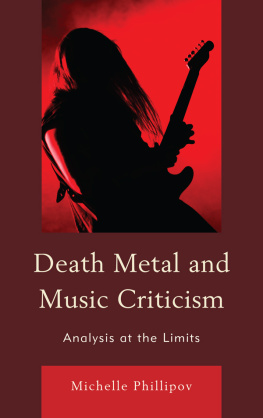

Mysticism, Ritual and Religion in Drone Metal

Bloomsbury Studies in Religion and Popular Music

Series editor: Christopher Partridge

Religions relationship to popular music has ranged from opposition to the Devils music to an embracing of modern styles and subcultures in order to communicate its ideas and defend its values. Similarly, from jazz to reggae, gospel to heavy metal, and bhangra to qawwali, there are few genres of contemporary popular music that have not dealt with ideas and themes related to religion, spiritual and the paranormal. Whether we think of Satanism or Sufism, the liberal use of drugs or disciplined abstinence, the history of the quest for transcendence within popular music and its subcultures raises important issues for anyone interested in contemporary religion, culture and society. Bloomsbury Studies in Religion and Popular Music is a multi-disciplinary series that aims to contribute to a comprehensive understanding of these issues and the relationships between religion and popular music.

Christian Metal, Marcus Moberg

Mortality and Music, Christopher Partridge

Religion in Hip Hop, edited by Monica R. Miller, Anthony B. Pinn and Bernard Bun B Freeman

Sacred and Secular Musics, Virinda Kalra

Mysticism, Ritual and Religion in Drone Metal

Owen Coggins

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Contents

First, thanks go to all the participants in this research, particularly those who gave their time and personal insights to this project. This includes everyone who completed surveys, whose words I read online, who hung out with me at drone metal shows and music festivals, whose music I enjoyed and endured, and particularly those who agreed to be interviewed. Thank you for sharing with me your experiences and reports of musical experience, which were frequently brilliant, funny, absurd and profound.

Much gratitude is due to Paul-Franois Tremlett, Byron Dueck and Graham Harvey, whose wise and generous guidance made this project possible, and to all those who have offered their comments on this research as it developed.

Finally, thank you to my family, especially my partner Caitlin, who has been endlessly supportive and who I love very much. Her proofreading work was also invaluable.

This book is dedicated to my parents, to whom I owe so much.

Introduction

On a Thursday evening at the Brudenell Social Club in Leeds, a crowd of around three hundred people fall silent at the heavily amplified sound of a recorded Arabic prayer that is broadcast to Muslim pilgrims as they approach Mecca. Two men in different parts of the crowd join in with the prayer, having learnt each syllable by sound from repeatedly listening to a recording which includes the same prayer. After about a minute, a heavy solo bass guitar line enters, rumbling through a sequence which falls upon an extended note that is emphasized by the downbeat. That same riff cycles three more times, before snare roll and cymbal are added, inviting heads to nod while chests vibrate with the bass. Several minutes in, the first line of lyrics is introduced; the cryptic phrase Walk Melchizedek shrine descender is recited and then left to reverberate over further repetitions. Around thirty minutes later, people stand without talking, many with eyes closed and heads bowed, listening to a high-pitched vocal wail over the top of a recording of a chanted Sanskrit mantra. Another half hour into the drone metal performance, another monotonously repeated bass note holds sonic tension through a period of comparative quiet, until the bass player intones the single word Lazarus. A final five-minute explosion of heavily distorted bass riffs and clattering drums then erupts over raised hands, bobbing heads, and bodies absorbed in slow, repetitive, vibrating noise. Before dispersing or getting a final drink while the bar is still open, several attendees crowd round a table at the back of the room to buy vinyl records adorned with artwork displaying angels, a Byzantine icon of John the Baptist and names or phrases such as God Is Good, Pilgrimage and Conference of the Birds (the latter a classical Persian Sufi allegory). Others pick up black T-shirts, similar to many other black heavy metal band shirts worn by attendees, these ones emblazoned with a single word, the name of the band that has just performed Om.

was reminded of the atmosphere he had experienced at prayer meetings. He was, however, also careful to distinguish this from his experiences of the Holy Spirit:

Seeing Om live you get the same kind of atmosphere as what you get with a church or religious service. [But] really strong experiences that you have that you would say are definitely from God would be qualitatively different. (O69, Interview, 2013)

Another Om listener in Germany who attended a concert on the same tour described how Oms constant level of sonic intensity was meditative and calming, also mentioning connections with yoga, mantras and Gregorian chant as well as ideas of travel. Intrigued by her own response to the music, and witnessing other people appearing to be entranced at the show, she described herself as not religious but interested in the spirituality in drone metal music. This occasioned recollection of being fascinated as a child at peoples behaviour at a church service (O21, Interview, 2014). As reviewers of Oms 2012 album Advaitic Songs put it, drone metal can be pan-global mystical music for the heavy-metal demographic (Powell 2012), interfaith heaviness (Dronelove 2012), or as close to a religious experience as anyone will get within the extreme music community (Hemy 2012). Drone metal music pushes the limits of heavy metals sonic conventions, tests the endurance of listeners and invites descriptions which employ a vocabulary of religious experience, ritual and mysticism. In examining sound, symbols and description in and around musical experience, this book traces the production of this mystical discourse in drone metal culture.

Drone metals mystical sound and discourse

Drone metal is a marginal and largely underground subgenre of heavy metal music, first emerging in the early 1990s and having developed significantly since or musical development), overwhelming volume, amplification and distortion, and extension radically beyond popular music conventions. Sounds, symbols, images and vocabulary associated with a range of religious, ritual, spiritual and mystical practices and concepts are frequently incorporated into performances and recordings by Om and other drone metal musicians, and are prevalent in listeners communication about this music.

The musical culture of drone metal incorporates practices, experiences and uses of language understood by diverse audiences to be related to religion, spirituality or mysticism. In this book I present the results of five years of ethnographic research from 2012 to 2017 exploring the language of mysticism, spirituality and religious experience in drone metal music culture. In existing academic literature, drone metal has been occasionally discussed, sometimes in relation to reception and usually comprising anecdotal reports of concerts by the band SunnO))), where ritual or transcendence are often mentioned.

Fieldwork and mixed methods

Ethnographic methods have been used in several studies to examine other intersections between religion and metal. Religion is understood as inspiration or foil for lyrics or musicians ideologies (Cordero 2009, Baddeley 2010, Granholm 2011), as a normative framework of public morality (Wallach 2008, Hecker 2012) or as a more or less stable social institution within or against which metal music situates itself (Moberg 2009). Less often has religion in metal been addressed as a communicative resource, offering potential vocabularies or ways of speaking for listeners as well as musicians. Studies that have attempted to account for such productive uses of religious symbols have surveyed different positions on metals potential influence on religiosity (Hjelm 2015) or used textual Biblical criticism to understand explicitly anti-Christian bands as engaged in practicing theological exegesis (Naylor Davis 2015). In this book, by preparing an empirically grounded methodology for studying mysticism in popular music culture, I make space for a reading of religious symbols and ideas as used by listeners, ethnographically examining these uses in context within a wider extreme metal milieu.