John Hedley Brooke - Science and Religion

Here you can read online John Hedley Brooke - Science and Religion full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Cambridge University Press, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Science and Religion

- Author:

- Publisher:Cambridge University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Science and Religion: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Science and Religion" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Science and Religion — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Science and Religion" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

FOR JANICE

My first acknowledgment is to the several generations of students at the University of Lancaster with whom I have explored the issues raised in this book, and from whom I have received unfailing stimulus. It is with great pleasure that I acknowledge a further debt to Lancaster University: to the Humanities Research Committee, which awarded a special year of study-leave to assist the completion of the text. My original research, particularly concerning the British natural theology tradition, on which parts of the discussion are based, has also been generously supported by a research grant from the Royal Society.

In keeping with the style of this series, references in the text to other secondary sources have been kept to a minimum. A bibliographic essay can make but partial amends. If I have misrepresented the sources on which I have drawn, the responsibility is of course entirely mine. To many friends and colleagues in the history of science I have a debt that is impossible to articulate fully. I am especially grateful to colleagues who have made detailed comments on earlier drafts: Professor Michael J. Crowe of the University of Notre Dame; Dr. Geoffrey Cantor of the University of Leeds; the editor of the series, Professor George Basalla of the University of Delaware; and my colleague at Lancaster, Dr. Roger Smith. Their encouragement and advice have been invaluable.

Finally, my greatest debt is to the person at whose invitation this volume was first conceived and under whose guidance (as former coeditor of the series) it assumed its present shape: the late William Coleman of the University of Wisconsin. Many have rightly said that his untimely death deprived the history of science of one of its true masters. The many respects in which this book is the better for his recommendations constitute a further tribute which, had he lived to see it, would not, I hope, have been unwelcome.

In a classic discussion of the origins of modern science, the historian Herbert Butterfield drew a much-quoted parallel. Such was the impact of the seventeenth-century Scientific Revolution that the only landmark with which it could be compared was the rise of Christianity. In shaping the values of Western societies, science and the Christian religion had each played a preeminent part and made a lasting impression. Exaggerated or not, such comparisons raise an obvious question. What was the relationship between these powerful cultural forces? Were they complementary in their effects, or were they antagonistic? Did religious movements assist the emergence of the scientific movement, or was there a power struggle from the start? Were scientific and religious beliefs constantly at variance, or were they perhaps more commonly integrated, both by clergy and by practicing men of science? How has the relationship changed over time?

Such questions are easier to formulate than to answer. Since the seventeenth century every generation has taken a view on their importance without, however, reaching any consensus as to how they should be answered. Writing some sixty years ago, the philosopher A. N. Whitehead considered that the future course of history would depend on the decision of his generation as to the proper relations between science and religion so powerful were the religious symbols through which men and women conferred meaning on their lives, and so powerful the scientific models through which they could manipulate their environment. Because every generation has reappraised the issues, if not always with the same sense of urgency, there has been no shortage of opinion as to what that proper relationship should be.

In popular literature three positions are commonly found, which, though not equally unsatisfactory, turn out to be problematic. One often encounters the view that there is an underlying conflict between scientific and religious mentalities, the one dealing in testable facts, the other deserting reason for faith; the one relishing change as scientific understanding advances, the other finding solace in eternal verities. Where such a view holds sway, it is assumed that historical analysis provides supporting evidence of territorial squabbles in which cosmologies constructed in the name of religion have been forced into retreat by more sophisticated theories coming from science. The nineteenth-century scholars J. W. Draper and A. D. White constructed catalogs of this kind, in which scientific explanations repeatedly challenged religious sensibilities, in which ecclesiastics invariably protested at the presumption, and in which the scientists would have the last laugh.

Typical was Whites account of the reluctance of the clergy to fix lightning rods to their churches. In 1745 the bell tower of St. Marks in Venice had once again been shattered in a storm. Within ten years, Benjamin Franklin had mastered the electrical nature of lightning. His conducting rod could have saved many a church from that divine voice of rebuke, which thunder had often been supposed to be. But White reported that such meddling with providence, such presumption in controlling the artillery of heaven, was opposed so long by clerical authorities that the tower of St. Marks was smitten again in 1761 and 1762. Not until 1766 was the conductor fixed after which the monument was spared. Whites picture of religious scruples and shattered towers symbolizes the popular notion of an intrinsic and perennial conflict. An ounce of scientific knowledge could be more effective in controlling the forces of nature than any amount of supplication.

Figure Int.1. Francesco Guardi (171293), Venice Piazza San Marco . Dating from c. 1760, this painting shows St. Marks Cathedral and its bell tower. Reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees, The National Gallery, London.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

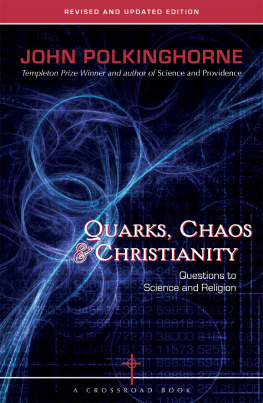

Similar books «Science and Religion»

Look at similar books to Science and Religion. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Science and Religion and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.