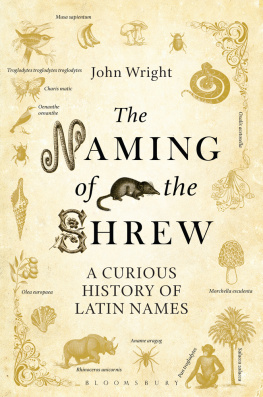

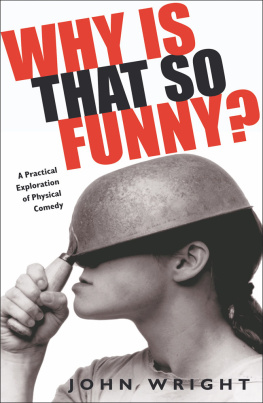

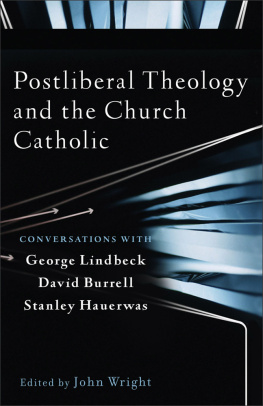

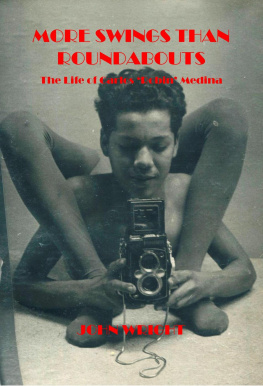

THE FORAGERS CALENDAR

THE FORAGERS CALENDAR

A Seasonal Guide to Natures Wild Harvests

JOHN WRIGHT

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

Profile Books Ltd

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright John Wright, 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Photos on pp. Bryan Edwards.

All other photos John Wright.

Design by James Alexander/www.jadedesign.co.uk

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78125 6213

eISBN 978 1 78283 2386

For Martin, my dear friend from Sleepy Valley

CONTENTS

NOTE TO THE READER

Eating wild plants, fungi, seaweeds and animals is not without its perils. Accurate identification is essential, and nothing should be eaten unless you are certain of its identity and thus edibility. This book provides sufficient information to identify all of the species mentioned, with the more difficult species described in appropriately more detail. It is not, however, a book designed primarily for identification purposes, so it is often worth checking with a further source.

Wild foods are often unfamiliar foods with the potential to disagree with individual metabolisms. This is particularly true of fungi. When eating something new, it is always worth consuming a small amount first to see if you like it and it likes you.

Some wild foods are not suitable for people suffering various infirmities and some are not suitable for expectant or nursing mothers. Advice on these is provided within the text.

Always collect from clean environments and always wash plants and seaweeds.

Most species of fungi are best cooked, and some are moderately poisonous if eaten raw.

While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained within this book, in no circumstance can the author or publisher accept any legal responsibility or liability for any loss or damage (including damage to property and/or personal injury) arising from any error in or omission from the information contained in this book, or from the failure of the reader to properly and accurately follow the instructions contained in this book.

INTRODUCTION

At some point during September my father would announce that it was time to pick blackberries. Everyone would move instantly into action. Mother unearthed baskets, and a couple of hooked walking sticks were recovered from the aromatic cupboard under the stairs. Sandwiches were made, and a flask of tea prepared. My young sister was dragged away from her game of Cindy Buys a New Dress and bundled into my fathers 1928 Morris. By the 1960s the Morris was already sufficiently venerable to cause comment. We loved it and called it The Bus, and it ferried us over Portsdown Hill from our Portsmouth home to the glorious wilds of rural Hampshire. Those days were prickly, messy and sweet, and I loved them.

Our other family passion was to go cockle-hunting in Langstone Harbour, to the east of Portsmouth, plunging our hands in the sticky mud to find our prize. That too was a joy, though I thought cockles much inferior to blackberries as a food.

Just childhood memories, of course, but it was only recently that I began to view them in their true light. Those days were the best of my childhood because, unlike television and school, they felt completely real.

Hunters and gatherers. That is what we are, and nature rewards us, not just in the food these pursuits provide but also in the more fundamental form of rewarding our souls. On those blackberry-picking expeditions I was doing what I was meant to do, and it felt so right.

The modern world views hunting as barbaric and gathering as an absurd affectation, at best, and a damaging imposition on the natural world, at worst. But searching out our food is completely natural, with a history going back to the first animals. What it is not is a fad or, worse still, a middle-class fad. For our recent ancestors, and even in living memory, foraging was the natural and obvious way to obtain food. Now the obvious thing to do is go to the supermarket or order a takeaway. In this we have lost so much, and food is merely pleasant fuel, a commodity. When we forage, we truly know the organism we choose to collect, its mode of life, its beauty, its value and its season, and in a way unobtainable from food that is bought, we feel we deserve it, we own it.

I have led around seven hundred forays over the last quarter of a century, showing people how to salt for razor clams, catch brown shrimps, identify mushrooms and plants, and the joys of seaweed. People seem to enjoy our days out, often more than they think they will. I take no great credit for this; all I do is explain things and, above all, slow my companions down. On seeing the abundance of mushrooms, or the wild extravagance of berries, a frequent comment is, Have you brought me to a special place? The answer is that, yes, it is a good place, though much like many others. The difference is that today I have given them time to look.

Searching for wild food has a powerful effect on how people see the natural world. They suddenly find themselves a part of it, rather than merely an onlooker. Authorities and landowners do us all a disservice by making us keep off the grass, and the many excellent television programmes on natural history leave us in no doubt that they are showing a world beyond our horizons, not a world to which we belong.

Foraging immerses us in the world, and we come to know it, love it and seek to protect it. We see things we have not seen before or even imagined, such as the spectacular gall known as Robins Pincushion or the bright orange of a rust fungus on a leaf. I know that I have succeeded on one of my forays when I hear someone say, A walk will never be the same again! My aim in this book is not just to show you how and when to find free, wild food, but also to encourage you during your expeditions to view the natural world around us as more than a painted backdrop to our lives, and as something exquisite in its detail.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

This book is in the form of a month-by-month account of what can be found when. I knew this to be a task of compromise and difficulty long before I put pen to paper. Nature has its own ideas of when things should appear, and even of whether they will appear at all. I have found Horse Mushrooms in April and Wood Blewits in June, both species half a year too early (or too late). But there is some pattern, and it is recorded here to the best of my ability and that of those naturalists and foragers I have consulted.

Most wild foods are available for more than a single month. At the back of the book you will find a calendar which lists all the wild foods mentioned in the text, placed in the months in which they might be found and with an indication of when is their main season. This information can also be found within each monthly chapter.

I have placed all the main species descriptions in the first month that their flowers, fruit, etc. are likely to be available in good quantity and condition the most reliable month, to put it another way. Some species produce more than one edible item. The Elder, for example, provides flowers in June (and late May and much of July) and berries in August and early September. So the description of the Elder, its flowers and its berries is provided in the June chapter. In August and September the berries will be listed at the beginning of the chapters as available, and you can check back in June to find a more detailed description of the plant.

Next page