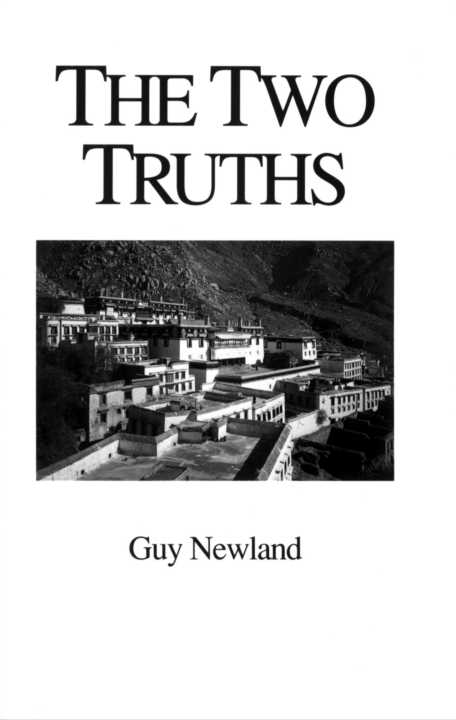

Guy Newland - The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism)

Here you can read online Guy Newland - The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1992, publisher: Snow Lion Publications, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism)

- Author:

- Publisher:Snow Lion Publications

- Genre:

- Year:1992

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Guy Newland: author's other books

Who wrote The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism)? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book has been approved for inclusion in Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. The editorial board for this series includes:

Roger Jackson

Carleton College

Anne Klein

Rice University

Karen Lang

University of Virginia

John Strong

Bates College

by Guy Newland

vii

Except in the bibliography, transliterated words are underlined and (unless the foreign word itself is under discussion) set off by parentheses. The transliteration of Tibetan words into roman letters follows the system set out by Turrell Wylie, with the modification that no letters are capitalized.' Transliteration of Sanskrit words follows standard practice. A few words (e.g., "Bodhisattva," "Buddha," "karma," "tantra," and "yogi") of Sanskrit origin are treated as English words.

When not marked as transliterations, Tibetan proper nouns are presented according to a modified version of a phoneticization system devised by Jeffrey Hopkins? In the following table, the transliterated Tibetan root letters appear on the left and their phonetic equivalents on the right.

The macron above a consonant indicates a "high" tone, the pronunciation of which Hopkins describes as "not deep in the throat, but higher or more forward and tending to be sharp and short."' Nasals in the root position take on this high tone only when affected by a prefixed or superscribed letter. In order to better reflect actual pronunciation (Lhasa dialect), this system substitutes k and p for Wylie's g and b, as in the name Dak-tsang (stag tshang). A subjoined la causes a syllable to be pronounced "la," except in the case of zla, which is pronounced "da." dbang is phoneticized as Wang and dbyang is pronounced "yang."

Some examples of the correct phonetic forms of a few of the Tibetan names used frequently in this book may be found on the left side of the following list. Transliteration appears on the right.

However, in the present modified version of the Hopkins system, macrons indicating high tones will not appear in the text. In deference to common usage, a few further deviations from the system are allowed: the title Geshe (which would be Ge-shay), the names Tsong-ka-pa (which would be Dzong-ka-ba), and Lhasa (which is pronounced Hla-sa); also, the names of Tibetans who have lived in the West which are spelled as they are spelled by those Tibetans.

SCOPE

When I met with the Dalai Lama at his residence in September of 1984, I described to him the scope of the research that has resulted in this work. His response was to point out that there would be enormous value in a broader comparative study of the two truths as they are treated in the four orders (chos lugs) of Tibetan Buddhism (i.e., Ge-luk, Sa-gya, Nying-ma, and Ga-gyu). He also suggested that it would be profoundly helpful to study the relationship between the meanings of the two truths in tantric systems vis-a-vis non-tantric systems. In fact, I had originally planned this work along those very lines; I still think such a book should and will be written. Perhaps this study of the Ge-luk (dge lugs) treatment of the two truths in the Madhyamika phase of their monastic curriculum will be part of the foundation for a more encompassing understanding of the two truths in Tibetan Buddhism.

Systematic consideration of the extrinsic adequacy of the Ge-luk system also falls beyond the scope of this study. That is, while sometimes touching on these issues, my primary concerns here include neither the question, "Are the Ge-luk-bas right about what the Indian sources mean?" nor the question, "Is the Ge-luk rendering of Madhyamika cogent in the context of contemporary philosophy?" Elizabeth Napper and Jeffrey Hopkins have given us a starting point for study of the former question, while Georges Dreyfus and Robert Thurman are among the many scholars working on the latter problem.'

This work instead focuses on the internal workings of the Ge-luk reading of the two truths doctrine in Prasangika-Madhyamika. What textual or doctrinal problems does it solve for those who adopt it? How does it generate in its advocates a sense of a rationally coherent and well-ordered Buddhist world? Where are the fault-lines in the system and how are they handled by successive generations of Ge-luk-ba authors? By probing these questions, we will show how the Ge-luk philosophical treatment of the two truths works as part of a religious system.

THE TWO TRUTHS

Nagarjuna argued that the meaning of Buddha's teaching of emptiness (stong pa nyid, sunyata) as ultimate truth (don dam bden pa, paramarthasatya) is that when one analytically searches for phenomena that have been assumed to exist, they cannot be found. Nagarjuna's commentators, Buddhapalita (c.470-540?) and Candrakirti (seventh century), elaborated what came to be regarded as the Prasatigika branch of Madhyamika, holding that there is nothing that inherently exists even in a conventional sense. Tsong-kapa Lo-sang-drak-ba (tsong kha pa blo bzang grags pa, 1357-1419), founder of the Ge-luk-ba order, wrote extensively on Prasatigika- Madhyamika, asserting that Candrakirti's radical negation of inherent existence even conventionally is compatible with the mere existence of validly established phenomena. Jam-yang-shay-ba (jam dbyang bzhad pa, 1648-1721), Jay-dzun Cho-gyi-gyel-tsen (ije brtsun chos kyi rgyal mtshan, 1469-1546), Pam-chen So-nam-drak-ba (pan chen bsod nams grags pa, 1478-1554) and others composed textbooks (yig cha) on Madhyamika, interpreting and analyzing Tsong-ka-pa's view in a format conditioned by the pedagogical requirements of the Ge-luk-ba monastic colleges (grwa tshang). These textbooks are primarily based on Tsong-ka-pa's Illumination of the Thought, which is a commentary on Candrakirti's Supplement to (Nagarjuna's) "Treatise on the Middle Way" (Madhyamakavatara).

Ge-luk-bas rank Prasangika-Madhyamika as the most profound of all thought-systems, and Nagarjuna (second century), the founder of Madhyamika, unequivocally declares the importance of the two truths in his Treatise on the Middle Way:2

Doctrines taught by the Buddha Rely wholly on the two truths: Worldly concealer-truths And truths that are ultimate.

An ultimate truth is an emptiness-that is, an absence of inherent existence (rang bzhin gyis grub pa, svabhavasiddha). Concealer-truths (kun rdzob bden pa, samvrtisatya) are the bases of emptinessesthat is, the phenomena that have the quality of being devoid of inherent existence.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism)»

Look at similar books to The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Two Truths (Studies in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.