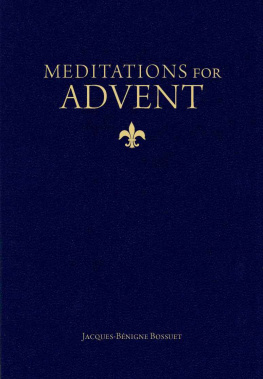

Jacques-Bnigne Bossuet

Meditations for Advent

Translated by Christopher O. Blum

SOPHIA INSTITUTE PRESS

Manchester, New Hampshire

Meditations for Advent is a translation of lvations Dieu sur tous les mystres de la religion chrtienne, from Oeuvres compltes de Bossuet, edited by Abb Guillaume and published by Briday in Lyon, France, in 1879.

Copyright 2012 Christopher Blum

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved

Cover design by Carolyn McKinney

Scriptural quotations in this book are taken from the Catholic Edition of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1965, 1966 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Sophia Institute Press

Box 5284, Manchester, NH 03108

1-800-888-9344

www.SophiaInstitute.com

Sophia Institute Press is a registered trademark of Sophia Institute.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bossuet, Jacques Bnigne, 1627-1704.

[lvations Dieu sur tous les mystres de

la religion chrtienne. English.Selections]

Meditations for Advent / Jacques-Bnigne Bossuet ;

translated by Christopher O. Blum.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-933184-87-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

978-1-622821-14-3 (eBook) 1. Meditations.

I. Blum, Christopher Olaf, 1969- II. Title.

BX2183.B6313 2012

.332 dc23

2012031204

Contents

Foreword

Every year our holy mother the Church invites us to make our way back to Bethlehem. And when we arrive, what is it that we see there? Nothing but three poor people who love one another, as the poet Claudel said, but three poor people who will change the face of the earth.

There is great wisdom in the Churchs setting aside as holy that month of expectation that is the liturgical season of Advent. For, like the Holy Family, we too are poor. Yet we are poor in the very way that they were rich, and rich in the way that they were poor. And this is why we sorely need Advent as an annual occasion to listen to the prophet Isaiah, to marvel at the Annunciation, the Visitation, and the birth of Saint John the Baptist, to enter more deeply into the meaning of those two great songs of faith that frame the Churchs daily prayer, the Benedictus and the Magnificat , and to join Saint Joseph and the Blessed Virgin in silent adoration of the incarnate Son of God. For just such an Advent journey of contemplation, this slim volume is an admirable vade mecum . In it you will find a distillation of the doctrine and the piety of an eloquent preacher and a man of deep and weighty prayer.

The days are not so long ago when the figure of Jacques-Bnigne Bossuet (1627-1704) needed no introduction and when the very thought of translating his sublime French into English would have been considered an impertinence. But we no longer live in the world of Monsignor Knox and Mr. Waugh and certainly not that of Mr. Belloc a world in which it could be taken for granted that educated men and women read French and that educated Catholics read the right sort of French authors. And so there is another task of ressourcement that must be undertaken, a reclaiming of an inheritance, one of whose central figures is the Eagle of Meaux, as the great Bossuet was called, after the name of his bishopric and for his clear vision and elevated style.

Born to an industrious and dignified Burgundian family, Bossuet labored mightily in the vineyard of the Word, as a preacher should. He knew the Scriptures by heart. He read and reread the Fathers, chiefly Saint Augustine. He made his own the doctrine of the Church, especially as transmitted by Saint Thomas Aquinas. With his inimitable craft, he put this solid learning to work, producing monuments of French style such as the funeral orations for the princess Henriette-Marie and the great Cond and becoming the schoolmaster not only of the dauphin, son of the Roi Soleil , but of generations of Catholics in la belle France and wherever the French tongue was read. His Discourse on Universal History and History of the Variations of the Protestant Churches cast a long shadow, shaping minds as varied as Joseph de Maistre and T. S. Eliot, Christopher Dawson, and Paul Claudel.

The work here at hand is a careful selection of forty daily meditations sufficient to stretch from Thanksgiving into the Octave of Christmas taken from a much longer work, the lvations Dieu sur tous les mystres de la religion chrtienne . The first word of this title defeats easy translation, although its meaning is plain enough. These are texts meant to assist the Christian in the difficult task of lifting the mind to the consideration of God. The notion here is one common to the French School of spirituality that descends from Pierre de Brulle: that the omnipotent and eternal God is not like us, but because of his infinite condescension in becoming man, we are apt to think that he is. And so, as an astute commentator on Bossuet has said, these meditations spring in part from the authors conviction that the majority of our errors in the Christian life and particularly in the life of devotion arise from our failure sufficiently to respect God, from our failure to esteem him highly enough. It is Bossuets lofty sense of Gods grandeur that gives us the sonorous meditations on the Creation, on the Word, and on the priesthood of Jesus Christ. Yet the same Bossuet who was heir to the austere theological vision of Cardinal de Brulle was equally the follower of the mild Saint Francis de Sales and the charitable Saint Vincent de Paul. So here too we find stirring calls to poverty, silence, and simplicity of life within the context of reflections on the Blessed Virgin and in one of the earliest and most celebrated examples of its kind a sermon in appreciation of the holy patriarch Saint Joseph.

The Father, as we are told by the Incarnate Word himself, seeks souls who will adore him in spirit and in truth (John 4:23). There is work enough here for both heart and mind, and these gleanings from Bossuets harvest of the French School of spirituality are trustworthy help for the task.

Romanus Cessario, O.P.

Paul Claudel, Toi, qui es-tu? (Paris: Gallimard, 1936), 54. Jean Calvet, La littrature religieuse de Franois de Sales Fnelon (Paris: Del Duca, 1956), 314-315.

Prayer to Jesus Christ

Jesus, my Savior, true God and true man, and the true Christ promised to the patriarchs and the prophets from the beginning of the world and, in time, faithfully bestowed to the holy people you had chosen, you have said by your holy and divine mouth: This is eternal life, that they know thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom thou hast sent (John 17:3). Believing in these words, and with the help of your grace, I wish to be attentive to the task of knowing God and knowing you.

So do I draw as near to you as I can, with a lively faith, to know God in you and by you, and to know him in a manner worthy of God that is, in a manner that leads me to love and to obey him, in accord with the words of your beloved disciple: He who says I know him but disobeys his commandments is a liar (1 John 2:4), as well as your very own: He who has my commandments and keeps them, he it is who loves me (John 14:21).

To know you well, O my God and dear Savior, I wish always, with the help of your grace, to contemplate you in all that befalls you and in all of your mysteries, and at the same time to know your Father, who gave you to us, and the Holy Spirit that you both have sent to us. So do I wish to love you with true faith, a faith working through love (Gal. 5:6). Amen.

Next page