T HE ANGELS

BY

Dom Anscar Vonier, O.S.B.

Abbot of Buckfast

Assumption Press

2013

Nihil Obstat

Innocentius Apap, O.P.., S.Th.M.

Censor Deputatus.

Imprimatur

Edm. Can. Surmont

Vicarius Generalis

Jan 3, 1928

The Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the Nihil Obstat and the Imprimatur agree with the content, opinions or statements expressed.

This book was originally published in 1928 by The Macmillan Company.

Copyright 2013 Assumption Press.

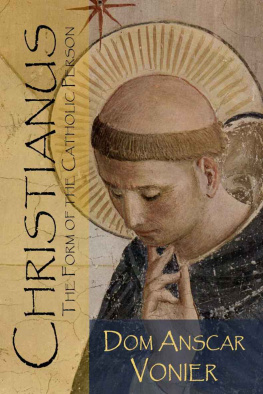

Cover image: Angels in Adoration, Detail, by Benozzo Gozzoli, c. 1460 .

Contents

I

Traditional Angelic Nature

There is in every treatment of Catholic thought, unless it be a rigidly technical treatise, that happy mixture of the certain, the extremely probable, and the moderately probable which constitutes a real philosophy, where conservatism and liberalism are congenially blended. Thus in the pages which follow all the things written down are not matters of faith, nor would it be possible in a small volume of this kind to affix a proper theological note to every proposition, distinguishing what is strictly of faith from the conclusions and happy inspirations of minds fond of the things of God; but much edification and instruction can be derived from the sayings of theologians and preachers which are not de fide (of the faith), but rather the legitimate speculations of minds habitually attuned to revealed truth.

Our first authority on the history of the angels, their lives and their natures, is found in Holy Scripture. There is a great oneness in the presentment of angelic character in the various books of the Bible, from Genesis to Apocalypse; the angelic type never alters, we may even venture to say that it never develops as the divine revelation in other matters goes on and gains momentum from century to century; what the angels do at Bethel they do also in the days of Christ, they ascend and descend upon the Son of man (John 1:51). Cherubim with a flaming sword, turning every way, to keep the way of the tree of life (Gen 3:24) are visions as formidable as any angelophany in Ezechiel or the Apocalypse.

There is not, therefore, in our angelology that progressive revelation of a mystery which is the characteristic of our Christology; the mystery of the God-Man is revealed gradually to the minds of men; not so that of the angels; they are made completely manifest from the very beginning, and though, in the course of the centuries of the faith, angels show forth now one kind of activity now another, their essential behavior is always the same.

The fact is that our Scriptures never teach us anything about the spirits of the invisible world ex professo (expressly), they never narrate anything about them as a revelation of their mysterious existence; the inspired writers take them for granted and mention them only in connection with human history, the history of the people of God, and the history of Christ. Nothing is more casual and unexpected than the mention of angels in every portion of the Scriptures; you never know when to expect an angel; there is no set of events of which you could predict with certainty that they would bring an angel from heaven to earth. The same thing which at one moment is done through angelic ministry, at another time is left in its natural setting.

Our Scriptures, then, may be said to accept the angelic world as a complete, self-sufficient, unaccountable power, which cannot itself be altered by the course of human events, but which may influence them whenever it pleases. Nor do the Scriptures distinguish clearly at all times between angelic intervention and divine intervention; the heavenly visitant who is called angel passes at once into a role which is obviously divine. This is very remarkable in the oldest angelophany in the Bible the angel whom we might call the angel of the family of Abraham; the heavenly messenger who spoke to Hagar, the slave-wife of Abraham, is at the same time angel and Lord of life:

And the angel of the Lord having found her (Hagar), by a fountain of water in the wilderness, which is in the way to Sur in the desert, He said to her: Hagar, handmaid of Sarai, whence comest thou? And whither goest thou? And she answered: I flee from the face of Sarai, my mistress. And the angel of the Lord said to her: Return to thy mistress, and humble thyself under her hand. And again he said: I will multiply thy seed exceedingly, and it shall not be numbered for multitude (Gen 16:7-10).

The clearest instance in Genesis of angelic, as distinct from divine manifestation is perhaps the vision of Jacob:

And he saw in his sleep a ladder standing upon the earth, and the top thereof touching heaven: the angels also of God ascending and descending by it; And the Lord, leaning upon the ladder, saying to him: I am the Lord God of Abraham thy father, and the God of Isaac. The land, wherein thou sleepest, I will give to thee and to thy seed (Gen 28:12-13).

There is no mention of angels in the great period before the flood, nor are they described as ministering to Noah in his peril; the angelic ministry, as a ministry, begins with the history of the Jewish people. In the narrative of creation there is not the remotest mention of them, and that the evil spirit should be spoken of long before any other power of the unseen world shows clearly that the inspired writers never gave themselves any other task than the history of man and his vicissitudes. Spirits are not the theme of the Bible.

One might not unaptly compare the attitude of our Scriptures towards the spirits with their attitude towards those portions of the human race which are neither the Jewish nation itself nor the Christian Church. The peoples who are not the chosen race come frequently into contact with it, and are even meant to help the people of God in many ways; the scriptural allusions to them are therefore very valuable from the historical point of view, and we learn a good deal about the non-Jewish peoples from the Bible, though that book is in no sense a history of mankind at large.

In a similar way the inspired historians and writers, whilst dealing with mans supernatural career on earth, have revealed to us much of the unseen world, but only incidentally, and in so far as it concerns mans eternal welfare. We must bear in mind this relative position of our angelology in the Scriptures, and not expect more than fragments of angelic history; yet those fragments are precious and instructive in the extreme.

It would not serve the purpose of this book to quote and explain all the various scriptural allusions to the spirits; every reader can perform this task for himself. Broadly speaking, we may divide the references of Holy Writ to the angels into four classes the historical , the liturgical , the theological , and the prophetic .

By historical angelophany I mean all those assertions found in the Bible that spirits did a work, bore a message, or lent their help to humanity from the time of Hagar to that of Peter in his prison. These activities are narrated as ordinary historical events, and they are never concerned with angels in their multitudes, but only with them as individual spirits.

Then there are the liturgical allusions to angelic presence in divine worship; the psalms abound in them, and the sweet singer of Israel professes to utter Gods praises in the presence of the angels. The multitude of the heavenly army praising God (Luke 2:13) at Christs nativity may be considered under this heading.

As theological references those passages of the Scriptures may be quoted where the heavenly spirits are mentioned, not in connection with worship or missions, but as a portion of the supernatural world; as when Christ is said by St. Paul to be raised up on Gods right hand in heavenly places above all principality and power and virtue and dominion (Eph 1:20-21), when the same Apostle says that the Christian man has come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to the company of many thousands of angels (Heb 12:22), or when Christ himself says that he will confess the name of his faithful witness before the angels of God (Rev 3:5), or that there is joy before the angels of God upon one sinner doing penance (Luke 5:10). The office of the guardian angels may also be considered as belonging to the theological aspect of angelology; the Scriptures reveal to us a side of the spiritual world which is more than a transient mission, in our Lords words:

Next page