Chod Practice in the Bon Tradition

FORT WORD BY "I'ENZIN WANGYAL BINI'OCIIE'

CHOD PRACTICE IN THE BON TRADITION

Chod Practice in the Bon Tradition

Tracing the origins of chod (gcod) in the Bon tradition, a dialogic approach cutting through sectarian boundaries

Alejandro ChaoulForewords by Yongdzin Lopon Tenzin Namdak and Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche

If you feel like going to a cemetery, fine, but this is not necessary. A cemetery is a place where corpses and frightening and repulsive things are found. Milarepa said that we permanently have a corpse at our disposal, it is our body! There is even another cemetery, the greatest of all cemeteries, it is the place where all our thoughts and emotions come to die.- Kalu Rinpoche, Secret Buddhism: Vajraydna PracticesIn memory of my first personal teacher, Ven. Yeshe Dorje Rinpoche,In gratitude to my parents, Susi Reich, and Fred Chaoul,andWith unbounded love for my family: Erika, Matias & Karina

Table of Contents

xi

xiii

xv

xvii

Foreword by

Yongdzin Lopon Tenzin Namdak

N THE BON TRADITION, all practices, regardless of whether they pertain to Sutra, Tantra, or Dzogchen, lead one towards the path of liberation. Chod, however, is a special method with particular characteristics for this. Although Chod is common to both Tibetan Bon and Buddhist schools, the original basis of this practice in the two traditions is quite different. The Chod practice according to Buddhist tradition is said to be originally based on the Prajnaparamita while that of Tibetan Bon rests upon Tantric practices. However, in both traditions the Chod practice is performed in a manner which has more in common with Tantra than Sutra, and in both traditions it is known as a very effective and powerful practice bringing the practitioner a strong experience of profound generosity as well as liberation from self-grasping, the root of Samsara. It is, then, a forceful tool for developing one's practice and as such, makes up one of the Four Generosities of the Bon tradition which are practiced on a daily basis.

N THE BON TRADITION, all practices, regardless of whether they pertain to Sutra, Tantra, or Dzogchen, lead one towards the path of liberation. Chod, however, is a special method with particular characteristics for this. Although Chod is common to both Tibetan Bon and Buddhist schools, the original basis of this practice in the two traditions is quite different. The Chod practice according to Buddhist tradition is said to be originally based on the Prajnaparamita while that of Tibetan Bon rests upon Tantric practices. However, in both traditions the Chod practice is performed in a manner which has more in common with Tantra than Sutra, and in both traditions it is known as a very effective and powerful practice bringing the practitioner a strong experience of profound generosity as well as liberation from self-grasping, the root of Samsara. It is, then, a forceful tool for developing one's practice and as such, makes up one of the Four Generosities of the Bon tradition which are practiced on a daily basis.

This book, The Cho'd Practice in the Bo'n Tradition, is a first of its kind, attempting a comparison between the Chod practices of Bon and the Buddhist traditions. Alejandro Chaoul is a long-term student of both academic and spiritual ways, and his thorough examination of both original as well as scholarly sources relating to this practice in Tibetan and in English has resulted in this book. I therefore convey my congratulations to the author for his inspired work and hope this book will be of great benefit for scholars and practitioners alike to widen and enhance their knowledge about this method of practice.

Yongdzin Lopon Tenzin NamdakTriten Norbutse MonasteryKathmanduDecember 17, 2007

Foreword by

Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche

LEJAND RO CHAOUL has been my student for more than fifteen years. Over the years I have known him, he has fully engaged in Bon study and practice, both academically and experientially, and has played an important role in establishing the international activities of Ligmincha Institute through teaching, creating support materials for practice and study, and otherwise offering his dedicated assistance. Besides working with me in his research into the chod practice, he conducted part of these studies at Tritan Norbutse Monastery in Nepal in close collaboration with my beloved teacher Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche. For all these reasons Chaoul has the ideal level of knowledge and experience necessary for creating this in-depth yet accessible presentation of chod.

LEJAND RO CHAOUL has been my student for more than fifteen years. Over the years I have known him, he has fully engaged in Bon study and practice, both academically and experientially, and has played an important role in establishing the international activities of Ligmincha Institute through teaching, creating support materials for practice and study, and otherwise offering his dedicated assistance. Besides working with me in his research into the chod practice, he conducted part of these studies at Tritan Norbutse Monastery in Nepal in close collaboration with my beloved teacher Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche. For all these reasons Chaoul has the ideal level of knowledge and experience necessary for creating this in-depth yet accessible presentation of chod.

The chod practice of Bon is very much rooted in many of the teachings of the Bon tradition, such as the Mother Tantra (Ma Gyii), as Chaoul rightly points out. Chod continues to be widely practiced in the East, and since its recent introduction to the West, it has been met with much enthusiasm by Western students in the Bon Buddhist communities.

Chaoul's book offers a comprehensive intellectual understanding of chod and its origins within both the Bon and Buddhist traditions, and as such will have great benefit for scholars as well as for those who wish to engage in chod as a daily ritual or meditation practice.

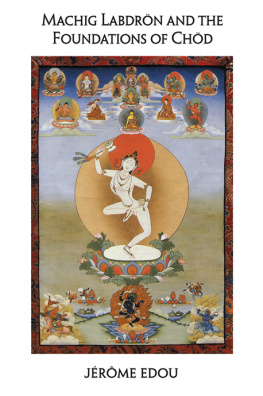

As Chaoul concludes, the similarities between the Bon and Buddhist forms of the practice are more valid than their differences. The core purpose of chod is to turn fear into a path to liberation. The practitioner actively seeks out fearful experiences, using fear as an opportunity to visualize cutting apart one's own physical body, symbolizing the cutting of the ego, and thus cultivating wisdom. The practitioner further visualizes transforming the body into an offering that satisfies all beings, thus cultivating generosity and detachment.

