Visit bit.ly/2cpglbO for a larger version of this map.

PREFACE

Genghis Khan, Thomas Jefferson, and God

O n an early summer night in 1787, the British historian Edward Gibbon sat in his garden house in Lausanne, where he had retreated to finish writing the last of six massive volumes on the Roman Empire, covering 170 emperors spread over 25 dynasties and 1,500 years, encompassing Europe, Africa, and Asia from the assassination of Julius Caesar on March 15 of the year 44 BC until the fall of Constantine XI to the Turks on May 29, 1453. Gibbon knew more about empires and emperors than any other scholar then or now.

Toward the end of this fifteen-year project, he showed as much interest in the future as in the past as his attention turned from the Mediterranean empires across the Atlantic Ocean to the newly formed American nation destined to become the imperial heir to Rome. Fascinated by the frequently grotesque relationship between power and religion, Gibbon closely followed the heated American debate regarding the place of religion in society, in public life, and in politics. He had been a student at Oxford, where some of these young American rebels had studied. He recognized how radical their ideals were, and how difficult it would be to give them form. Philosophers sometimes mused over the ideal of religious freedom, but no one knew how to create a society that embodied it or to implement laws to enforce religious tolerance. The Americans, led by Thomas Jefferson, were opting to offer citizens total religious freedom and a complete separation of church from state.

Gibbon had acquired his insights into the complicated relationship between power and religion through his education in continental Europe and his service as a member of Parliament. He explored the worlds religions both intellectually and spiritually, having at various points been a Catholic, a Protestant, and a Deist. In his monumental history of the Roman Empire and the foundations of Europe, he carefully charted the ebb and flow of religious currents and persecutions, and he found little to admire. After a lifetime of study, he concluded that one ruler stood above all others in matters of politics and God: Genghis Khan.

Earlier in his career, while writing the initial volumes of his history, Gibbon had shared the prejudices of his time about the Huns, Turks, and Mongols. He was repelled by their savagery and expressed a mild disdain for their leaders, including Attila the Hun and Genghis Khan, whom he called Zingis Khan. But as he grew older and matured as a scholar, he increasingly saw more to admire in the so-called barbarians than in the civilized rulers of Europe. He wrote that the Roman emperors had been filled with passions without virtues, and he denounced their lack of political and spiritual leadership. He reflected on the wanton cruelty of the Romans, who first persecuted Christians, then became Christian themselves and persecuted all others.

From his assiduous study of Western history, Gibbon came to believe that Europe offered no sound model for the establishment of religious freedom. But it is the religion of Zingis that best deserves our wonder and applause, he boldly asserted in the last volume on the Romans. Gibbon explained that in the Mongol camps different religions lived in freedom and concord. As long as they would abide by Ikh Yasa, the Great Law, Genghis Khan respected the rights of the prophets and pontiffs of the most hostile sects. By contrast, European history had often been shaped by religious fanatics who defended nonsense by cruelty and might have been confounded by the example of a Barbarian, who anticipated the lessons of philosophy, and established by his laws a system of pure theism and perfect toleration.

Few European scholars were given a chance to evaluate Gibbons comments, as his entire work was banned across much of the continent. The Catholic Church inscribed his name and book titles on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the Vaticans list of banned books, thereby making the reading or printing of his books a sin and in many countries a crime. His ideas were too radical, and his books remained on this list of forbidden books until the church finally abolished it in 1966.

In his discussion of Genghis Khans career, Gibbon inserted a small but provocative footnote, linking Genghis Khan to European philosophical ideas of tolerance and, surprisingly, to the religious freedom in the newly emerging United States. A singular conformity may be found between the religious laws of Zingis Khan and Mr. Locke, Gibbon wrote, and he cited specifically John Lockes utopian vision in the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which Locke had written in 1669 for his employer, Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper, to govern the newly acquired North American lands south of the Virginia colony.

