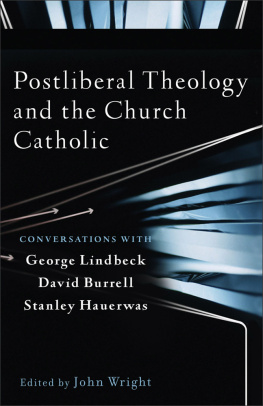

2012 by John Wright

Published by Baker Academic

a division of Baker Publishing Group

P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287

www.bakeracademic.com

Ebook edition created 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meansfor example, electronic, photocopy, recordingwithout the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

eISBN 978-1-4412-3636-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

To

Reverend Katherine S. Wright

Chair of the Multi-Congregational Board,

The Church of the Nazarene in Mid-City, San Diego

Contents

Acknowledgments

In the late winter of 1984, Robert Louis Wilken, the professor in my first Christianity and Judaism in Antiquity PhD seminar at the University of Notre Dame, pressed into my hand a newly published volume called The Nature of Doctrine: Religion and Theology in a Postliberal Age . I had never heard of the author, a Yale Divinity School professor named George Lindbeck. I finished the book that night. Perhaps this book began there.

In the summer of 1984 I ran into Stanley Hauerwas at the second-floor copier in the Hesburgh Library at the University of Notre Dame. The next day he was to leave South Bend to begin his teaching post at Duke Divinity School. He kindly greeted me and I thanked him for his work, told him that I mourned never being able to study under him in class, and wished him well from one Wesleyan to another. Perhaps this book began there.

In the spring of 1991 I shared lunch with David Burrell when I served as a visiting professor teaching general education students at the University of Notre Dame. In the middle of the lunch, David spoke about his relationship with George Lindbeck when Burrell was chair of the Department of Theology at Notre Dame. Perhaps this book began there.

To speak of the beginnings of a book is to recognize how indebted ones life is to the gift God gives to us in others. Acknowledgments remind us that none of our work is really our own, particularly one like this book. First, I need to thank George Lindbeck, David Burrell, and Stanley Hauerwas for their graciousness as they gathered for a conversation in the winter of 2007 in Kansas City, Missouri. While I had known David and Stanley when sojourning at the University of Notre Dame, I had never formally been their student; I had never even spoken to Professor Lindbeck until I called him in his retirement to inquire about his interest in taking part in a conversation with David and Stanley. Yet all three agreed to come to engage in these conversations only upon my request. Ron Benefiel, then president of Nazarene Theological Seminary, offered to sponsor the conversation that took place under the Hugh C. Benner endowed lectureship in memory of Hugh C. Benner, the founding president of NTS. Ironically, a Benner scholarship had helped pay for my undergraduate education at Mount Vernon Nazarene College. It was an honor to have the late Dr. Benners daughter, Janet Miller, his son, Dr. Richard Benner, and his daughter-in-law, Dr. Patricia Benner, in attendance for the conversations.

Dr. John Hawthorne, then provost at Point Loma Nazarene University, provided early encouragement for the project, and later, paid travel expenses out of the Provosts Fund at PLNU for my participation in it. Monsignor Lorenzo Albacete of Communion and Liberation discussed the project with me in its early stages and enthusiastically embraced it. Monsignor Albacete was to interview Drs. Lindbeck, Hauerwas, and Burrell. Unfortunately he became ill immediately before the event and was unable to attend. I was required to stand in for him. Dr. Andy Johnson, professor of New Testament at Nazarene Theological Seminary, did the unrecognized work, for which I am thankful, in overseeing the local logistics for the entire event.

It has taken me too long to turn these interviews into this book. Perhaps it never would have been completed without a sabbatical granted by my institution, Point Loma Nazarene University. Jason Byassee, who attended the conversation, provided early encouragement to record the conversations in book form. Rodney Clapp guided the work through the contractual and editorial processes at Baker Academic and provided wise editorial suggestions. Professor Hauerwas read drafts of the chapters and provided encouragement and feedback. Dr. Mark Mann, director of the Wesleyan Center at Point Loma Nazarene University, provided keen eyes for reading portions of early drafts of the book, as did my young friend Professor Jonathan Tran of Baylor University. He is a much better judge of my writing than of NBA players. My wife, Rev. Kathy Wright, provided help in transcribing the oral conversations from NTS into typed prose, as did my daughter, Natasha Wright. To share in this project with them and my sons, Johnny, Carl, and Tony, has been a deep joy.

The book is dedicated to my wife of over thirty-one years, Rev. Kathy Wright. She has unswervingly supported me in this book as throughout all life. When she proclaims the Word of God in her preaching at the Church of the Nazarene in Mid-City, California, she helps me see why such a project is important. When she oversees pastors working harmoniously together in one building for seven different congregations from various regions throughout the world in a strange place called San Diego, she helps make this work intelligible. For her witness and her help in this project, all I can do is give God thanks.

John W. Wright

Trinity Sunday, 2011

If modern philosophy can be seen as post-medieval, then post-modern philosophy will have to be read as post (post-medieval).

David Burrell

It is hard enough to understand the past, let alone predict the future. Who in the middle of the 1980s predicted the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1989? Looking back on the series of economic bubbles in the past twenty years, we now wonder why mainstream economists did not see the housing bubble that formed in the early 2000s. This inability to see what seems evident in retrospect has led to economic chaos throughout the world. It seems safe to say that unexpected, utterly contingent History, like life, is full of surprises.

Interpreted from within the history of a visible church catholic, the twentieth century proved both horribly grievous and delightfully surprising. The sufferings of the first half of the century paved the way for healing a thousand years of increased fragmentation in the ecclesial body of Christ. Yet the later part of the century witnessed new fissures in the church, even as God changed its social location from its medieval European centers to the Southern hemisphere and Asia.

It seems almost bizarre today to raise the question of the visible unity of the church. Rifts within the church throughout history appear too deep, and the truthfulness of theological claims seems unintelligible when analyzed solely in light of the immanent working of power in history. The question of the visible unity of the church in faith and order seems at best nostalgic, and at worst reactionary and oppressive. Theological discourse in the West has tended to emphasize vague humanistic ethical goods like freedom or justice; it has also sought to develop a marketable group-identity for self-identification, meaning, and proselytism. Denominations seem natural, so natural that even those within the Roman Catholic Church can call themselves part of a denomination.

Next page