Copyright 1999 by Thomas L. Thompson.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part

of this book may be reproduced in any manner without permission

except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and

reviews. For information, address Basic Books,

New York, NY

Preface: the academic debate

At the moment of writing this preface, I am preparing to go to Lausanne for a meeting of the European Seminar on Historical Methodology of the History of Israel, and reading the papers to be discussed at the seminar. The topic is the exile as a subject of history. The issues centre on how we are to correlate the many Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian texts relating to war, the destruction of cities and the deportation of peoples throughout their empires, the growing archaeological evidence from Palestine, and the wide variety of biblical traditions that deal with themes of destruction, exile and return, but rarely of a period of exile itself. Half of the papers produced for the seminar share much the perspective of this book. Each of them, in its own way, points out difficulties in reading the biblical narratives about deportation and return as if they were historical. They point to the lack of a story in the Bible which tells us of an Israel or a Judah in exile. While they express few doubts that an exile must have occurred, they question whether a history of this exile can be written. The other half of the papers disagree strongly and argue that a history of the exile is at least possible. No one, however, proposes that the Bibles traditions provide us with adequate evidence for that history. As I read through these papers, I cannot help thinking about the changes in our approach to the Bible and its relationship to archaeology that have come about over the past twenty-five years. Long past is the assumption that ancient history can, be written by merely paraphrasing or correcting the stories of the Bible. It has rather become quite difficult to understand these stories as recounting events from their authors past.

It would be ingenuous of me to pretend that this book on the subject is uncontroversial. For me, the debate began as early as in the late 1960s and was first voiced in a doctoral thesis started in 1967 at the University of Tbingen and completed in 1971. My original thesis stemmed from the idea that, if some of the narratives about the Hebrew patriarchs could in fact be dated historically to the second millennium BCE, as nearly all archaeologists and historians then believed, I should be able to distinguish the earliest of the biblical stories from a later expanded tradition.

When I first began this work, I had been so convinced of the historicity of the tales about the patriarchs in Genesis that I unquestioningly accepted parallels that had been claimed with the Late Bronze Age family contracts found in the excavations of the ancient town of Nuzi in northern Mesopotamia. It was therefore all the more upsetting when, in 1969, after more than two years work, it became clear that the family customs and property laws of ancient Nuzi were neither unique in ancient Near Eastern law nor implied by the Genesis stories. Many of these contracts had been misread and misinterpreted. At least one contract had been mistranslated with the purpose of creating a parallel with the Bible. The entire claim of Nuzi parallels to the patriarchal customs had been a thinly veiled fabrication, a product of wish-fulfilment. An entire social world had been created which had never existed.

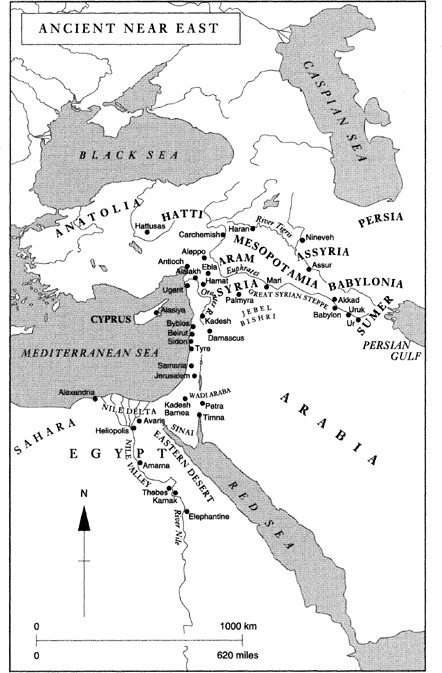

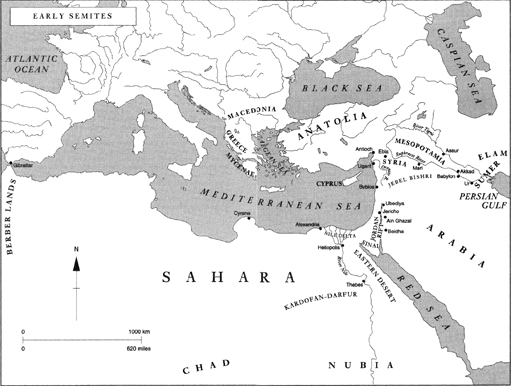

This led to a discussion of the larger question of history and the patriarchs generally, I went on to review the central arguments that had been used to create and support the patriarchal period. The single most important argument had been a very complex Amorite hypothesis, asserting a nomadic migration of West Semites out of the Arabian desert, which disrupted the established agricultural civilizations of the fertile crescent late in the third millennium BCE and developed new settlements from Southern Mesopotamia to the Egyptian Delta. This related nearly every important text find from the third and second millennium to the Bible and to Palestine: whether from Ur, Babylon, Mari, Amarna, Ugarit, Egypt, Phoenicia, or from Palestine itself. These arguments for Amorite migrations and for the existence of a patriarchal period in the history of the ancient Near East also collapsed. They were often arbitrary and wilful. Scholars had taken for granted what they set out to prove. What was presented as the assured results of decades of science and scholarship amounted to careless assertions.

The dissertation was finished in late 1971. Reactions to it were strong. I found it impossible to get my PhD in Europe or to publish my book in the United States. As things worked out, the book was eventually published in Germany in 1974 and I was able to receive my degree from Temple University in Philadelphia in 1976.

The arguments against the historicity of the patriarchal narratives were strongly confirmed by the independent publication in 1975 of the Canadian scholar John Van Seters Abraham in History and Tradition. Van Seters book took the argument even further by showing that the biblical stories themselves could not be seen as early, but must be dated sometime in the sixth century BCE or later. In 1977, John Hayes and J. Maxwell Miller published. Israelite and Judaean History, a large volume of essays written by a number of younger scholars, in which current historical research on each successive biblical period was reviewed. It was now clear that the previous confidence in the view that the Bible was an historical document was collapsing. Widespread doubt was expressed about the historicity not only of the patriarchs of Genesis, but of the stories about Moses, Joshua and the Judges as well. These historians first felt confident in speaking of history when dealing with the period of Saul, David and Solomon.

While Van Seters late dating of the Pentateuch received strong support in Germany and his work led to radical changes in our understanding of these early books of the Bible, the mid-Seventies also saw the publication of a number of new and innovative journals that have changed the direction of research across the entire field of biblical studies. The