Lew Welch - How I Read Gertrude Stein

Here you can read online Lew Welch - How I Read Gertrude Stein full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

How I Read Gertrude Stein: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How I Read Gertrude Stein" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

How I Read Gertrude Stein — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How I Read Gertrude Stein" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Strangeness always goes off very quickly ... but then the pleasure of looking if you like to look is always a pleasure." (Eh. 174)

Gertrude Steins use of language has caused much merriment among reviewers and critics, but has achieved its intended purpose, as she notices in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas: My sentences do get under their skin .. (ABTl 0) This is, I suppose, one of the aims of every writer, but Stein has a rather special reason for wishing her readers to be conscious of the verbal level of her writing.

Much of her writing is, in a way significantly different from other literature, a demonstration of an abstraction (generalization) which has been derived from her analysis of literature, and she often uses the methods of literature to make the same points which critics make by means of expositionary writing. It is convenient, therefore, to begin with the critics discussion of language, before investigating Steins demonstration of the same point.

It is fairly easy to distinguish between the language of science and the language of literature. The mere contrast between thought and emotion or feeling is, however, not sufficient. Literature does contain thought, while emotional language is by no means confined to literature ... the ideal scientific language is purely denotative: it aims at a one-to-one correspondence between sign and referent. The sign is completely arbitrary, hence can be replaced by equivalent signs. The sign is also transparent; that is, without drawing attention to itself, it directs us unequivocally to its referent.

... whatever the mixed modes apparent upon an examination of concrete literary works of art, the distinction between the literary use and the scientific use seems clear: literary language is far more deeply involved in the historical structure of the language; it stresses the awareness of the sign itself.... (Wellek and Warren, 12, 13)

This distinction is useful although, like any generalization about literature, it becomes difficult to apply at times. It is, for instance, not easy to maintain that the words of W. C. Williams, Wallace Stevens, or other imagist poets draw attention to themselves as signs. But like most generalizations, it is useful insofar as it gives us a way to discuss a phenomenon that undoubtedly contributes to our enjoyment of many, perhaps most, specific poems and individual poets.

It is certainly sensible to suppose that the writer of literature is more acutely aware of language than are most of his readers, whether he wishes his finished work of art to draw attention to its signs, or to the images to which those signs refer. Gertrude Stein has taken this position but instead of making the above kind of statement, has written a book entitled How to Write in which she attempts to force one into an acute awareness of sign.l She does not teach one how to write, but attempts to give one an experience with language that will enable one to write.

She does this by a treatise on language, sentence structure, and grammar which is presented almost exclusively by means of example. She includes only enough exposition to assure one that her point is the teaching of the elements of English, and uses the title to show the reader that her lesson and the way in which it is being taught has to do with the writing of literature. Her statements of exposition usually look like this: here is a sentence or think in articles or successions of words are so agreeable it is about this. But perhaps her most explicit statement is: It is impossible to avoid meaning and if there is meaning and it says what it does there is grammar. (HTW 71)

But how is it possible for meaning to do with the result that there is grammar? An example is this sentence: Grammar makes her name trout and love birds. It is possible to read the sentence to mean that her name is trout, but if one does this the phrase and love birds demands that one consciously change name from a noun to a verb. This sentence does not always elicit this response; I have tested it upon several people, about half of whom responded in the above way, and half just stared. The following sentence usually succeeds in making one conscious of syntax: A seated pigeon turned makes sculpture.

She uses many such tricks with words, always to the end of making one conscious of the fact that the reader is enforcing the syntax upon each sentence, that syntax is not the obvious and passive thing that one had perhaps supposed.

To get back to the distinction between sign and referent by giving an example of the way in which she forces one to be conscious that words are signs:

And and they will go.

A is an article.

They are usable. They are found and able and edible. And so they are predetermined and trimmed.

The which is an article.

With them they have that. What which, they have the point in which it is close to the purpose.

Think in articles.

The the inclusion.

The in inclusion.

A fine finely in in fanning.

A is an advice.

A is an advice.

If a is an advice an is a temporal wedding. ,,

If a is an advice an is an is in an and temptation ridden.

Temptation redden.

If a is an advice an is a temptation ridden. ( HTW 129)

It is interesting to notice that she makes one aware of the sign and by making it into a noun. Perhaps being conscious of and is not very important, but it seems to me that she had to do it this way because of all parts of speech articles and conjunctions have the least obvious referent, and at the same time are very rarely noticed as signs.2 It is, for example, very difficult to think of pigeon as a sign, for one always tends to see the bird. But once having been made aware of articles in the above way, the step to thinking in a like manner of all words is a short one.

It is also interesting to notice that although of course articles are not predetermined and trimmed, by saying this she turns predetermined and trimmed into signs and at the same time one is entertained. The entertainment value of such verbal playfulness is extremely important in a work such as this, for unending examples of sentences could easily become terribly tedious.

I have tried it on many of my acquaintances, merely by giving them the book without comment, and have noticed that they usually become quickly absorbed and find it necessary to read aloud sentences such as these from the first pages: Painting now after its great moment must come back to be a minor art and When a dog is no longer a lap dog there is a temporary inattention. The first of these sentences, and perhaps the second as well, may have seemed interesting because of their content, but I hardly think that this is true of a sentence from the third page, which was read aloud to me by all of those who continued reading this far: Apart disposed deposed that he went. This too was popular: It was joined and generally resembled when it is and belongs to all which they rent. We might compare a passage from a systematic presentation of this subject with a passage from How to Write, judging the two both for their ability to hold ones attention, and for their ability to make their point. I quote from English Grammar, selected and prepared by the editorial staff, United States Armed Forces Institute, page 47 not a definitive work, but one which attempts to be very simple and very clear.

He hit the ball.

Hit is the verb, and he is the subject. But he hit by itself doesnt make a complete statement. You ask right away, What did he hit? The word that answers that question is ball. Ball, which receives the action of the verb, is called the object of the verb. The receiver of the action is the object of the verb.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

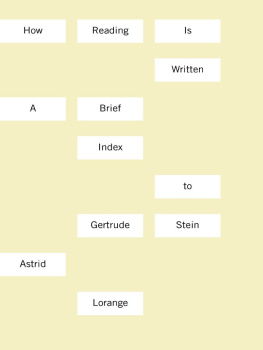

Similar books «How I Read Gertrude Stein»

Look at similar books to How I Read Gertrude Stein. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How I Read Gertrude Stein and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.