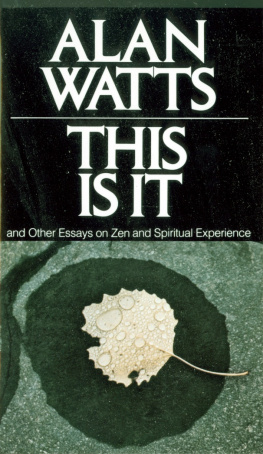

First Vintage Books Edition, April 1973

Copyright 1958, 1960 by Alan W. Watts

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., in November 1960.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Watts, Alan Wilson, 1915

This is it.

Reprint of the 1960 ed.

1. Mysticism 2. Zen Buddhism. I. Title.

[BL625.W35 1973] 294.3 4 72-8394

eISBN: 978-0-307-78432-2

v3.1_r1

TO ANN

daughter and dancer,

with love

CONTENTS

1

This Is IT

2

Instinct, Intelligence, and Anxiety

3

Zen and the Problem of Control

4

Beat Zen, Square Zen, and Zen

5

Spirituality and Sensuality

6

The New Alchemy

PREFACE

A LTHOUGH written at different times during the past four years, the essays here gathered together have a common point of focusthe spiritual or mystical experience and its relation to ordinary material life. Having said this, I am instantly aware that I have used the wrong words; and yet there are no satisfactory alternatives. Spiritual and mystical suggest something rarefied, otherworldly, and loftily religious, opposed to an ordinary material life which is simply practical and commonplace. The whole point of these essays is to show the fallacy of this opposition, to show that the spiritual is not to be separated from the material, nor the wonderful from the ordinary. We need, above all, to disentangle ourselves from habits of speech and thought which set the two apart, making it impossible for us to see that thisthe immediate, everyday, and present experienceis IT, the entire and ultimate point for the existence of a universe. But the recognition that the two are one comes to pass in an elusive, though relatively common, state of consciousness which has fascinated me beyond all else since I was seventeen years old.

I am neither a preacher nor a reformer, for I like to write and talk about this way of seeing things as one sings in the bathtub or splashes in the sea. There is no mission, nor intent to convert, and yet I believe that if this state of consciousness could become more universal, the pretentious nonsense which passes for the serious business of the world would dissolve in laughter. We should see at once that the high ideals for which we are killing and regimenting each other are empty and abstract substitutes for the unheeded miracles that surround usnot only in the obvious wonders of nature but also in the overwhelmingly uncanny fact of mere existence. Not for one moment do I believe that such an awakening would deprive us of energy or social concern. On the contrary, half the delight of itthough infinity has no halvesis to share it with others, and because the spiritual and the material are inseparable this means the sharing of life and things as well as insight. But the possibility of this depends entirely upon the presence of the vision which could transform us into the kind of people who can do it, not upon exhortation or appeals to our persistent, but consistently uncreative, sense of guilt. Yet it would spoil it all if we felt obliged, by that same sense, to have the vision.

For, contradictory as it may sound, it seems to me that the deepest spiritual experience can arise only in moments of a selfishness so complete that it transcends itself, by the way down and out, which is perhaps why Jesus found the companionship of publicans and sinners preferable to that of the righteous and respectable. It is a sort of first step to accept ones own selfishness without the deception of trying to wish it were otherwise, for a man who is not all of one piece is perpetually paralyzed by trying to go in two directions at once. As a Turkish proverb puts it, He who sleeps on the floor will not fall out of bed. And so, when the sinner realizes that even his repentance is sinful, he may perhaps for the first time come to himself and be whole. Spiritual awakening is the difficult process whereby the increasing realization that everything is as wrong as it can be flips suddenly into the realization that everything is as right as it can be. Or better, everything is as It as it can be.

Only two of the essays that follow have been published previously, Zen and the Problem of Control and Beat Zen, Square Zen, and Zen, the former in the first issue of Contact and the latter in The Chicago Review for the summer of 1958, and then, in expanded form, as a separate booklet by City Lights Books of San Francisco. I wish to thank the respective editors and publishers concerned for permission to include them in this volume.

Because of the rather personal and, indirectly, autobiographical nature of most of these essays, it seemed appropriate to include here a bibliography of the books and major articles which I have written to date.

San Francisco, 1960

A LAN W. W ATTS

THIS IS IT

T HE most impressive fact in mans spiritual, intellectual, and poetic experience has always been, for me, the universal prevalence of those astonishing moments of insight which Richard Bucke called cosmic consciousness. There is no really satisfactory name for this type of experience. To call it mystical is to confuse it with visions of another world, or of gods and angels. To call it spiritual or metaphysical is to suggest that it is not also extremely concrete and physical, while the term cosmic consciousness itself has the unpoetic flavor of occultist jargon. But from all historical times and cultures we have reports of this same unmistakable sensation emerging, as a rule, quite suddenly and unexpectedly and from no clearly understood cause.

To the individual thus enlightened it appears as a vivid and overwhelming certainty that the universe, precisely as it is at this moment, as a whole and in every one of its parts, is so completely right as to need no explanation or justification beyond what it simply is. Existence not only ceases to be a problem; the mind is so wonder-struck at the self-evident and self-sufficient fitness of things as they are, including what would ordinarily be thought the very worst, that it cannot find any word strong enough to express the perfection and beauty of the experience. Its clarity sometimes gives the sensation that the world has become transparent or luminous, and its simplicity the sensation that it is pervaded and ordered by a supreme intelligence. At the same time it is usual for the individual to feel that the whole world has become his own body, and that whatever he is has not only become, but always has been, what everything else is. It is not that he loses his identity to the point of feeling that he actually looks out through all other eyes, becoming literally omniscient, but rather that his individual consciousness and existence is a point of view temporarily adopted by something immeasurably greater than himself.

The central core of the experience seems to be the conviction, or insight, that the immediate now, whatever its nature, is the goal and fulfillment of all living. Surrounding and flowing from this insight is an emotional ecstasy, a sense of intense relief, freedom, and lightness, and often of almost unbearable love for the world, which is, however, secondary. Often, the pleasure of the experience is confused with the experience and the insight lost in the ecstasy, so that in trying to retain the secondary effects of the experience the individual misses its pointthat the immediate