Through this ancient and profound practice, anyone who is able to recognize their own fear - whether its source is external or internal - can face that fear, challenge it, and overcome it. Ultimately, fear becomes a tool to cultivate enlightened qualities. Anyone who understands these principles of the chod practice will be benefited, and this book offers an excellent contribution to this understanding.

- Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche

Acknowledgments

HE LACK OF INFORMATION on the Bon tradition of chod (gcod), inspiration from Ven. Yeshe Dorje Rinpoche and Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche concerning the topic and practice of chod, and my particular deep interest in the Bon tradition as a whole led me to explore chod and its origins in the Bon tradition. In this enterprise the help provided by Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche' and Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche has been invaluable to the point that no words in either English or Tibetan suffice to express my most sincere thanks and thugje the (thugs rje che).

HE LACK OF INFORMATION on the Bon tradition of chod (gcod), inspiration from Ven. Yeshe Dorje Rinpoche and Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche concerning the topic and practice of chod, and my particular deep interest in the Bon tradition as a whole led me to explore chod and its origins in the Bon tradition. In this enterprise the help provided by Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche' and Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche has been invaluable to the point that no words in either English or Tibetan suffice to express my most sincere thanks and thugje the (thugs rje che).

This book stems from my MA thesis at the University of Virginia. I would like to thank my advisors, David Germano and Karen Lang, for their suggestions and encouragement, and in particular, David Germano, whose commitment to excellence and continuous support are a great source of inspiration. Thanks also are due to the Rocky Foundation for awarding me a Buddhist Fellowship that allowed me to visit Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak in Nepal, whose help, as I mentioned, was invaluable for this project.

Next page

N THE BON TRADITION, all practices, regardless of whether they pertain to Sutra, Tantra, or Dzogchen, lead one towards the path of liberation. Chod, however, is a special method with particular characteristics for this. Although Chod is common to both Tibetan Bon and Buddhist schools, the original basis of this practice in the two traditions is quite different. The Chod practice according to Buddhist tradition is said to be originally based on the Prajnaparamita while that of Tibetan Bon rests upon Tantric practices. However, in both traditions the Chod practice is performed in a manner which has more in common with Tantra than Sutra, and in both traditions it is known as a very effective and powerful practice bringing the practitioner a strong experience of profound generosity as well as liberation from self-grasping, the root of Samsara. It is, then, a forceful tool for developing one's practice and as such, makes up one of the Four Generosities of the Bon tradition which are practiced on a daily basis.

N THE BON TRADITION, all practices, regardless of whether they pertain to Sutra, Tantra, or Dzogchen, lead one towards the path of liberation. Chod, however, is a special method with particular characteristics for this. Although Chod is common to both Tibetan Bon and Buddhist schools, the original basis of this practice in the two traditions is quite different. The Chod practice according to Buddhist tradition is said to be originally based on the Prajnaparamita while that of Tibetan Bon rests upon Tantric practices. However, in both traditions the Chod practice is performed in a manner which has more in common with Tantra than Sutra, and in both traditions it is known as a very effective and powerful practice bringing the practitioner a strong experience of profound generosity as well as liberation from self-grasping, the root of Samsara. It is, then, a forceful tool for developing one's practice and as such, makes up one of the Four Generosities of the Bon tradition which are practiced on a daily basis. LEJAND RO CHAOUL has been my student for more than fifteen years. Over the years I have known him, he has fully engaged in Bon study and practice, both academically and experientially, and has played an important role in establishing the international activities of Ligmincha Institute through teaching, creating support materials for practice and study, and otherwise offering his dedicated assistance. Besides working with me in his research into the chod practice, he conducted part of these studies at Tritan Norbutse Monastery in Nepal in close collaboration with my beloved teacher Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche. For all these reasons Chaoul has the ideal level of knowledge and experience necessary for creating this in-depth yet accessible presentation of chod.

LEJAND RO CHAOUL has been my student for more than fifteen years. Over the years I have known him, he has fully engaged in Bon study and practice, both academically and experientially, and has played an important role in establishing the international activities of Ligmincha Institute through teaching, creating support materials for practice and study, and otherwise offering his dedicated assistance. Besides working with me in his research into the chod practice, he conducted part of these studies at Tritan Norbutse Monastery in Nepal in close collaboration with my beloved teacher Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche. For all these reasons Chaoul has the ideal level of knowledge and experience necessary for creating this in-depth yet accessible presentation of chod. HE LACK OF INFORMATION on the Bon tradition of chod (gcod), inspiration from Ven. Yeshe Dorje Rinpoche and Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche concerning the topic and practice of chod, and my particular deep interest in the Bon tradition as a whole led me to explore chod and its origins in the Bon tradition. In this enterprise the help provided by Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche' and Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche has been invaluable to the point that no words in either English or Tibetan suffice to express my most sincere thanks and thugje the (thugs rje che).

HE LACK OF INFORMATION on the Bon tradition of chod (gcod), inspiration from Ven. Yeshe Dorje Rinpoche and Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche concerning the topic and practice of chod, and my particular deep interest in the Bon tradition as a whole led me to explore chod and its origins in the Bon tradition. In this enterprise the help provided by Yongdzin Tenzin Namdak Rinpoche' and Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche has been invaluable to the point that no words in either English or Tibetan suffice to express my most sincere thanks and thugje the (thugs rje che).