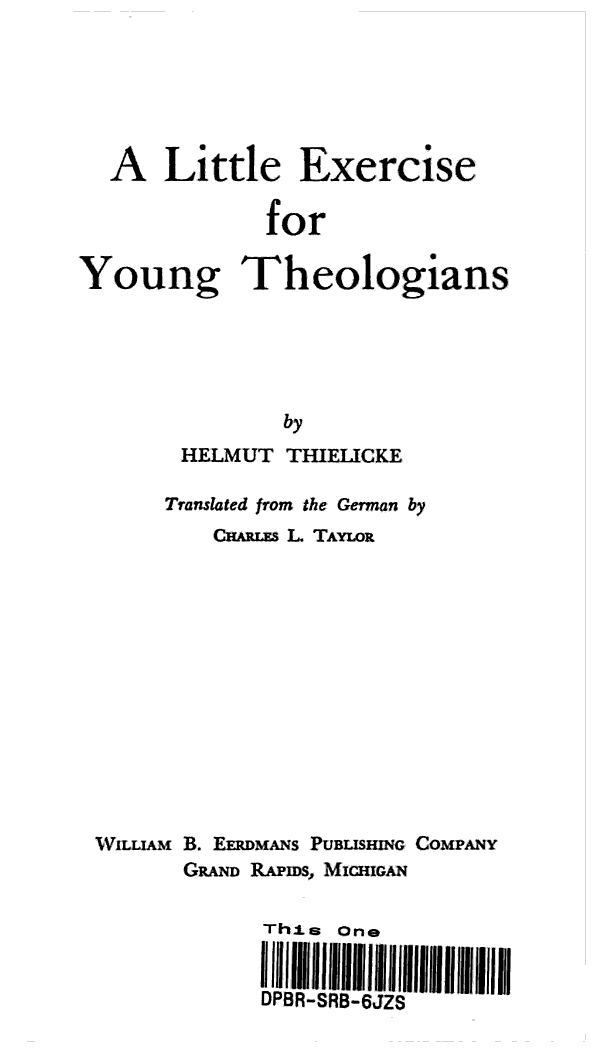

Think, if you will, of this modest book as if it were a greeting card. It can serve best in its first purpose: as a bon voyage greeting to a person venturing for the first season into theological studies. Just as well, the book could say "Happy Anniversary" to a practical parson humble enough to look back, to measure himself against his intentions. Then, again, it may be needed as a "Get Well" where there is hope for a pretentious theologian or in radical instances as a sympathy card to someone who has forgotten the whole excitement and promise of the theological task.

In the paragraph I have just written some version of the term "theology" appeared three times. Thus it carefully reproduces the intention of the book: in clear and forceful language the author sets out to speak of the difficult language of theology. If it is used to greet a young theologian, the book will not soon be placed back among his souvenirs. To begin to exhaust its meanings, one must consult it again and again. The author expects the budding theologian to take from it good counsel.

Before anyone accepts counsel he naturally does well to examine the credentials of the counselor. By what right does he speak? Will he preach at me or insinuate his opinions into my consciousness? Will he pontificate or will he be condescend ing? In this instance, does he know what theology and young theologians are all about?

Concerning few people in the Christian world would one have fewer hesitancies than we reserve for Helmut Thielicke. He wears several mantles, and they fit well. As recent Rector of the University of Hamburg he was obliged to wear the business suit of the secular administrator as he calls himself in these pages as well as the historic academic garb of that post. As a practicing theologian, he may wear the robes of professorial office in order to provide the setting for a learned lecture on Christian ethics. Most readers could picture him best in his preaching robe: some number him among the greatest preachers in the world today. It is well known the covers of German news magazines can testify that he fills a very large church in "secularized" Hamburg twice a week. His translated sermons, now running into a number of volumes, are among the few that preachers read for their own nourishment. Finally, we picture him as world-traveler or storyteller in his corduroy sport coat. He is at home in all these roles: each equips him for the tones of voice he uses here.