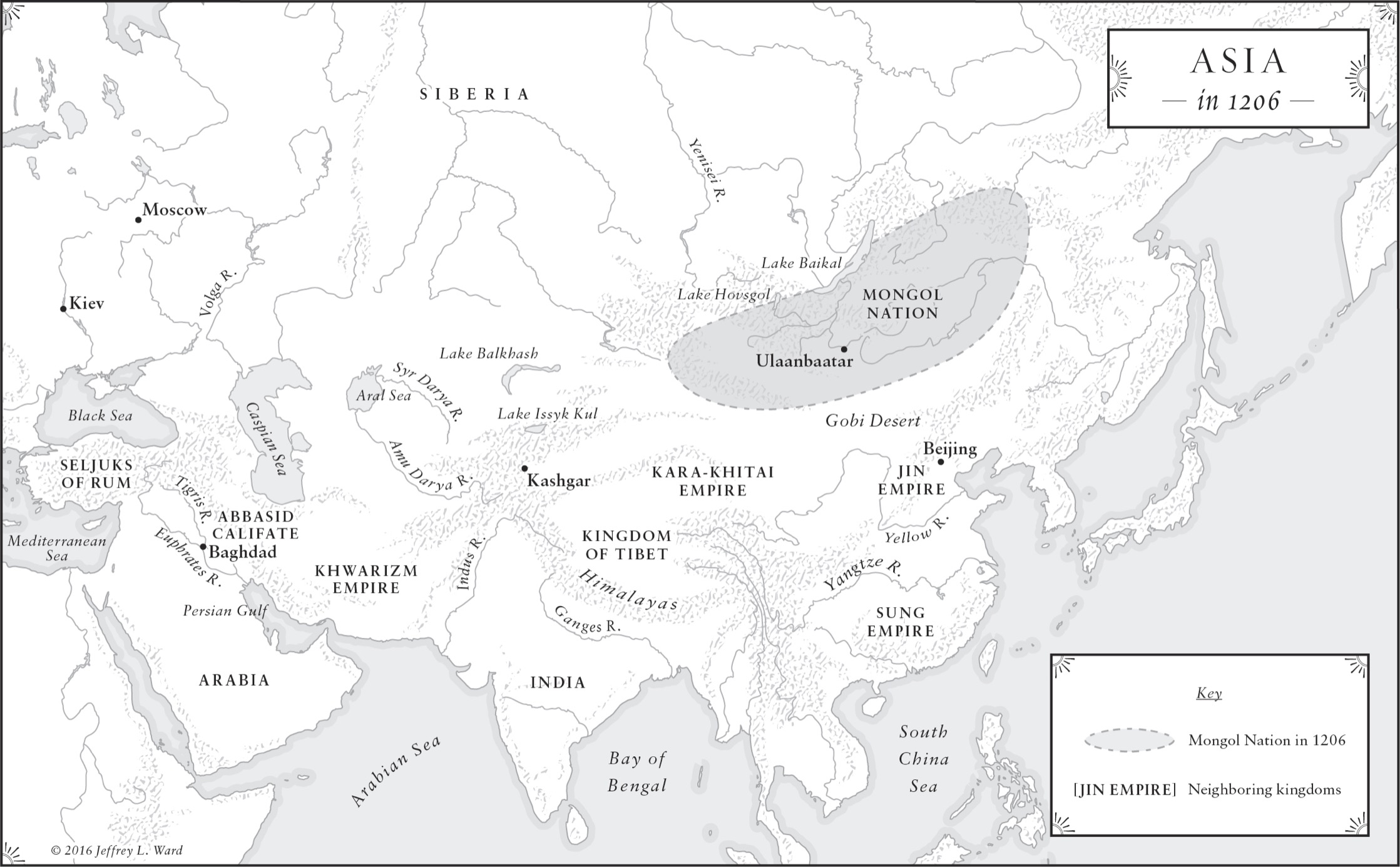

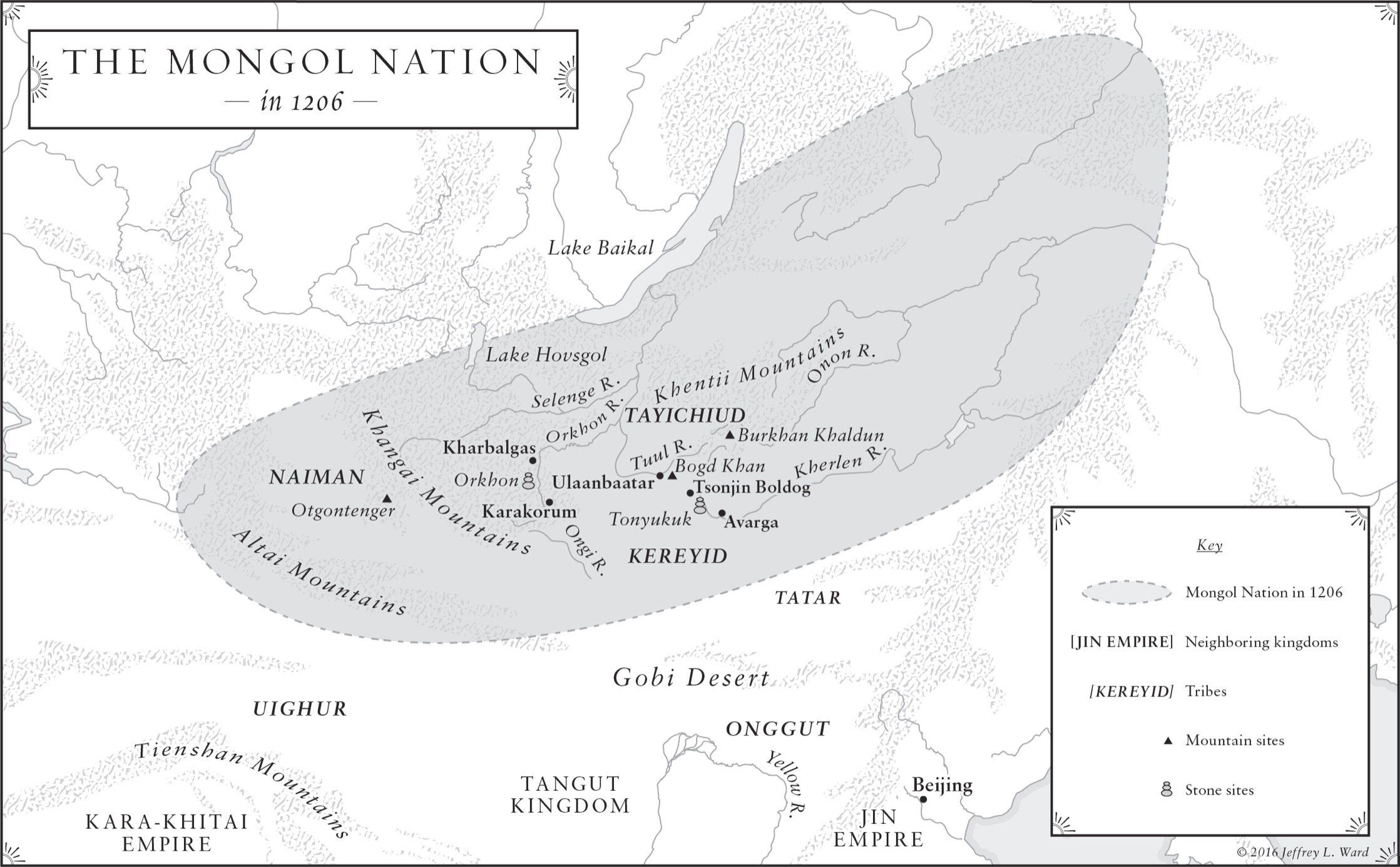

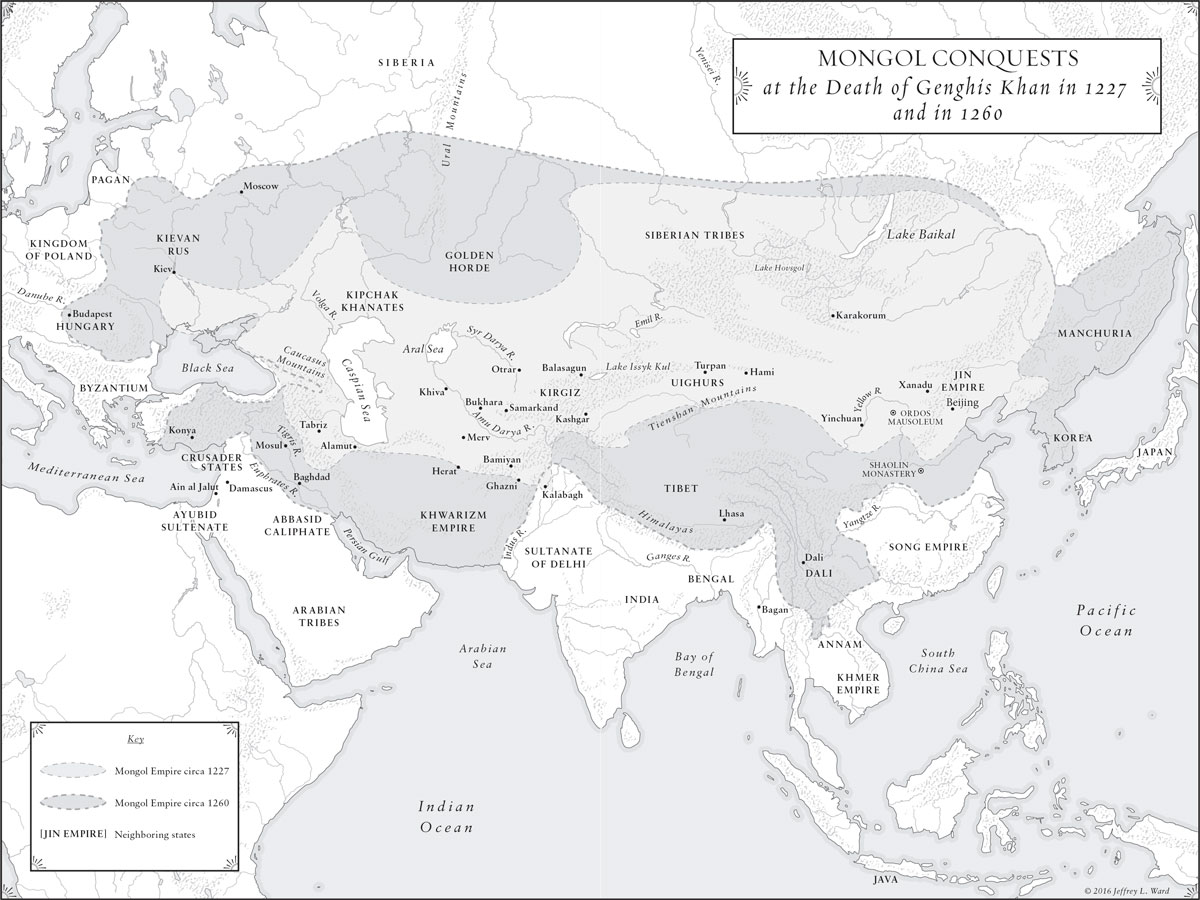

I first read Gibbons remarkable claim while writing Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, a book on the Mongol Empire. The small footnote in Gibbons work was but one of the approximately eight thousand footnotes spread throughout his one-and-a-half-million-word history, but it was the one idea that seized my attention. Gibbon was the only historian to link Genghis Khan to my homeland in South Carolina. I found the claim exciting, yet incredible. As much as I wanted to believe Gibbon, the idea seemed too farfetched even for me, an admirer of Genghis Khan and lover of all things Mongol. What possible connection could there be between the founding of the Mongol Empire in 1206 and that of the United States of America almost six hundred years later? I could find no other scholar who took the idea seriously. Nevertheless, I could not let go of this tenuous thread of connection. For my peace of mind, I decided to search for the evidence to support or refute Gibbons remark. Did the treasured Western law of religious freedom, embodied in the Constitution of the United States, originate in Asia? Was it a legacy not just of Enlightenment philosophers but also of an illiterate medieval warrior?