A scholarly, intense, concerned man, Thielicke wins the confidence of his hearers. He says some things to young theologians here which few other people could say with such sting and still such grace and healing. No doubt in the ozoned reaches of Continental theology there are more astute theologians than he. No doubt in the broad pavements of American practical church life there are better administrators. But few are his peers for synthesizing respectable scholarly inquiry and informed practical churchmanship. The synthesis is sorely needed in Europe today and I am sure it is equally welcomed, from a different angle, in the Western hemisphere.

Born in 1908, pursuing a conventionally broad and deep German theological education, Thielicke underwent a personal crisis in the 1930s. Then, as his career blossomed, he was to be tried by the terror of National Socialism. He won a new kind of right to speak by his opposition to Nazism. Since World War II he has come to prominence. Experienced theologians or parsons who pick up this book will no doubt already have on their shelves several of the titles which reveal his range of interests: Between God and Satan, The Silence of God, Our Heavenly Father, The Waiting Father, How the World Began, Christ and the Meaning of Life, Nihilism, or his informed reply to Rudolf Bultmann. The newcomer to theology will soon be possessing and reading these as well as learning to plow through the German of his massive Ethics (or learning patience to await the translation!). Thielicke writes as rapidly as some of us read.

The biographical accent of these first pages is not intended to embarrass the author, but to show how the particular set of virtues he combines is rarely come by, sorely needed, and essential for the task before him: the giving of advice. I should not wish to make it seem that theology is to him a superficial task in either the intellectual or moral sense. You will see him define it as "reflection" on the one hand, or as "conscience" on the other. His work reveals an inner consistency that certi fies the impression that Thielicke's many expressions come from one radiating center.

Of course, the author's assets bring with them certain liabilities. His overpowering style sometimes obscures the validity of alternate viewpoints. For instance, his Christian consciousness prematurely overpowers the nihilist whom he would understand in his book on nihilism. Or, again: one can read his exegesis of a parable and be awed by it. Then, on consulting the text and the various other careful inquiries concerning its meaning (say, in Joachim Jeremias or Charles H. Dodd), a student may become convinced that "scientifically" the others may be more faithful to the parable. Thielicke's intuition and instinct are so colorful that other levels of interest and accuracy may suffer. You may ask, "Why fault Thielicke for the intensity of his analysis and expression?" Still, it is possible that a person of great consistency and articulateness will have an unfair advantage over those who bring quieter theological disciplines to their task. The reader can make the test himself; the publishers provide clean margins for notes and arguments. A book of advice should be taken that way.

Dr. Thielicke calls this "A Little Exercise for Theologians"; in it he goes about his assigned task of opening a seminar in his own discipline. The publishers have, I believe wisely, kept the work's personal character in mind. They have retained a number of references which mean less to an American audience than to the original hearers. But thus we get a sense of eavesdropping on a lecture we should like to have attended in person. This removes the sense that we might be offered here some gratuitous advice. In naming this an "exercise" Thielicke has in mind the format of Loyola's Spiritual Exercises and other books of Christian self-discipline. That is how I would describe this book: it is a lesson in theological self-discipline. It may be only a "little exercise" in a profound field; it may be Eine kleine Nachtmusik, or a grace note alongside the De Profunda of the theological library, a pen-sketch to be left at the foot of the mural. But in its modest way it can inform the whole. An "aside" whispered in a stage play can deal a glancing blow to every other direct line. Here is Thielicke's aside to a theological audience.

A temptation often comes to one who introduces a book to anticipate or repeat its contents. Instead, I would rather converse with its argument. Does the Christian who is becoming or has become a self-conscious theologian in America have the same problems as those cited here? On the Continent so it is said the theologian lives more in the ivory tower than does his American counterpart; the activist there is less activistic; theology there has less to do with the life of the church than with rigorous, scientific, respectable discipline. In evangelism, stewardship, pastoral care, administration, the American churchman leads the field.